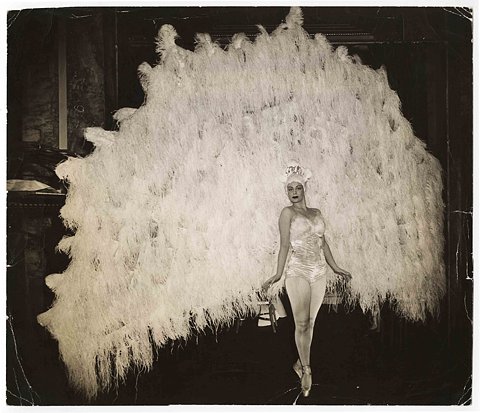

Three-quarters of a year ago, struck by an image, I wrote about a dancer whose history was essentially unknown. Here is the image–

Weegee

Ballerina Marina Franca in her peacock costume, April 18, 1941

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee / International Center of Photography

–and here is the essay. A brief passage in it now seems prophetic: “Contemplating this lady in her outlandish white costume–all shimmer and froth–we wonder: Who is she? How did she arrive at this time and place? This peculiar destiny? What does her “performance” consist of? Is she, perhaps, a reluctant collaborator in her work?”

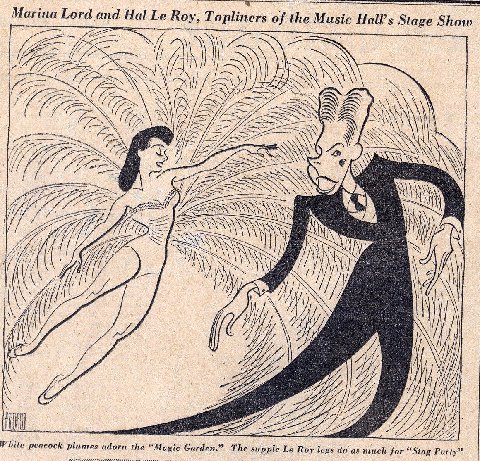

A couple of seasons after the essay appeared, I received an e-mail from Marc Salz, a Philadelphia-based painter in his late fifties, who identified himself as the dancer’s son. Since then, through the instantly informative yet strangely remote means of e-mail, he has filled in Marina Franca’s story. He also provided me with my first sight of Al Hirschfeld’s dashing image of her. Featuring the same outré peacock costume that caught Weegee’s eye, it recorded Franca’s appearance in the stage show at New York’s most extravagant picture palace, Radio City Music Hall.

© AL HIRSCHFELD. Reproduced by arrangement with Hirschfeld’s exclusive representative, THE MARGO FEIDEN GALLERIES LTD., NEW YORK. WWW.ALHIRSCHFELD.COM

Marina Franca, Salz relates, was known as Marina Lord at the time of the Radio City gig. Her real name was Wilhelmina Roothooft. She was born in Amsterdam in 1917. In her mid-teens, she decamped for Paris to train for a career in classical dance with the great Russian émigrés who had themselves relocated there. She studied first–in 1932–with Alexander Volinine, then made her debut in 1934 at the academy run by Lubov Egorova. In the late thirties, she studied with Olga Preobrajenska, where Léonide Massine discovered her and introduced her to the Ballet Russe.

The outbreak of World War II abruptly ended Franca’s 1938-1939 stint with the Ballet Russe. Salz explains the situation this way: “My mother was separated from her family (her mother and her younger brother, Edmond, in Holland, and her elder brother, Jan, who was in hiding in France). Her father had died earlier, when she was thirteen. She had been sending her mother money for support, she told me, but was otherwise cut off from communication with her family by the Nazi Occupation.

“She left for America, where her career choices were based on her own survival, of course, but also upon her concern for her family abroad. At first she tried her luck in Hollywood, but that didn’t work out for her as it did for another Ballet Russe dancer, Marc Platt. I have a number of publicity photos of her from that time; she even did an ad for ballet slippers.

“I think her post-Ballet Russe career must have been humiliating to her,” Salz continues. “Her training and talent were of a far higher caliber than the things she had to do to survive. The peacock costume, for instance. She couldn’t have done much dancing in it. It had a motor in the back that activated the peacock’s ‘display.’ It was almost a burlesque contraption. I think the Weegee photo captures her nervous unease at her situation.

“At the time of the peacock costume, my mother’s ballet career was clearly in trouble. I think she assumed that the choreographer of the moment, George Balanchine, would not care for her figure and style. First of all, he would probably think she was too zaftig. And then his connection with Stravinsky made his choreography more angular and formal–almost the opposite of the old-fashioned Russian School in which my mother was trained and the lighter French style of the Ballet Russe.

“She then met Sam Salz, a well known art dealer, who was 22 years her senior. They married in 1942. Sol Hurok, the ballet impresario, was the matchmaker. They lived first at a hotel on Park Avenue, where my father had his headquarters, selling Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. When they bought their own house on East 76th Street, it became the new center for my father’s art dealing. Meanwhile, they had produced two sons–me, and my brother André, who is a year younger.

“My mother disliked my father’s insistence that his gallery and his domestic life occupy the same space. The “customers,” who included Rockefellers and Mellons, came in the evening as well as the daytime. We were all told to be very quiet while they considered the pictures my father was selling. After they left, my mother would yell “The coast is clear!” and we could come out of our rooms and relax.

“The pressure of always putting on a show for those people really got to my mother. She was a person who hated snobbism and had that direct Dutch character of always stating her opinion. Her personality was in a way like Dutch weather. The clouds in Holland sometimes block out the sun, sometimes let it shine through. Different moods for different times, and you had to be prepared for both. My parents divorced in 1970.

“I never saw my mother dance, and, as the years went by, she talked less and less of her dance career because it belonged to a world that existed in the distant past. It was nice to go to the ballet with her, though, because she would occasionally comment on the dancers’ moves. ‘Oh, that was off!’ ‘Oh, that’s good!’ It was like being at a basketball game. Balanchine became simply one of the men who came to our house to play bridge and gin rummy with my father, along with the pianist Vladimir Horowitz and the cellist Gregor Piatagorsky.”

After being captured by two very disparate popular artists–Weegee and Hirschfeld–in the forties, Franca sat for a pair of portraits by the Dutch Fauvist painter Kees van Dongen. Salz believes that his father commissioned the pictures in Deauville in the mid-fifties. The stronger of the paintings–Portrait of Marina Salz–seizes the vivid energy intimated in the meager but telling accounts we have of Franca. Serendipitously, the public will be able to view this image May 4-8 at Sotheby’s (1334 York Avenue at 72nd Street, New York City), where it will be offered in an auction of Impressionist and Modern Art on May 9.

Salz prefers not to dwell in print on the last phase of Franca’s life, which was dark, plagued by deteriorating health and spirits. For publication, he reports simply, “During the seventies, my mother had a ninety-acre country estate in Bedford, Pennsylvania, which she helped create with her new partner, who was Russian. Together they named the place Swan Lake. My mother died there peacefully in 1999.”

Franca’s son has proffered his information in the hope that his mother will be remembered. By strange coincidence, this addendum is being posted on the 90th anniversary of her birth. Far be it from me, then, to deprive Salz or Marina Franca herself of the Heaven-bent apotheosis that ballets of the past deliver so generously.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias