New York City Ballet / David H. Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 24, 2009 – February 28, 2010

This story has a back story. Let me whisk you through it.

Some two years before the New York City Ballet danced the January 21st world premiere of Alexey Miroshnichenko’s The Lady with the Little Dog, negotiations had broken down between Peter Martins, who directs the company, and Alexei Ratmansky, then head of the Bolshoi Ballet in his native Russia. They’d been discussing the possibility of Ratmansky’s becoming the City Ballet’s Resident Choreographer. (The job had been created a decade ago for Christopher Wheeldon, who, having formed his own small, ambitious company in 2007, subsequently wanted to give it his full attention.) Shortly after Ratmansky’s negotiations with City Ballet collapsed, he was snapped up by American Ballet Theatre.

Ratmansky was obviously a catch–he and Wheeldon are widely considered to be by far the most gifted choreographers in classical dance today–and balletomanes entertained the foolish hope that he would prove to be “another Balanchine.” Of course he wasn’t, but observers were consoled by his abundant gifts: a dance vocabulary that is inventive yet firmly rooted in traditional classical technique; the wit and human warmth of his creations; his respect for (and delight in) the past and his ability to make it new.

When City Ballet announced that this season would see a new ballet commissioned from another Russian, Alexey Miroshnichenko, hopes were more modest, but still unrealistic–that Miroshnichenko would at least prove to be “another Ratmansky.” No such luck.

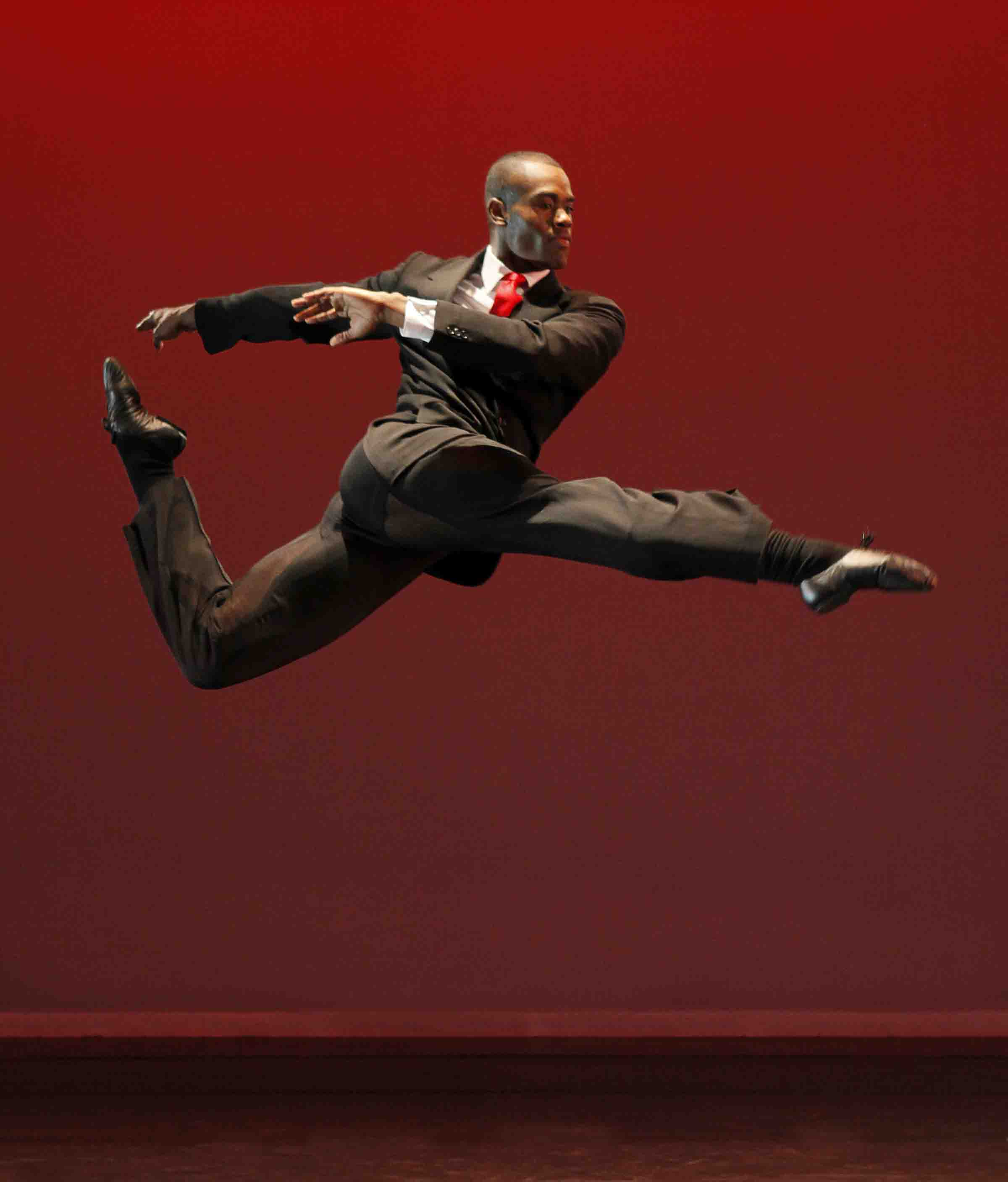

Sterling Hyltin and Andrew Veyette in Alexey Miroshnichenko’s The Lady with the Little Dog

Photo © Paul Kolnik

The Lady with the Little Dog is, at best, a sweet Valentine of a ballet–pretty and charming, but without much significance. It was inspired by Chekhov’s poignant, similarly titled story in which a man and a woman, each leaving a disappointing spouse behind, visit a seaside resort, ripe, for different reasons, for a passing affair. He’s an aging playboy; she’s a delicate young thing who craves more from life than a marriage that starves her imagination. Instead they find a fierce attachment (call it love) they can’t escape.

Miroshnichenko adopts the names Chekhov used for his main characters, Anna Sergeevna and Dmitri Dmitrievitch, but keeps the proceedings semi-abstract. Sterling Hyltin as Anna has the youth and delicate beauty of the young woman’s Chekhovian ancestor, but Andrew Veyette, as Dmitri, is merely a generic attractive young man, as caring and tender as a romantic heroine might wish and a swell dancer to boot.

Boy meets girl when Anna is out walking her fluffy little dog. They are attended by a male octet in short-sleeved gray unitards. The house program calls them Angels, but their movements are often those of adorable puppies. The cuteness factor is not as unbearable as you’d think, but it–and the central part these fellows play in guiding the couple’s encounters, even to simulated nudity and intercourse–is enough to remove the ballet decisively from the Chekhovian realm of small truths that, accumulating quietly and inexorably, end by piercing the heart.

The most disheartening part of Miroshnichenko’s effort, though, is its lack of interest and invention sheerly as dance. To be sure there are two big pas de deux–obvious choreographic challenges–but the results are invariably banal. In the falling-in-love duet Veyette lifts and turns Hyltin so that her legs swirl out into space, in the familiar way of ice-dancing couples, This “floating on air” is a metaphor for love’s ecstasy, but it has become a cliché and Miroshnichenko’s bag of tricks is far too full of them.

The score, by the Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin (the husband of the celebrated ballerina Maya Plisetskaya, to whom the ballet is dedicated), couldn’t suit the piece better, being as delicate and sweet as a meringue and equally devoid of substance. Philipp Dontsov’s scenery is spare, essentially a gauzy front cloth that lifts up and a backdrop that stays put, both broken by pale rectangles, as if to indicate modernity. For variety’s sake, the upstage drop is subjected to mood lighting by the City Ballet’s Mark Stanley. One can justly accuse Stanley of making most ballets too dim, but he is not often given to the trite ploy of using rhubarb red to indicate erotic passion.

To my mind, the only worthy aspect of The Lady with the Little Dog is its serving as a vehicle for Hyltin, extending her beyond her crisp technique to create a character who is well-nigh irresistible. As I knew you’d want to know, the pale, fleecy scrap of a live lap dog that she walks at the ballet’s opening is the dancer’s very own, and the vibes between them are indeed delectable.

