This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on October 3, 2008.

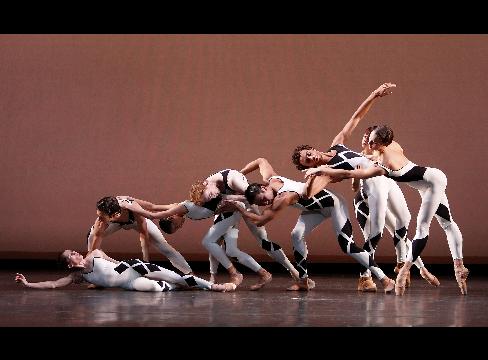

Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company dancers take part in a performance of Christopher Wheeldon’s “Commedia” at the New York City Center in New York, Oct. 1, 2008. Photographer: Erin Baiano/Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company via Bloomberg News

Oct. 3 (Bloomberg) — Morphoses/The Wheeldon Company is still a dance troupe in the making. At the New York City Center through Sunday, it features a cluster of international stars moonlighting to support Christopher Wheeldon’s branching out on his own after seven years as resident choreographer of the New York City Ballet. Since forming his group, he has also benefited greatly from the institutional support of City Center and of London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre.

The first of two programs contradicted Wheeldon’s brashly expressed desire of “making it new” — saying goodbye to Balanchine and all that. In his pre-curtain speech at opening night on Wednesday, he talked about looking to the past for the way to the future; his own recent “Commedia,” set to Stravinsky’s familiar “Pulcinella Suite,” underscored this. Referring to the glory days of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (which included Massine’s “Pulcinella” in its repertory), it translates commedia dell’arte-style cavortings and romances into Wheeldon’s own cool style, deliberately calling attention to its inventiveness. Its best feature is a love duet typical of this choreographer in its all too self-conscious charm.

The other new work on the bill was Morphoses’s first independent commission, which one can only hope is not prophetic. Canadian Emily Molnar’s “Six Fold Illuminate,” set to Steve Reich’s “Variations for Winds, Strings, and Keyboards,” suggests that if ever a composer and choreographer were ill-matched, it is this pair.

Hypnotic Spooling

Instead of responding in kind to the music’s hypnotic spooling out of delicately varied repetitions, Molnar has two women and four men endlessly showing us flesh being hauled around — by its owner or partner — as if it were heavy meat. In the two main duets, the battle of the sexes is rehashed with ever-deadening hostility and co-dependency.

Neither of these creations competes with — or even complements — Wheeldon’s 2001 “Polyphonia,” which introduced the current program and was sveltely performed.

Along with the 2002 “Morphoses,” these works — both to Ligeti scores — made the young choreographer’s name. He hasn’t topped them yet. Meanwhile, Frederick Ashton’s sublime “Monotones II” got a sub-par rendition, while the ravishing central duet from that master’s “The Dream” has been relegated to the second program.

Wheeldon’s fame rests on the fact that no one in his generation could rival his suave practical skills in making a contemporary classical ballet. Given the fact that he absorbed and processed so intelligently lessons from the work of Ashton and Kenneth MacMillan in his early dance life with England’s Royal Ballet, and George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins when he joined the New York City Ballet, admirers were willing to overlook a certain sameness in his style and its seeming lack of heart.

Now he has a rival in the Bolshoi Ballet’s artistic director Alexei Ratmansky, who went through a decade of peripatetic alliances, learning about Western dance without sacrificing his Russian roots. His works (including “Russian Seasons” and “Concerto DSCH,” made for City Ballet) have been much appreciated in the U.S. for the very humanity that’s missing in Wheeldon’s.

After an awkward flirtation with City Ballet, Ratmansky recently accepted a five-year appointment as artist in residence with American Ballet Theatre. Perhaps the competition will benefit both choreographers. It will certainly be engaging for audiences.

Through Oct. 5 at 131 W. 55th St., Manhattan. Information: +1-212-581-1212; http://www.nycitycenter.org.

© 2008 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.