American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / May 18 – July 11, 2009

As celebrated in Russia as the Mississippi is in America, the mighty Dnieper River has accreted to itself a history, an atmosphere, and a mythology that reaches out to several arts–just as Mark Twain’s masterwork, Huckleberry Finn, for example, is bound to the Mississippi.

Rushing to the Black Sea, the Dnieper passes through Ukraine, where Alexei Ratmansky, the new Artist in Residence at American Ballet Theatre, first danced professionally. Working to the Prokofiev score originally choreographed by Serge Lifar in Paris in 1932, Ratmansky put his singular ingenuity into his own version of On the Dnieper–a 40-minute ballet deriving its title from the music, which is considered his first official work for ABT. (A pièce d’occasion for the gala showcasing Nina Ananiashvili, which opened the company’s May 18 – July 11 season at the Metropolitan Opera House, apparently doesn’t count.)

Like all of Ratmansky’s work that I’ve seen, On the Dnieper reveals the multiple influences on the formation of his aesthetic: training in the Bolshoi Ballet’s academy in Moscow, then, when rejected for admission to the parent company, performing as a principal dancer with the Ukraine National Ballet, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, and the Royal Danish Ballet, and choreographing for prestigious companies from St. Petersburg’s Kirov Ballet to the New York City Ballet. For some four years he has been the artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet and one of its most inventive choreographers, at times taking his inspiration from Soviet-era ballets once thought better forgotten and making them utterly new and delightful, as with The Bright Stream. Now he has given up the leadership of the Bolshoi, with its soul-devouring administrative demands, to concentrate on his choreography.

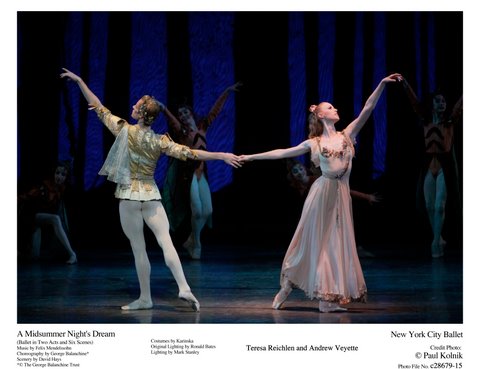

Marcelo Gomes, Veronika Part, and Paloma Herrera in Alexei Ratmansky’s On the Dnieper

Photo: Gene Schiavone

On the Dnieper tells a tale that the Romantics among us will believe in, others not. Sergei (Marcelo Gomes in the first cast, as are the others I name) returns from World War I to his beloved native village, indicated by weathered wooden fences, and the poignant springtime sight of blooming cherry trees just beginning to drop their petals. Though welcomed by his fiancée, Natalia (Veronika Part), he’s distracted by Olga (Paloma Herrera), the community’s vivacious beauty who has already developed a distaste for the fellow to whom she’s engaged (David Hallberg). Parental figures and the young people of the village surround them, witnesses and judges as the plot plays itself out–with much self-recrimination on Sergei’s part, and a selfless renunciation in favor of Olga on Natalia’s part–to an ecstatic happy ending amid a veritable storm of petals, in which love conquers all. Yes, the program note is needed, but Ratmansky comes closer than most dance storytellers to indicating situations and, especially, deep feeling directly through his choreography.

What I like best about this ballet is its mood. Without making a melodramatic fuss, it supports the primacy of feeling, the respect for social behavior (at its moral base and in its formal traditions), and the wrenching conflict between those and the pull of the unexpected, often inexplicable, desires of the heart. It evokes the world as imagined by Tudor and by Chekhov.

Herrera, I’d venture to say, has never danced more eloquently. Finally, no doubt largely because of Ratmansky’s ballet, she’s realized that bravura technique cannot, alone, make a ballerina. In On the Dnieper she’s exploring the realm of fusing her extraordinary physical prowess to a range of emotion. I hope the revelation of this possibility will carry through to the rest of her repertory; it could make her glorious.

Gomes, as always, has a commanding presence and here he lives up to the way he looks. At the same time, he is very affecting in his confusion and regret when he realizes that, for his own happiness, he must betray a sensitive woman he once loved. He needs only a little more detail and nuance, the patina a role acquires with time in the hands of a resourceful interpreter.

Part is just right for the reticent sensitivity of the abandoned, self-sacrificing sweetheart. I was touched by the moment she “gives” Sergei to Olga and they bow to her formally, then rush off, elated, to their future and she falls to the ground, unwitnessed in her anguish. She’s the one character that made me think of her future–never marrying, I fantasized, becoming a nun or a nurse to the incurable, anything that would allow her to give her life to succoring humanity and expunge self-interest from her soul. The fact that Part’s role is about emotions rather than famously difficult steps relaxes her frequently visible mistrust of her technical abilities, freeing her as a creature of the stage.