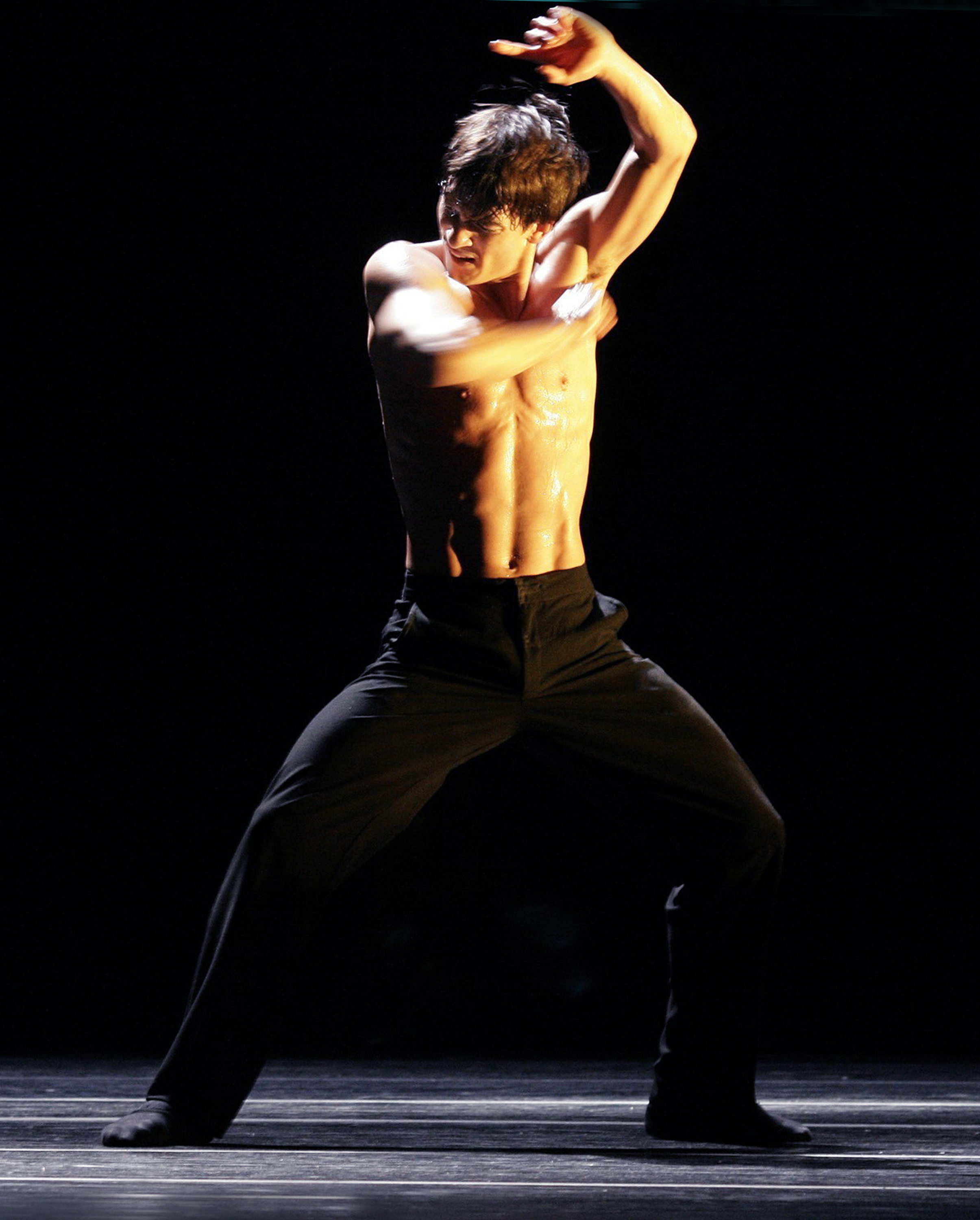

Dancers of the New York City Ballet in Peter Martins’s Naïve and Sentimental Music

Photo © Paul Kolnik

Peter Martins’s latest ballet, Naïve and Sentimental Music, to the John Adams score from which it takes its name, had its premiere on November 24, 2009, for the gala opening of the City Ballet’s season. And it was likely that the choreographer had the grand gesture in mind when he cast nearly all of the company’s principal dancers in it. Of the cast’s 26 performers, only one, Adrian Danchig-Waring, was still “just” a soloist, but he’s clearly headed for the top category and entirely deserving of it.

Unhappily, the grand gesture did little to make Martins’s ballet memorable. Yes, it was impeccably performed, yet the choreography adamantly refused to reveal the individual distinctiveness that had made each member of this top-of-the-crop group worthy of the ranking. For Martins, it seemed, the strong, clear technique that almost all of them displayed was sufficient in itself. Is he immune to the love that can be inspired by the particular dancing temperament of an individual artist?

For the record: The piece comprises three sections. The first is the most highly populated, with seven couples elaborating, in different groupings, on Yvonne Borree’s opening statement of unfurling a leg now to the front, now to the back. The simple movement develops into many a speedy challenge until the stage looks charged with activity. The women–in beautiful tunics by Liliana Casabal that range through a spectrum of blues and greens–are as light and sharp-edged as a Kleenex; the men, naturally beefier, put more obvious energy into their steps. All of them perform as if “exactitude” were their mantra. But the point of their activity is either invisible or, more likely, non-existent.

The second section is devoted to adagio dancing, with its cast of three couples in pure white taking turns at being in the spotlight while the two remaining pairs do complementary slow duets at a distance in a meditative twilight. It is, as might have been expected, the women who stand out: the luscious Sara Means; Maria Kowroski, the diva of pulled-taffy dancing; and the about-to-retire Darci Kistler, who happens to be the choreographer’s wife.

As was also to be expected, the movement is abstract. And then suddenly in the final duet–for Kistler, with Stephen Hanna–the couple is interrupted by a black-clad man who steals Kistler away from her partner and proceeds to conduct her through a rendezvous with death reminiscent of, yet nowhere as powerful as, the macabre and sensuous one in Balanchine’s La Valse. Next, unfathomably, the man in black is replaced (not thwarted, simply replaced) by Hanna, and the dance returns to the ineffable rites of a gated (think heavenly) community. Are we to understand, from that brief narrative intrusion, that Kistler is undergoing a near-death experience (perhaps her retirement)? The problem here is that Martins has failed to make his intentions clear.

The third movement, also for three couples, the women costumed in gorgeous shades of red, has the kind of ferocity you’d expect if someone had yelled “Fire!” in a crowd. In response to the music, the movement now blazes, though it is always tamped down a little by Martins’s insistence on a seamless flow in the action.

To close the piece, the entire cast assembles for a geometrically ordered finale that has absolutely no dance fervor in it. I saw the ballet twice, and each time, as the curtain came down, I felt I hadn’t witnessed anything significant–or even simply entertaining.

After their respective premieres, the Martins and Miroshnichenko ballets appeared on the same program for the City Ballet’s annual New Combinations evening, which is meant to honor Balanchine’s birthday. Surely, in his lifetime, Mr. B knew one should be wary of choreographers bringing gifts.

© 2010 Tobi Tobias