Pacific Northwest Ballet / Joyce Theater, NYC / January 5-10, 2010

Pacific Northwest Ballet, based in Seattle, is making its first New York appearance in 13 years with a program of four ballets, three of them new to our town. The more substantial of them are Twyla Tharp’s Opus 111 and Benjamin Millepied’s 3 Movements. Astonishingly, not a one is by George Balanchine, whose works have long been the most significant part of the troupe’s astutely chosen repertory.

Founded in 1972, PNB was subsequently led for nearly three decades by the husband-and-wife team Kent Stowell and Francia Russell (he got top billing, but she’s the most famous); earlier, both made their performing careers with the New York City Ballet. Russell took charge of PNB’S ever-growing Balanchine acquisitions. Her productions, known to East Coast ballet fans largely by hearsay, were praised for their accurate rendering of the choreography. I saw a couple of them and found them rather dry and dull–the work of a devoted accountant.

Peter Boal, celebrated for the purity of his dancing as a principal with the City Ballet, took over from Stowell and Russell in 2005. You’d think he’d be the first to include Balanchine in an engagement taking place on Balanchine’s “home turf”–if only to show the competition how well, how distinctively his company dances the master’s creations. Just last year, Miami City Ballet, directed by another important NYCB alumnus, Edward Villella, did just this–thrillingly.

Perhaps Boal was more interested in showing the Tharp and the Millepied works because he commissioned them for the company–both in 2008.

Pacific Northwest Ballet in Twyla Tharp’s Opus 111

Photo: Angela Sterling

Tharp’s Opus111, named for the Brahms string quintet to which it’s set, is easily the best dance on the program. With its cast of twelve, it shows off the soft grace of the PNB dancers and rarely hints at the punitive physical extremes that have been typical of Tharp’s major works for years now and the way-cool slouchiness that so disgruntled old-school observers of her early masterworks. Yes, the choreography abounds in Tharp’s daredevil lifts and maverick twists of the classical ballet vocabulary, but these elements have been gentled–either by Tharp herself or by the way the PNB dancers perform them–and no longer come across as brash challenges to officialdom.

The main characteristic of Opus111, though, is a complex braininess that has been typical of Tharp from Day One. You can hardly parse it on a first viewing, though you can sense that it underpins the ballet’s structure. Here, the choreographer revels in mirror-imaging of all sorts and related complementary juxtapositions, as demonstrated in the lyrical second movement, where the dancing of the main couple is suavely accompanied by, or set off against, the movement of two auxiliary trios and, if I remember rightly, another pair. Tharp operates so smoothly here, she made me think of the secondary groups as the principals’ landscape.

The women in the piece wear soft slippers rather than pointe shoes, ballet’s traditional way of indicating that they are people of the earth, not members of the aristocracy. And folk motifs, which occur briefly and subtly throughout the piece (echoing qualities in the music), emerge full-force in the finale, where every foot is robustly flexed–as classical ballet imagines peasant-dance style–and with the performers arranged downstage in two parallel lines that stretch from one side of the proscenium arch to the other, presenting themselves guilelessly–fresh-faced, forthright, and smiling.

Opus 111 isn’t likely to be considered a landmark in Tharp’s career, but for me it saved the evening.

I don’t know what to make of Benjamin Millepied–a City Ballet principal–as a choreographer. Ambitious and diligent, he “improves” doggedly, learning how to bring off one basic task of choreography after another. But he hasn’t yet made me want to see one of his dances a second time. Au contraire.

Pacific Northwest Ballet in Benjamin Millepied’s 3 Movements

Photo: Angela Sterling

Of late he’s been teaching himself to manipulate large numbers of dancers effectively. Earlier, I saw another of his exercises in this vein that resulted in a frantic, blurry mess, like rush hour at Times Square. But 3 Movements, set to Steve Reich’s relentless Three Movements for Orchestra and featured as the second “big number” on the Joyce program, was as clear as could be; indeed it looked as if most of it had been designed on graph paper. Like all the Millepied’s works I’ve seen, this one seems hollow in the sense of having no interior life, no imaginative vision, no notion of what makes a ballet unforgettable. The answer lies beyond the realm of efficiency.

The Joyce program is completed by a pair of smaller pieces, no doubt audience pleasers though hardly distinguished works of art. Edwaard Liang’s Für Aline, a duet created in 2006, is set to a radically sparse score–single notes separated by silence, constituting a fragment of melody that haunts the memory–by the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, a favorite among dance makers with a melancholy bent.

Liang gives us a young man apparently unable to relinquish his obsessive memory of the woman he loved, who has died. For him, she exists in the present–as exquisite and delicate as ever, moving with a “being beauteous” quality. Unfortunately, Liang depends on bits and pieces he’s (and we’ve) seen and liked in other, better, choreographers’ work, without giving them a meaningful new context and seems devoid of invention when left to the his own devices. What’s more, the mood of his piece is woefully sappy. Still I did appreciate the moment in which the lost beloved suggests that she–though presumably now dwelling in the Elysian Fields–misses her partner as much as he misses her.

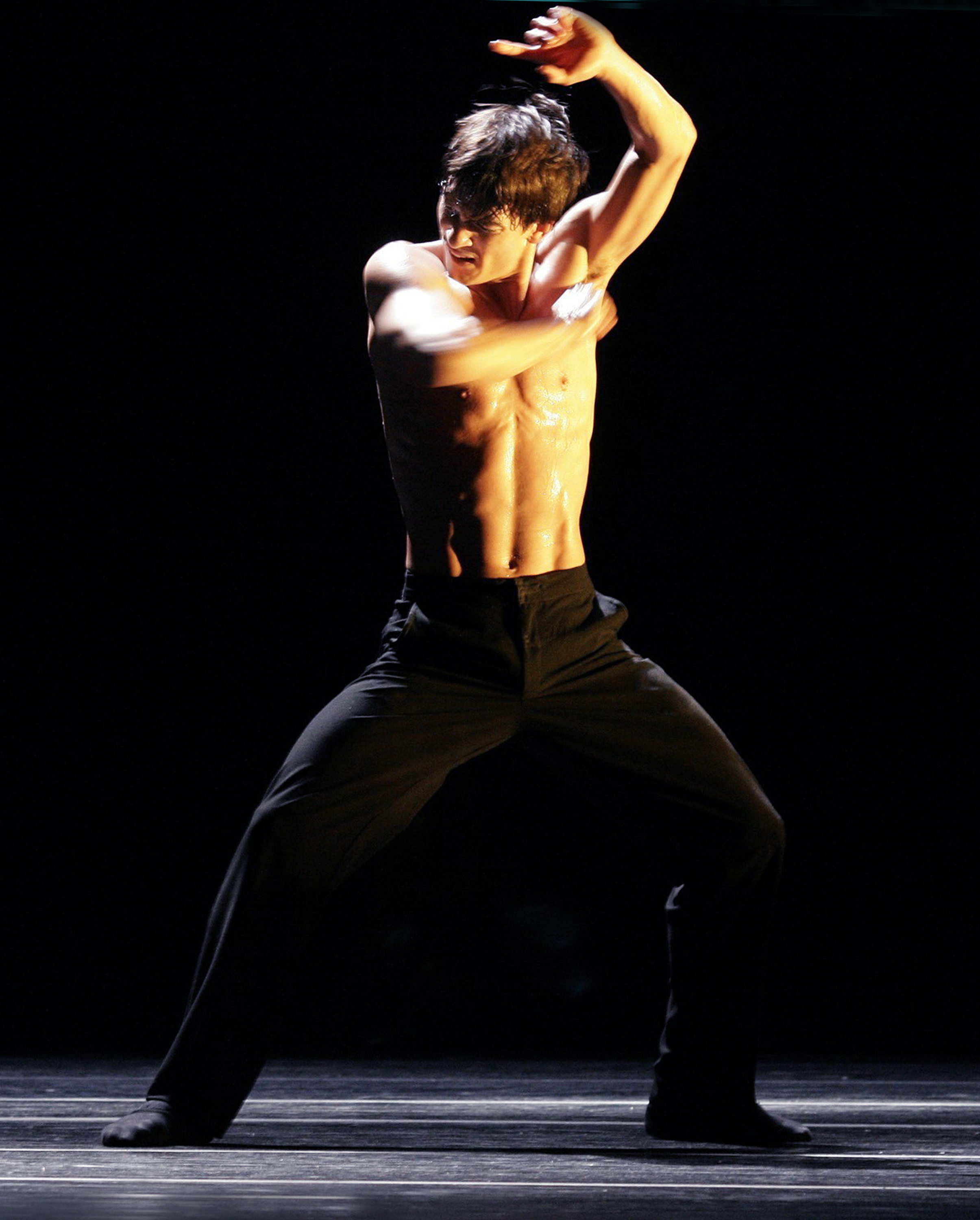

Pacific Northwest Ballet in Marco Goecke’s Mopey

Photo: Chris Bennion

Marco Goecke’s 2004 male solo, Mopey, is set to music by C.P.E. Bach, then the theatrical ploy of no sound at all, then to raucous sound from The Cramps. It describes an alienated youth who suffers, violently and picturesquely, from (a) drug addiction; (b) spasmodic hyperactivity caused by Attention Deficit Disorder; (c) an unspecified form of psychosis. Choose one or all of the above. Because of its length, perhaps, and its physical challenges (sheer endurance being just one them), it’s made to impress but not, unfortunately, to express anything beneath the surface.

Given the dubious worth of these two pieces, Boal surely would have done better to replace them with–if not a Balanchine contribution–at least one of the several works of Jerome Robbins that he has acquired for PNB in the course of his tenure.

As for PNB’s dancers, they make a very good ensemble, but even the best among them, charged with leading roles, lack the ability to thrill your eyes and heart, to “own” the stage as real stars do. This capacity may come with time, but then a lot of time has already passed.

