Dear Readers,

I will be working in Copenhagen NOV 17 through NOV 30 and not posting on SEEING THINGS until my return. Meanwhile, please continue to send your Comments on the pieces already posted, especially recent reviews and all of the PERSONAL INDULGENCES essays; I will post your Comments as soon as I can.

tt

Archives for November 2009

Morphoses Falters

Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company / City Center, New York City / October 29 – November 1, 2009

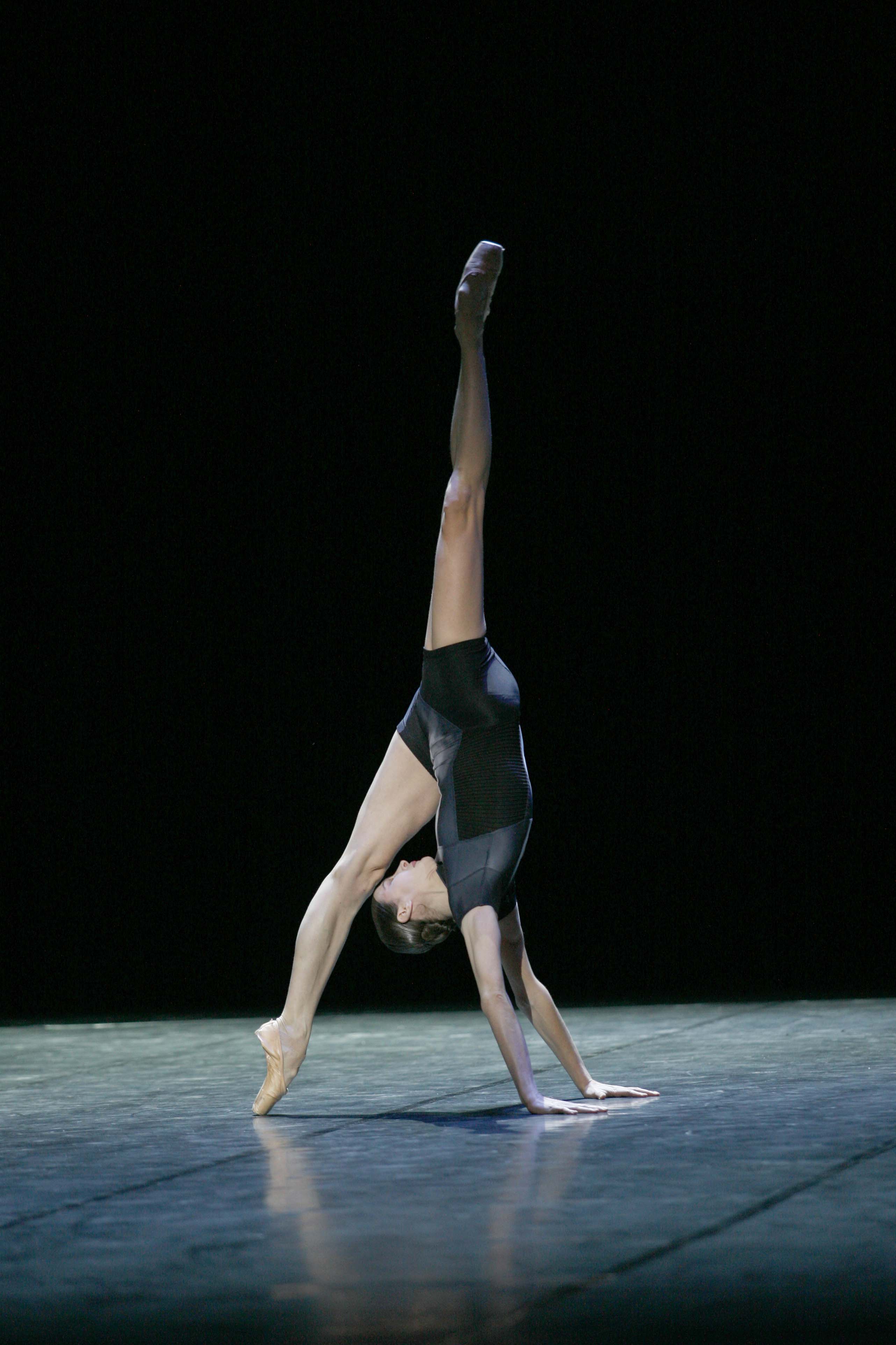

Christopher Wheeldon’s

Rhapsody Fantaisie

Photo: Erin Baiano

Three years ago, when Christopher Wheeldon left the security of his position as Resident Choreographer at the New York City Ballet to form his own small company, Morphoses, his head was full of extravagant dreams about making classical ballet new for the 21st century. He even fulfilled some of them. But the economic downturn has thwarted his progress. Ballet companies, no matter how modest in scale, cost major money, and donors are feeling poor these days. Which brings us to the nagging question of whether or not Morphoses is really worth saving–at all costs, so to speak.

The full article appeared in Voice of Dance (http://www.voiceofdance.org) on November 4, 2009. To read it, click here.

Wiseman’s Lens on Dance

Frederick Wiseman’s La Danse: Le Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris / Film Forum, NYC / November 4-17, 2009

The Paris Opera, as seen in Frederick Wiseman’s La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet

Courtesy of Zipporah Films

The ticket line at Greenwich Village’s Film Forum November 4-17 for Frederick Wiseman’s latest grand-scale documentary, La Danse: Le Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris, will surely contain as many dance fans as film buffs. And I suspect the local dance crowd will enjoy the movie more. It offers extensive, if necessarily fragmented, footage of the Paris Opera Ballet’s remarkable skills, and the celebrated French company rarely visits the States. Dedicated movie-goers, especially those familiar with Wiseman’s complete body of work, are likely to be disappointed.