Hallberg, unfortunately, has a role that doesn’t show him to any particular advantage, though he may, like many a wise dancer, make something better of it as he performs it more.

It was fun to see the seniors associated with the company (teachers, coaches, regisseurs, and the like) in the parental roles and wonderful to see a corps de ballet convincing in its robust dancing and in its walkaround roles as well, as witnesses, abettors, and benevolent spies–roles that make a community cohere.

For reasons I can’t fathom, ABT’s artistic director, Kevin McKenzie has returned to the work of the Canadian James Kudelka and Prokofiev’s Cinderella score, after adding the choreographer’s self-consciously quirky program-length version of the fairy tale to the repertory three years back, without much success.

Kudelka’s 1991 Désir, given its ABT premiere on this season’s Prokofiev program, is a plotless one-acter that uses the only four remarkable passages in the Cinderella score and two other numbers gleaned from the composer’s Waltz Suite (reworked from his opera War and Peace). The dance is a pretty little thing, nothing more, admittedly useful to fill out a mixed-repertory program, but essentially insignificant.

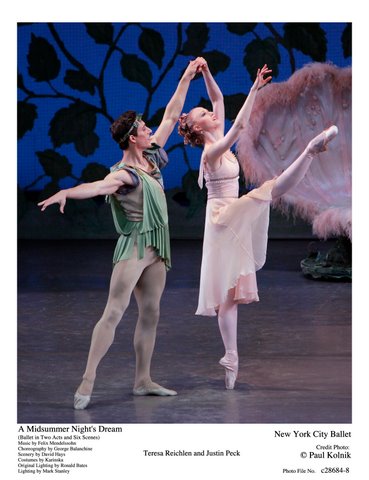

Isabella Boylston and Cory Stearns in James Kudelka’s Désir

Photo: Rosalie O’Conner

Two couples, one of them (Gillian Murphy and Blaine Hoven) opening the piece, the second (Isabella Boylston and Cory Stearns) appearing midway through, demonstrate joyous, fulfilled love, the first pair with an allegro pulse, the second in an adagio mode.

Misty Copeland and Carlos Lopez seem equally content, but they introduce a small ensemble expressing the doubts and tensions that arise between the sexes. Clusters of closely bonded young men and similarly united young women reflect the emotional difficulties of moving beyond a single-gender group. I think. This is not the clearest ballet in the whole world.

The movement is often soft and curving, over a firm ballet base. Nothing you haven’t seen before. The dance would benefit from a wider, more inventive vocabulary.

There is no hint of a subplot behind the activities, several of which are incomprehensible. Why do the men repeatedly stretch out supine and stiff? Is this a premonition of death? What’s the meaning of a repeated frozen arm position in which the women hold their full skirts bunched into a bundle in front of their bellies, like a wedding bouquet or its logical aftermath?

The best elements of the piece are the gorgeous costumes by Marjory Fielding (designed for the National Ballet of Canada production)–and the presence of Isabella Boylston in the first cast. Boylston has an uncanny calm that rivets the viewer’s attention, even when she’s tossed into the air and flipped backward by her partner. She has the face of a Flemish Madonna, a long, suavely proportioned body, and impeccable technique. In repose, she seems sculpted from marble; in motion, she’s like that cool, noble stone magically endowed with fluidity. The fact that she has incredibly beautiful feet is underlined by the duet’s finishing with her partner’s extending his body along the floor to kiss one of them. The gesture is embarrassing, though, at odds with the formal tone of the duet, and entirely unnecessary. However, Boylston, still a corps de ballet dancer, deserves promotion to soloist rank on the performance of this role alone.

As for the costumes, the women’s ankle-length dresses have a subtly composed palette of colors related to fuchsia and fire-truck red. They’re set off by one in muted blue, another in intensely deep violet. The lavish skirts swirling in unison have a ravishing effect. The men wear casual t-shirts in shadowed tones that echo the women’s gowns; they top workaday trousers of burnt sienna. The women are flowers; the men, the earth from which they spring.

One way to sell tickets to the ballet (or to sell anything else, for that matter) is to cause a sensation. In the States, the general public that comes to the ballet loves a sensation (for one thing, it justifies the cost of the tickets) and does its best to exaggerate the dimensions of one with wild cheers and applause during the performance, escalating into feverish standing ovations and bouquets from the spectators pitched onto the stage at the end.

Natalia Osipova in August Bournonville’s La Sylphide

Photo: Marc Haegeman

During ABT’s current season, the Bolshoi Ballet’s Natalia Osipova–whose fleet, airborne technique took my breath away in 2005 in a solo in her company’s Don Quixote–did a stint that I assumed to be a tryout for a larger guest association with ABT in the future, dancing the title role in two Romantic-era ballets, Giselle and La Sylphide.

