Often the visual arts will make a dance fan feel he or she is in the presence of dancing that doesn’t move through space and time, but is dancing nonetheless, or at least its cousin. The actual dance pickings seemed slim this year, as summer slid into autumn. This is often the case, but never fear; we’re already beginning to be bombarded with choices. Still I thought I’d grant myself a busman’s holiday and see what the picture people were up to. The ambitious exhibitions at the grandest museums have long runs, so shows that I missed during this spring/summer’s hectic dance season are still up. The permanent collections of such museums remain more or less permanent, though the big museums can never display all they own at one time. For this piece, I treated myself to four offerings currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Vermeer’s renowned work The Milkmaid, on loan from Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, is the centerpiece of a special exhibition that runs through November 29. It’s joined by the Met’s own five Vermeers and other works, sometimes borrowed, related to it through the time, locale, and subject matter of their composition. The juxtaposition teaches a tough, true lesson about every art: competence enhanced by energy differs radically from sheer genius. None of his Netherlandish contemporaries in the seventeenth century holds a candle to Vermeer.

Johannes Vermeer: The Milkmaid

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Painted in the late 1650s, The Milkmaid shows a robust young woman who, from her rough clothes with their rolled-up work sleeves, her setting, and her action–standing at a table heaped with various magnificently crusty breads, carefully pouring milk from an unglazed clay jug into a low glazed bowl of the same material–is clearly a domestic servant. The simple room she stands in holds little but the woman, the breads–some roughly torn into pieces for the bread porridge she’s probably concocting–and a few culinary objects.

Two elements, however, suggest an additional dimension: a small foot warmer behind her (imagine the heat creeping upwards when it’s used) and a sketch of Cupid shooting an arrow from his bow among the Delft tiles set where the chalky wall behind her meets the floor. An art aficionado of the time would easily have recognized these as emblems of erotic love. Today the ordinary viewer may not notice them or think of their meaning, but surely, if he simply looks hard and steadily at the woman herself, he will suspect, from what Vermeer shows him, that she has a secret inner life, which lures him into contemplating what it might be. The very light in the room–coming only faintly from the window to her left, which contains a small broken panel (can it possibly suggest lost virginity?), while she and her work are bathed in a cool glow from an invisible source to her right–gives an uncanny luminousness and mystery to this sturdy woman.

In this, and in nearly all the pictures of his maturity, Vermeer shows himself to be the master of the beauty of silence, composure, and introspection. As in sublime adagio dancing, his pictures create an atmosphere of suspended breath. And as in most long-lasting ballets, a sense of a profound yet unspecified inner life, subtle and elusive, is exuded by Vermeer’s solo figures. Even his couples and somewhat larger groups intimate–in addition to their social relationships (lovers or seducers and the women they desire; mistress and maid)–something of each figure’s half-hidden self.

Like dancing–even when it’s abstract–Vermeer’s paintings are an instructive and poignant example of expression without words, without even specificity. They are examples of the enigmas that give the greatest art its soul.

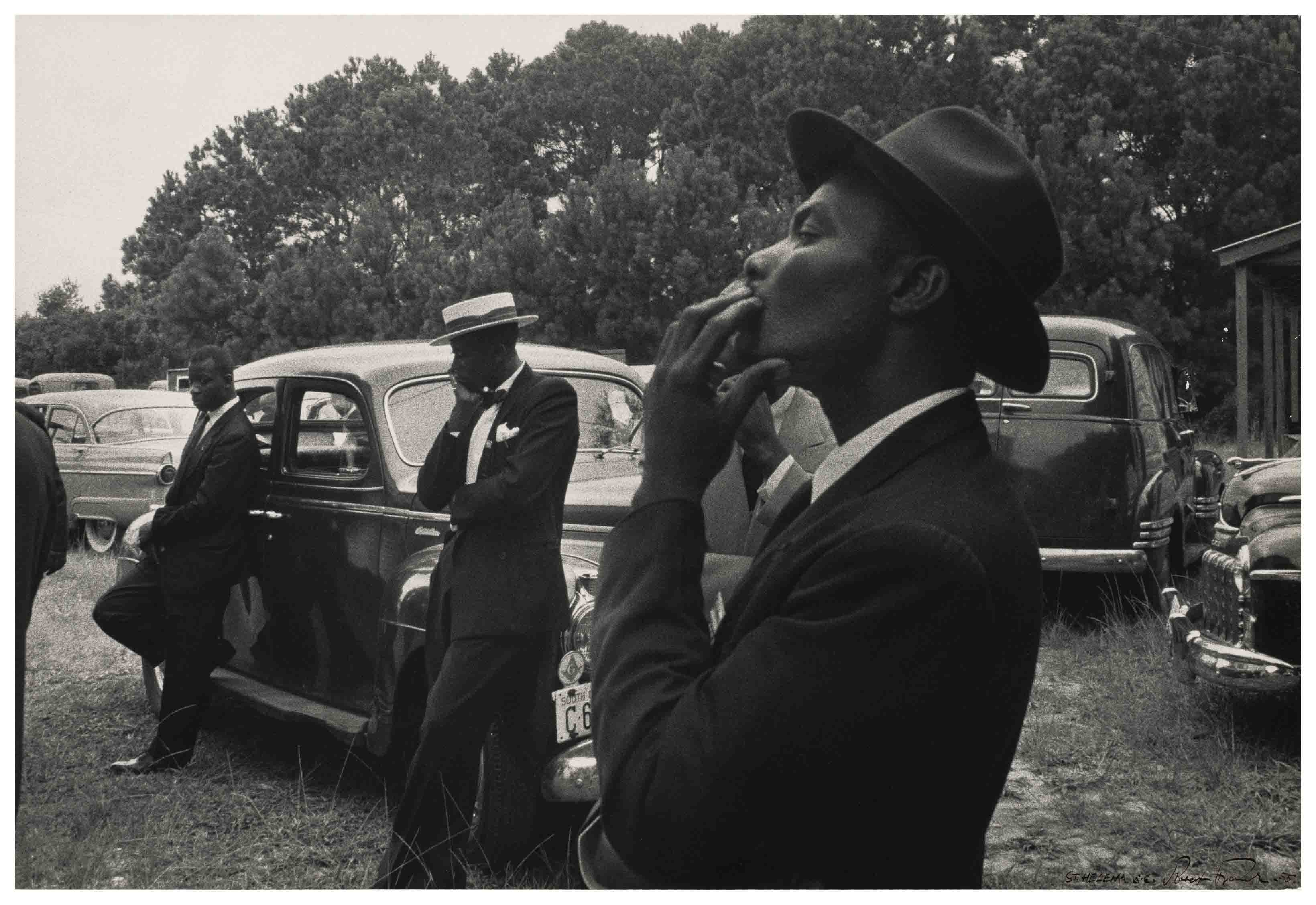

The justly celebrated photographer Robert Frank (1924 – ) focuses on the unvarnished truth about ordinary people, a subject explored in the early works of choreographers like Trisha Brown (in her early, bare-boned “task dances”) and Mark Morris (in the motley types of his first dancers’ bodies and his combining pedestrian moves with codified technique). Compellingly, Frank reveals his have-not subjects as they are, stripped of the appearance or behavior more privileged people use as a mask, attempting to present themselves to the world as they would like to be seen.

Robert Frank: Funeral–St. Helena, South Carolina

Photograph © Robert Frank, from The Americans

The Met’s current exhibition of his work, “Looking In: Robert Frank: The Americans” centers on the book of that name published a half- century ago, showing each of its 83 subtly riveting images with a generous addition of related material. The Swiss-born photographer, who emigrated to the States in 1947, drove a used Ford along a route that crossed the country twice in the mid-Fifties, shooting a vernacular America. He greatest sympathy seems to lie with the poor and with African-Americans–people with little power, financial, social, or political, so that their status ranges from the utterly ordinary to one that can’t help arousing the viewer’s pity. If these pictures are harsh, it’s because life is harsh, and often lonely, though the images include gaiety and human bonding as well as pathos.

Rich folks, the ruling classes, are naked in their pretensions in Frank’s images. But this photographer doesn’t preach, at least not openly; he records. Quoted in the show’s wall text, he says: “I am always looking outside, trying to look inside, trying to say something that is true. But maybe nothing is really true. Except what’s out there.” It’s reality he’s after. He grabbed it using a casual style that allowed low light, blurry focus, grainy images, and unconventional composition, according to Frank’s wishes and situation. This iconoclastic aesthetic had a major influence on photographers who came after him. And surely any dancer-choreographer who attempts to start building a vocabulary and a pattern for dance-making from scratch–Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham in her early career, Laura Dean–flouting traditional rules in pursuit of her or his own vision, is Frank’s kindred soul.

