This article originally appeared in the Culture section of Bloomberg News on October 30, 2007.

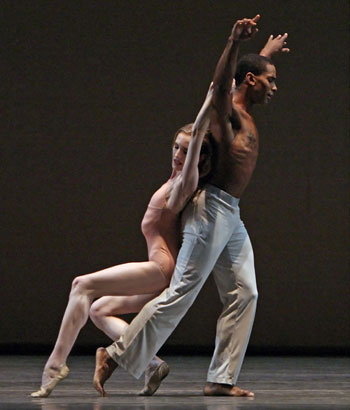

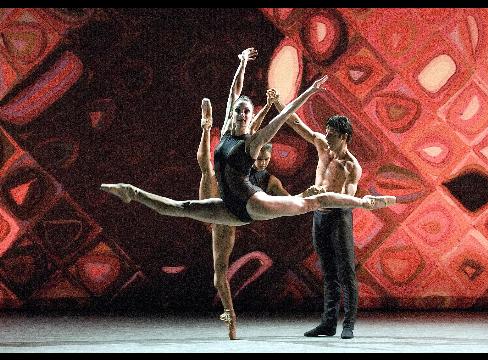

Kristi Boone, Misty Copeland and Marcelo Gomes perform in “C. to C. (Close to Chuck),” in this photograph released to the media on October 29, 2007. Photographer: Gene Schiavone/American Ballet Theatre via Bloomberg News

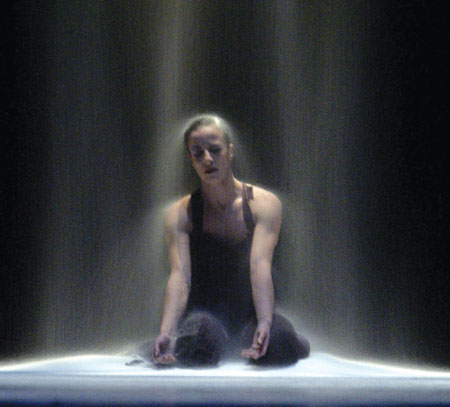

Oct. 30 (Bloomberg) — A strong sultry beauty in a dark gleaming unitard struggles endlessly in her powerful partner’s embrace. Or is it a stranglehold?

The forceful episode serves as the centerpiece of choreographer-on-the-rise Benjamin Millepied’s new “From Here On Out” for American Ballet Theater, performing at New York’s City Center this week. The duet’s subject seems to be a cruel co-dependency that masquerades as love. Remarkably, the choreography conveys no human feeling, neither depicting nor eliciting empathy. Its extravagant shapes and ferocious energy are merely decorative.

The balance of the ballet has five other anonymous, look- alike couples making the stage vibrate with their attack — as partners and in phalanxes, the sexes sometimes set against each other.

The important components are unbelievably svelte, fluid bodies, killer speed and menacing glamour. Nico Muhly’s score, percussive and haunted, fits the occasion perfectly. The overall effect is a sleek portrait of contemporary high-end urban life. The ballet — cleverly constructed, to be sure — offers a snapshot of the direction classical ballet is taking today.

`C. to C.’

If Millepied’s ballet pictures the world as an ominous place, the currently popular Finnish choreographer Jorma Elo contends that its inhabitants are chronically spastic. He applies this signature style to his new “C. to C. (Close to Chuck),” which looks like a sextet of robots aiming to add sex to their skill set.

The dance is choreographed to Philip Glass’s “A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close,” the score played onstage by pianist Bruce Levingston. Close, whose art figures as a backdrop, is the painter who heroically managed to continue his career after being paralyzed by a spinal aneurysm. Close, Glass and Elo all build their art from small fragments, hypnotically repeated with slight variations. However, the painter and composer make the whole cohere, brilliantly. I can’t say the same for the choreographer.

In “C. to C.,” as usual, he has his dancers executing disconnected, unfathomable gestures, even occasionally breaking into a few brief flowing phrases. Invariably, though, potential partners can’t relate to each other with any ease or joy — or even meaningful hostility. The costumes, by the fashion designer Ralph Rucci, are striking, until the wearers have to shed their stiff black skirts and move.

`Ballo Della Regina’

The brief season managed to cram in several terrific golden oldies, among them George Balanchine’s 1978 “Ballo della Regina,” an abstract piece for a hierarchy of women and a single man, set to an outtake from Verdi’s “Don Carlos” that begs to be danced. Originally it showcased the scintillating technique and unaffected style — both echt-American qualities – – of the New York City Ballet’s Merrill Ashley. As staged by Ashley for ABT, the production is a little miracle — crisp and clear, as if it were happening in the sky on a bright, windswept day.

I saw Gillian Murphy in the ballerina role and, while no dancer can ever replace another, she did Ashley proud. Murphy’s partner, David Hallberg, charging through space, whirling as if in a vortex, eclipsed even his personal best. The four soloists and the corps de ballet looked elated, as if they’d been schooled in a mode of dancing they’d never dreamed of.

The revival of Antony Tudor’s 1975 “The Leaves Are Fading,” a plotless nostalgic idyll, served as a reminder of the choreographer’s long-term association with ABT and the profound feeling a physical gesture can convey. Staged by Amanda McKerrow and John Gardner, both of whom once danced in it, it hasn’t yet retrieved the flow and spontaneity with which Tudor himself had his dancers perform his ingenious designs.

Still to come is the company premiere of Twyla Tharp’s 1979 “Baker’s Dozen,” an early work full of ingenious, ramshackle joy. All three blasts from the past are only a small part of the proof that the 1970s was an exceptionally rich period for choreography. What does the first decade of the 21st century offer to equal it?

Through Nov. 4 at City Center, 131 W. 55th St. Information: +1-212-581-1212; http://www.abt.org.

© 2007 Bloomberg L.P. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.