Wiseman’s earliest films–shot in black and white, which suited his subjects and his style–still remain his most meaningful works. He treated his topics lawyerly (prior to his film career he was a lawyer).

Frederick Wiseman

Courtesy of Zipporah Films

From his first film, the harrowing Titicut Follies (1967), in which he treats Massachusetts’ State Prison for the Criminally Insane, he piles up the evidence point by point like a star prosecutor, allowing concrete facts alone, unadorned by appeals to sentiment–or, indeed, any explication whatsoever–to reveal the obvious verdict.

Later in his film career, he was lured by the siren song of color, even later by the fiction that “everything is beautiful at the ballet,” which brought him into my own field, dancing. In 1993 he examined American Ballet Theatre; recently, the Paris Opera Ballet. In both films, he coolly inspects the dance company as an institution, but without much point that I can discern.

La Danse finds him applying his familiar tactics: He opens by placing the institution he’s scrutinizing in context. We see a stunning series of freeze-frame shots of Paris, moving closer and closer to the opulent Palais Garnier, where the phantom of the opera held sway, at least fictionally, and which the Paris Opera Ballet has long made its home. (Now it has a second home at the Bastille, about which the less said, the better, and Wiseman says nothing.) Throughout the film, these shots of the city and the Palais Garnier’s dark, claustrophobic underground corridors are repeated, but not as a respite from intense emotion, while giving emotion a wider and more natural vein, as Ozu used shots of wind-stirred trees and the like, but instead–well, why actually? La Danse has no easily discernable drama or intention. It just goes on “forever” (158 minutes, to be exact), then peters out.

Oddly, Wiseman doesn’t dwell on the gaudy magnificence of the Palais Garnier’s public spaces–the gilt, the marble, the mirrored halls, the bronze statues, the crystal chandeliers; we eventually catch glimpses of them as the camera follows a cleaner–but throughout Wiseman emphasizes the gloomy corridors and winding passageways of the interior, the flooding in the lower regions where fish have set up housekeeping, as well as the no-better-than-institutional studios and offices.

As soon as Wiseman has oriented us to the particular domain he’s chosen to examine–as always, in his films, a world in itself, sealed off from a wider reality–he introduces the people who inhabit these nondescript backstage spaces: the dancers, the element most likely to seize a viewer’s attention. We see them taking the daily morning class essential to professionals and then learning or rehearsing or being coached in their roles.

A scene from Frederick Wiseman’s La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet

Courtesy of Zipporah Films

The dancers’ bodies are exceedingly svelte, lithe, and strong–capable of marvels. These dancers are the survivors of a rigorous schooling from about age eight and an equally rigorous weeding out of the pupils not up to standard, throughout the decade that it takes to turn a child with the right anatomy and unquenchable desire into a professional dancer. The POB dancers’ technical prowess is stupendous, but everyone seems to take it for granted, and we never see how it came about; nothing is shown of the academy in which these “acrobats of god” are trained, though it is a unique institution in itself.

In the company’s studios, the ever-present coaches clearly make a dancer’s professional life that of an eternal student. They are forever being corrected, in order to attain some Platonic ideal of execution. These elders who supervise the rehearsals, usually once leading dancers themselves, are encyclopedias of information about how things were done in the past and what might be achieved now. Their bodies have thickened, their legs have lost their spring, but their eyes have become piercingly sharp.

As is typical of Wiseman, not one of the dancers or coaches is named. Similarly, the ballets we see excerpts from are not named; their choreographers unidentified, though some of them appear on camera to coach their own work. (Apart from the familiar nineteenth-century classics, the choreography is nothing to write home about.) This information is revealed only in the Shaker-plain closing credits, another Wiseman hallmark.

Wiseman’s familiar use of anonymity while revealing both personality and job description is best effected in the scenes involving Brigitte Lefèvre, the Paris Opéra’s director of dance–in other words, POB’s boss. Her calm yet steely authority and well-calculated empathy for her dancers (she was once one of them herself) emerge gradually but unmistakably from the several scenes in which she’s the focal point. You don’t know her name or exactly what she does, but you know what she is.

Wiseman persuades us to understand Lefèvre solely from how she behaves in a series of different situations in which she deals with dancers, repertory, casting, company policy, and money. This is no mean achievement.

It’s also in the scenes involving the administration that we begin to realize the grand scope and complexity of the POB as an institution. Wiseman also covers the scenic department, where thick but deft fingers are pictured adding gleaming paillettes to the tulle or velvet of a costume, the sewing crew working under short white tutus that are suspended from the ceiling like so many chandeliers. The more pedestrian aspects of a life in dance are recorded too, as in a view of the company’s cafeteria that, amusingly, offers us freeze-frames of dishes like the ones we accepted, faute de mieux, in college.

A scene from Frederick Wiseman’s La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet

Courtesy of Zipporah Films

The film progresses from work in the studios to rehearsals onstage in an auditorium hauntingly devoid of spectators. All of these activities and the behind-the-scenes work as well–a studio being spackled and painted, the dancers having their make-up applied–are arranged as a collage in time, but the elements are bricks without mortar to make them adhere, to build something. What does Wiseman himself derive from all the material he’s presenting to us? What are we to make of it?

Damned if I know.

Towards the end of this seemingly endless film without drama, climax, or even resolution, there’s a stirring, extended excerpt of a performance, by Delphine Moussin, of Medea murdering her children in Angelin Preljocaj’s eponymous ballet. And there’s been a very brief shot of the public entering the lobby of the Paris Opéra, with its exquisite curving double staircase, but to the best of my recollection, we never witness a dance being viewed by the public it’s meant for. And, sadder yet, we never hear it applauded.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias