This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on October 3, 2007.

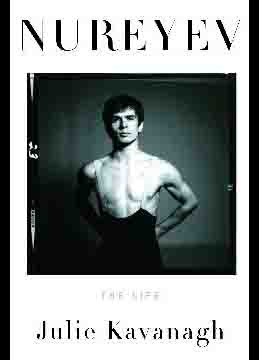

The book jacket for “Nureyev: The Life” by Julie Kavanagh is pictured in this undated handout image. Source: Pantheon/Schocken Books via Bloomberg News

Oct. 3 (Bloomberg) — At its height, Rudolf Nureyev’s dancing combined the feral power and beauty of his movement with a passionate, volatile temperament. He transformed his raw gifts into a sleek professional style — part Russian, part European – -without ever giving up his spontaneity. Wildly flamboyant and deeply soulful by turns, he seemed to live the characters he portrayed as if they were his alter egos.

Julie Kavanagh’s “Nureyev: The Life” relates in great detail the saga of a boy born of Tatar stock in 1938, who achieved fame equal to Nijinsky’s and died, after a long battle with AIDS, in 1993.

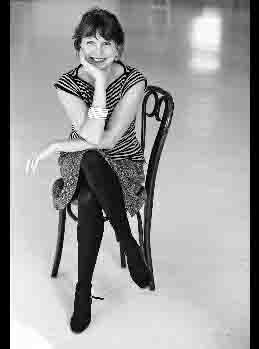

Julie Kavanagh, author of “Nureyev: The Life,” poses on Jan. 23, 2007. Photographer: Arthur Elgort. Source: Pantheon/Schocken Books via Bloomberg News

Her obsession with minutiae sometimes undermines the drama of Nureyev’s life, though the tale of his defection to the West is told with energy. To her credit, Kavanagh makes it clear that Nureyev was born to dance to his own tune and that, despite the damage he did to others and some dire consequences for himself, he was an incomparable artist who made the world a more thrilling place.

As a child during World War II, Nureyev, his mother and three sisters (his father was nearly always away on military duties), led a life of bleak deprivation near the provincial town of Ufa. When he was 7, his mother snuck her four children into a ballet performance on a single ticket. By the time the final curtain fell, Nureyev had committed himself heart and soul to dance.

His innate gift for dancing — spirited, musical, enhanced by his charismatic personality — had surfaced early on in kindergarten folk dancing. His innate rebelliousness appeared early, too, as did his ability to use people to further his career.

Insatiable Hunger for Art

From adolescence on, Nureyev demonstrated an insatiable hunger for the arts — dance, of course, which he pursued with a future saint’s sense of vocation — but also music, painting, theater, books and architecture. He was equally curious about people from foreign milieus, forging acquaintances the Soviet system would strictly forbid.

In the course of his life, Nureyev had a half-dozen nearly impossible dreams. He wanted — indeed, expected — to be recognized as the greatest dancer in the world. Even when age and illness had diminished his incomparable technique, ecstatic viewers thought he was just that.

He was determined to train at St. Petersburg’s celebrated Vaganova Academy, which fed the Kirov Ballet, to him the epitome of aristocratic elegance. Against all odds, he managed do so, worked fanatically and became one of the company’s best hopes.

Spontaneous Defection

Then he needed to escape from the repression of the Soviet system, aggravated in his case by his homosexuality and the conservative rigidity of the Kirov at that time. His dramatic defection — long dreamed of but spontaneously achieved in a Paris airport — came in 1961 and led to his international career.

Nureyev also yearned to absorb the cool perfection of the Danish legend Erik Bruhn. Polar opposites in temperament and style, they did indeed influence each other’s dancing and conducted an intense and tempestuous love affair to boot.

He danced with Margot Fonteyn, the Royal Ballet’s prima ballerina, an adored exemplar of radiant lyricism and almost 20 years his senior. Their partnership became legendary.

Only one wish remained unfulfilled: He longed to dance for Balanchine, a pairing that failed because Balanchine was certain his choreography would be undermined by superstars.

All in all, Nureyev did better for himself than most mortals.

“Nureyev: The Life” is published by Pantheon Books in the U.S. and by Fig Tree Press in the U.K. (782 pages, $37.50, 25 pounds).

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.