Sensations, however, have only a tangential connection with artistry. Osipova’s elevation (an issue of hip flexibility and leg power) and fleetness (foot articulation and power) are near miraculous. So much so that they have become phenomena–the feet working like hummingbirds’ wings, for instance–not really the province of dancing anymore. Other parts of her body have been neglected: her face doesn’t create the illusion of beauty that enhances a ballerina; her torso has no fluidity. She has also obviously been over-coached, a fact that destroys the childlike naturalness she had when I first laid eyes on her.

Giselle was the better of her two portrayals, thanks in part to the sympathetic partnering of David Hallberg. Still, with emotions coursing through her one after another at febrile speed, none of them lasted long enough to register and eventually add up to something coherent. And her continual grinning in Act I, as if this were an emblem of joyous, innocent love, should have been squelched at the first rehearsal. Her subsequent Mad Scene was reasonably good, if still immature.

In the second act, Osipova carried everything before her, seeming to fly and whirl at once when initiated into the ghostly tribe of wilis by a wonderfully malevolent Veronika Part. Still, the necessary change in movement texture between the live girl and the dead one who still retains her early passion for her lover, forgives him, and saves his life, was absent. I would guess she understands the difference intellectually, but can’t yet make it happen physically. If, with time, experience, and sound professional advice, she still doesn’t, her sensational effects are likely to deteriorate into mere circus tricks.

Osipova’s La Sylphide was a disappointment. Her particular gifts do little to evoke the enchanting Bournonville style (which the Russians have never mastered and the Danes themselves are losing) in its phrasing, irrepressible ebullience, or charm. Her partner, Herman Cornejo, who seems to be able to adapt to any style he tries, was the hero of that performance.

June 27 saw Nina Ananiashvili’s farewell performance with American Ballet Theatre. She took on the celebrated dual role of Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, the very thought of which can make a ballerina two decades younger than she quake in her pointe shoes. (Ananiashvili is 46.) The performance was extraordinary; I’ve never seen anything like it. Throughout, she demonstrated the exquisite technique that she has honed to perfection over the decades, but here, in the “white acts,” she added little miracles like executing the mime passages, as in her relating her woeful story to Prince Siegfried (Angel Corella)–“my mother’s tears formed this lake”–so fluidly it became the veritable cousin of dancing. Then, with a masterly containment of emotion so profound it was almost unbearable, though devoid of obvious acting, she made the dancing so refined it looked abstract. If classical dance can be transmuted in the equivalent of an Ozu film, this was it.

Nina Ananiashvili in Kevin McKenzie’s Swan Lake, after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov

Photo: Nancy Ellison

Instead of the cheap thrill of the full 32 fouettés (which, by the way, neither Margot Fonteyn nor Maya Plisetskaya ever mastered) she did a mere 24 as neatly as could be imagined and wisely quit while she was ahead. As if to make it up to the audience this slight diminishment of bravura, she executed a surprise carnival-style move in which Von Rothbart (Marcello Gomes at his sexiest) threw her high into the air to be caught in the deluded Siegfried’s arms. The three repeated the feat on the curtain-calls, much to the delight of the madding crowd.

In the Black Swan act, Ananiashvili’s rendition was tantalizing enough to contrast with her Odile, and some of her feats, though subtly executed (such as long balances in which she seemed to stretch up and out as on a breath) were remarkable. She made a quiet though compelling seductress, though, admittedly, her Odile doesn’t seem as truly evil as her Odette seems good by nature’s design.

The bows themselves, which seemed to run on hourglass time, rather than that of a stopwatch, constituted a ballet within themselves and were designed with unusual good taste. Even the single explosion of confetti, white and gleaming, looked like a falling star in a fairy tale instead of the familiar torn up paper drifting listlessly through a net. My favorite moments were the cast’s applauding the ballerina, and she, them; Ananiashvili’s personally presenting one white flower to every single corps de ballet swan; ABT’s other ballerinas, in svelte black mufti, coming on to offer the heroine of the hour a long-stemmed blossom, followed by her male partners in the company, and, later, the artistic director himself, Kevin McKenzie, to whom Ananiashvili bowed low as she had to the Russian coach and to the former Kirov prima, Irina Kolpakova; the appearance of the ballerina’s little copper-haired daughter, whose mom promptly enough shooed the child back into the wings after a bow or two; Ananiashvili’s catching in one hand bouquets that the audience hurled at the stage, simply snatching them out of the air. You might say she has a gift for coordination.

Curtain call for Nina Ananiashvili’s farewell performance with ABT.

Photo: Gene Schiavone

Ananiashvili’s final season with ABT has included some of the most demanding roles in the nineteenth-century classical repertory in terms of dancing and acting: In addition to Swan Lake, she did Giselle, La Sylphide, Le Corsaire, and, from the twentieth century, Balanchine’s sublime and eccentric Mozartiana. She flourished in all of them but the Bournonville and there she was simply at the mercy of the wrong-headed Erik Bruhn production staged for ABT a half-century back and what seems to be a standard Russian interpretation that makes the characters look crude. And then there’s the inevitable awkwardness of the Bournonville style for dancers who haven’t been trained in it from the start (ABT’s Herman Cornejo and the American Lloyd Riggins are the only dancers I’ve seen overcome this challenge convincingly).

At the opposite end of the spectrum, a pair of Giselles I saw, differently tempered because danced with two different partners, were luminous. With Marcelo Gomes, Ananiashvili matched the power of his stage presence; with Jose Manuel Carreño, she echoed his more understated, yet emotion-filled approach, effortlessly launching shape after beautiful shape into the air, then letting them dissolve into the flow of the dancing.

Moving through the trajectory of Giselle’s story, Ananiashvili gives us both the shyness and blitheness of an innocent girl utterly in love; the suddenly distorted landscape of a woman literally broken-hearted by that lover’s betrayal; then, beyond the grave, a mature sorrow for his plight, his anguish as well as an enduring devotion that saves his life. As the story unfolds, we come to know a remarkable person who remains nakedly true to herself from beginning to end, one of those rare human beings wrapped in a cloak of tenderness.

Ananiashvili’s Mad Scene–the result, no doubt, of years of thought, experiment, and minor but telling adjustments–is an example of how the wholeness of her performances is now invariably extraordinary, every detail of movement and feeling perfectly accounted for, anything extraneous firmly excised.

In both Giselles, she gave us immaculate dancing that was nevertheless softened and full of grace. Yes, her grands jetés cleave the air, but they seem as downy as rose petals. In her high-speed whirling initiation into the tribe of wilis, her legs swathed in the layers of her tulle skirt, her foot barely grazes the floor as she turns herself into a gossamer cloud caught in whirlpool of wind. Her grace has a spiritual dimension, too, that makes her Giselle real, loveable, and tragic, and it is this quality–of the soul perpetually infusing the body–that make our hearts hers.

Ananiashvili’s many fans may wonder why this much beloved ballerina would withdraw from the big time when her technique was still up to the challenges of such works and her artistic powers were at their height. Reasons for such major decisions depend greatly on instinct–what your heart or gut is telling you. But Ananiashvili is practical enough to placate her audience (and, perhaps, herself) with a handful of practical arguments in favor of bowing out: to support her husband, Grigol Vashadze, Georgia’s Foreign Minister, who is pursuing a burgeoning political career, just as he has helped her in the last two decades of her career; to spend more time with their young daughter, Helene; to further the development of the State Ballet of Georgia, based in her home town of Tbilisi, which she was specifically brought in to head in 2004; and because she knew–and admitted to herself, as so many dancers are unable to–that the body’s abilities inevitably fade with age. Any one of these reasons would be persuasive.

There’s no denying that a significant part of Ananiashvili’s appeal is her sheer physical loveliness. Her face, with its creamy skin, dark hair, and heavily browed, soulful dark eyes, has the cast of a Spanish Madonna. Underneath that look is an instinctive empathy for the characters on stage around her. Her long, exquisitely proportioned body seems destined for classical dancing. Her promise of beauty and the perfect poise of her body–a natural harmony–is evident even in snapshots of her as a child. Complementing these attributes is a melancholy frequently underlying even her most vivacious roles, where her smile is infectious, even teasingly flirtatious, yet her eyes suggest that she knows that everything in life is evanescent.

From her first engagement with an American company (a guest stint with the New York City Ballet in 1988), we’ve seen how smart she is, how open to ideas about dancing that are radically different from the Russian ones in which she was scrupulously bred. She was accompanied in the venture by her celebrated Bolshoi colleague Andris Liepa, who continued to do everything in the Russian way familiar to him, while Ananiashvili tried to absorb Balanchine’s way.

In the course of her sixteen years at ABT, we’ve watched the harmony and flow of her dancing in the lyrical vein become more and more beautiful and natural, like the motion of a nymph–a naiad perhaps. The steely aspect of her personality has served her in good stead–both in her dancing, when virtuoso passages require it, and offstage in shaping her career and leading the State Ballet of Georgia, essentially a pleasant regional company that the government is eager to upgrade. She is also blessed with a sense of humor, which Alexei Ratmansky caught in Waltz Masquerade, the pièce d’occasion he created for her to perform at ABT’S opening night gala. It might have been called “The Diva and Her Devotees.”

Diane Solway, interviewing Ananiashvili in W Magazine, asked the ballerina what she’d be doing after her farewell performance with ABT. The answer: “Crying.” Her tears were not the only ones shed on the occasion.

© 2009 Tobi Tobias