What really broke my heart was the sight of Carla Körbes, justly adored by the New York audience when she was with City Ballet, although she never received the roles her ballerina-qualities seemed to deserve. Now a principal with PNB and dancing leads in three of the opening-night ballets at the Joyce, she looked hampered both by embonpoint and, far more telling, a failure of desire.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias

I’m grateful for the meticulous description of the four works on PNB’s Joyce Theater program, although one of them is not new to New York [I’ve corrected the error in my text. TT], or to that theater if it comes to that–Boal commissioned “Mopey” for his little pick-up company before he took the position of artistic director at PNB. I hated it then, and have felt no desire to see it again.

And I think I must take humble issue with TT’s assessment of Russell’s staging of the Balanchine rep. Certainly it is extremely meticulous and careful–another critic has described it as “schoolmistressy,” and it can come across as very dry when not danced in Seattle, because the dancers, at least for PNB’s 1996 City Center season, were extremely nervous. A couple of years ago, however, Russell staged “Apollo” on Oregon Ballet Theatre, working with young and inexperienced dancers (as well as experienced ones) and it was gorgeous, juicy, full of youth and conviction, particularly in the performance of Adrian Fry as Apollo. This was, I might add, the “long” version of the ballet, showing the birth of Apollo, his first baby steps, etc.

I don’t know why Boal didn’t program any Balanchine at the Joyce, but I would venture to guess that he’s wanting to show his own stamp on the PNB rep, which for good or ill is very different indeed from Stowell and Russell’s. They are a damned hard act to follow.

I wish I had seen the performance, but I did not. I’m only expressing gratefulness for commentary that is clear, to the point, and, most of all, has something insightful to add to the discussion. Onward, please.