If Frank’s work is rooted in life’s reality, the paintings and drawings of Antoine Watteau, which dominated French art in the first quarter of the 18th century, present (or, more accurately, imagine) life as artifice.

Antoine Watteau: Mezzetin

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

In the Met’s current “Watteau, Music, and Theatre,” the elegance and poise of the body’s poses and the figures’ consciously graceful self-presentation (exuding charm tempered by a regretful melancholy); the soft titillation of an erotic subtext; and the evocation of Cythera, the Greek island considered Venus’s birthplace, thus an idyllic land of pleasant dreams, are seen in musical and theatrical settings. One can readily think of them rendered in a ballet–The Sleeping Beauty being the most obvious–or compare them to delicate, fragile porcelain figurines.

As a dance writer I can’t fail to mention the well-known picture by Nicholas Lancret (a follower of Watteau, though without his emotional power), which is included in the exhibition. It features the celebrated ballerina Marie Camargo in a garlanded skirt whose hemline she raised slightly above prevailing tradition so that the viewer might see her trim ankles in action. Nevertheless it’s another work in the show, a Watteau brimming with atmosphere, that continues to seize my imagination and refuses to let it go. Called Mezzetin, (after the commedia dell’arte character), it shows a seated man past his first youth playing a lute in front of what seems to be a theatrical drop curtain hazily depicting a generic leafy park sheltering the obligatory marble statue.

Perhaps this man once trained as a dancer; his exquisitely muscled lower legs are sheathed in silver stockings that emphasize their admirable form. Lavish fabric–of lush texture and an intense rose hue–dominates his costume, from his generous hat and cape to the outsize rosettes on his shoes. By contrast, his hands, fingering his musical instrument, are grotesque–even deformed–reddened and gnarled as if to represent the result of the life-long practice necessary to a musician or dancer who aspires to the rank of artist. The backward tilt of his body, especially his head, and his faraway gaze suggest a haunting nostalgia for beauty that must vanish–in art and in love–and self-indulgence in that gentle, bittersweet melancholy as well. Forget The Sleeping Beauty; think, instead, of Balanchine’s Emeralds.

.

It’s easy enough to call upon Degas to illustrate the connection between the visual arts and dancing, since dance was one of his primary subjects. But in the Met’s several rooms of this artist’s dance works, part of the museum’s permanent collection, we meet with the several aspects of Degas that exist. There are the pictures–in oils, pastel, or charcoal–of the female Paris Opéra dancers in performance; the studies of these dancers in rehearsal (notice their frequent boredom), in class (where they often stray from classical correctness), or at rest (where their exhaustion affects us viscerally); the bronze casts of small wax figures showing some of the oddest postures dancers assume, often while doing no more than examining the sole of their foot; and the drawings, often studies for work yet to be realized, Nearly all of these tell us that, at heart, Degas was not an artist of the pretty–as collections of reproductions on note cards often insist–but, at his truest, exercised the ruthless pair of eyes and deft hand of an anatomist. My favorite image in this last category–it burned itself into my brain long ago, though I can’t recall where I saw it–is a charcoal on, I think, blue paper, of an ankle and foot, in a soft ballet slipper. The foot is turned out and seen from behind. It is absolutely accurate, so the position seems very strange, especially as it’s unattached to a body that would give it a context. It is a perfect emblem of ballet.

On my Met visit I cottoned most to the over-familiar bronze figure of a child dancer (one Marie van Goethem) who was a student–one of the “little rats”–at the Paris Opéra. Strangely, the nearly life-size figure (first created in wax ca. 1880; cast in 1922) is adorned with some fabric: she wears a ragged-edged dancing skirt of coarse weave ending just above the knee, while the bronze braid that falls down her back is tied with a long-streamered bow of faded pink satin ribbon. Her right leg is thrust forward, as in fourth position, but it’s loose-kneed and takes no weight, as if she were “at ease,” between the more strenuous efforts of her trade. Her arms are pulled straight behind her back, hands clasped, the pose emphasizing her touching slenderness. The most eloquent part of her is her head, tilted defiantly upward with unquenchable pride.

She made me think of the little girls of the New York City Ballet’s academy, the School of American Ballet, each with her pluck, her self-assertion, and her desire to have the world understand she is a member of the elite and that though she may be a mere–oh, let’s say–advanced-beginner in her exotic trade, she has at least been selected as worthy of training, and her aspirations are sky high.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias