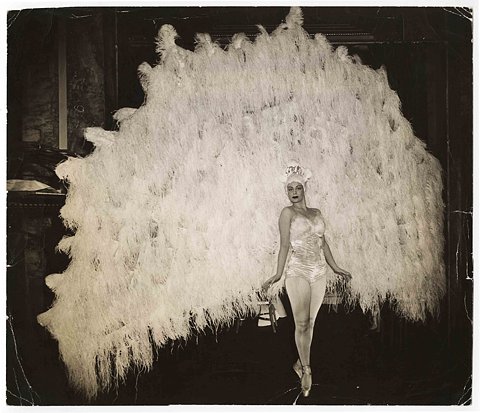

A press release arrives, announcing an exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York. Titled Unknown Weegee, the show runs from June 9 through August 27, 2006. It’s culled from ICP’s vast collection of images–over 18 thousand–made chiefly in the 1930s and ’40s by the tabloid photographer Arthur Fellig (1899-1968), best known by his moniker, Weegee. The announcement is illustrated with the strange and striking shot you see here. In this early release, the figure is not identified; the photograph is enigmatically captioned Cinderella Ball, 1941.

Weegee

Ballerina Marina Franca in her peacock costume, April 18, 1941

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee / International Center of Photography

When we look at this image today, we see double: The woman is both a symbol of classical dancing, old style–Odette with her ruff of feathers at the hip–and the iconic Vegas showgirl we can conjure up in our mind’s eye, though we’ve never been to Vegas.

Typically, Weegee captures his subject mercilessly in garish light. A crime photojournalist by trade and temperament, he pretends to do no more than document brute surface reality–the bleeding corpse lying in the gutter, with the cops forming an ironic honor guard around it. In this and his other modes, such as his portrayals of working class folks, down and outs, or victims of disaster and their avid oglers, he cannily provokes our imagination to create the story behind the image. He makes us see.

He also makes us think. Contemplating this lady in her outlandish white costume–all shimmer and froth–we wonder: Who is she? How did she arrive at this time and place? This peculiar destiny? What does her “performance” consist of? Is she, perhaps, a reluctant collaborator in her work? He also makes us dream.

Several ingredients stir our imagination. First, the woman as bird, a transformation replete with mystery and transgressive suggestion. Then, the ambiguities and metaphors that abound in the display. The prodigious “tail” of the costume is unfurled like a peacock’s, but it suggests swan’s-down in its softness–and purity in its whiteness.

The extravagant appendage–how could the woman move in it?– frames her like a cumulus cloud or a parachute gently collapsing as the figure it transports descends from air to earth. It seems not so much attached to her frame as part of her anatomy–an odd, marvelous extrusion like the wings of a goddess or fairy.

The image also conjures up associations that are more mundane, though they are, themselves, based on our addiction to the fanciful: purebred Angora cats painstakingly fluffed out to cop the blue ribbon for being Best in Show; yesteryear’s mannequins and movie stars cradled in lavish bubble baths; socialites enveloped in ostrich feather cloaks.

One way or another, the figure in the picture was surely meant, in its context, to be at once desirable and unattainable, an impossible dream.

Wait a minute. These flights of fancy are sheer fiction. Photographs are rooted in reality. This woman was real, and, though her situation remains ambiguous, evidence indicates that she was a classical dancer–if, perhaps, one fallen on difficult times.

Just look. Her ballet training couldn’t have been negligible. Her body is well acquainted with turnout. Hers is not generous, but it’s solid. The thighs are firm. The knees are taut. The feet, small and nicely shaped, are well placed in neat fifth position sur les pointes. The middle of the body is thick and inarticulate by today’s strict standards, matronly as opposed to the adolescent look that is now classical dancing’s female ideal. Yet old photos tell us that, in the lady’s own day, figures like it were admired, both on stage and in society. The legs are discouragingly robust, but the head is a classical dancer’s head–close enough to beauty to pass for it. Its poise on the neck is elegant, and the face is eminently readable.

A critical clue turns up in another ICP dispatch–an alternative caption: Ballerina Marina Franca in her peacock costume, April 18, 1941. Well, a tabloid is likely to call any dancing female a “ballerina,” but maybe . . . I’m a dance writer. This mystery is for me.

I scan my bookshelves. They harbor many an out-of-print book bursting with information about ballets and dancers no longer considered “important” enough for inclusion in latter-day roundups. Grace Roberts’s The Borzoi Book of Ballets (Alfred A. Knopf, 1947) gives first casts of the works it describes. It reveals that Franca was in Léonide Massine’s 1938 creation-of-the-world ballet, The Seventh Symphony, as the female Deer, with George Skibine as her cervine mate, and Bacchanale (1939), in the chorus of Nymphs. In Marc Platoff’s 1939 American West ballet, Ghost Town, she played an actress called “La Menken,” who is apparently a diva. From Roberts’s evidence I gather that Franca’s province was small featured roles. She may well have become accustomed to outré costumes in these ballets, which featured designs by Christian Bérard, Salvador Dali, and Raoul Pène du Bois, respectively.

Still operating from home, and, thanks to Roberts, knowing the milieu Franca flourished in, I consult Jack Anderson’s The One and Only: The Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo (Dance Horizons, 1981). Marina Franca’s name appears in a paragraph that includes more illustrious ones: Alexandra Danilova, Alicia Markova, Nathalie Krassovska, Mia Slavenska, Milada Mladova, Nini Theilade. I phone Jack, hoping to find out more. He says, “Ask Freddie.”

I’m lucky to have a slight acquaintance with Frederic Franklin, whom I admire enormously for his manifold contributions to the world of dance and his unquenchable sanguinity and charm. British born, he’s best remembered as the premier danseur of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, where he had a legendary partnership with Danilova. Today, having recently celebrated his 92nd birthday, he is staging, coaching, even performing. In American Ballet Theatre’s 2006 season at the Metropolitan Opera House, he has been cast as the Charlatan in Petrushka, Friar Laurence in Romeo and Juliet, and the Tutor in Swan Lake, the last role one he plays so subtly and astutely, it makes Siegfried look momentarily unimportant.

I phone “Freddie,” who has this to say about Franca: “Massine engaged her. In 1937 he went around everywhere to collect dancers. I think he must have found her in Preobrajenska’s studio in Paris. She was a soloist, though she did corps work as well. She was a very good dancer–strong, solidly built, not the willowy sort. Her type was demi-caractère, which Massine favored. And Massine liked her very much. Her technique was above average and she was a strong personality on stage. Even offstage she went over the footlights. She was the personality girl.

“I always thought she was Dutch or German or something. Her English was very good. We never got to know each other personally. We were 55 dancers in that company. We just did our shows and got on the train for the next stop on the tour.

“She joined us in 1938 for our season in Monte Carlo. Next we went to London. Then we got on a ship for the United States, where we played 110 cities. After we were back in Europe, the war broke out and in that turmoil we lost many of our European dancers. We never saw Marina Franca again. Amongst ourselves, we never talked about her afterwards. I don’t know what became of her.

(Laughing) “I can’t imagine that the costume you describe her wearing in the Weegee photograph had anything to do with the Ballet Russe.”

Having been trained as an academic, I next took my curiosity to the library. Specifically to the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, which harbors the most comprehensive collection of dance materials in the United States.

The results were meager–two items. One of them was a Marina Franca clipping folder. This contains a couple of photos of the dancer reproduced in the New York Sun and the New York Post in 1938, in conjunction with a Ballet Russe engagement at the old Met. If there was a text attached to them, it’s been sheared off. Next to these lies an unsigned typescript (from the pre-computer, Courier-font era) that calls itself a “bio.” It devotes 17 of its 38 lines to an anecdote about the dancer’s being arrested, wrongly, in Monte Carlo, on kidnapping charges involving a Russian youth she’d met in Paris. More usefully, it confirms Franklin’s belief that Franca was Dutch, reveals that she was born in 1918, left Holland because ballet essentially didn’t exist there, and studied in Paris with Egorova, making a detour to Preobrajenska for the perfection of her fouettés. Beyond that it tells us only that she toured “the Continent” with Lifar and danced at the Paris Exhibition before hooking up with Massine.

The second item is more rewarding–a sheaf of photographs, 32 in all, none of them by Weegee or, for that matter, by any photographer whose imagination reached beyond the confines of the studio publicity shot. Still, there is much to be learned from this evidence.

The photos, every damned one of them undated, seem to extend from a pre-Ballet Russe period through Franca’s brief sojourn with that company. They capture the dancer in three modes: Glamour Personified, where she resembles the Hollywood movie stars of the period; Mischievous Temptress, where she offers an illicit eroticism that is neither deep passion nor high tragedy, but simply fun; and, with make-up reduced, Breath-of-Spring Ingénue. In a couple of the shots, two of the guises are deliciously coupled–the virgin and the vixen, for example. Franca knew how to look at the camera, she knew how to act for it, and makeup became her.

All the full-figure shots confirm the bulky legs, though one must remember that, in Franca’s day, the dance world had not yet made a fetish out of anatomy as it would do subsequently. One image reveals a back so supple and eloquent, one would forgive its owner many a flaw.

Needless to say, the net of Google snared nothing about Franca. She was before its time.

And there my evidence ends. A more thoroughgoing and wide-ranging investigation might yield further information, but life is too short and my other interests and obligations too demanding to indulge myself further in tracking Franca. What’s more, by now I have, just through my modest search, learned the lesson inherent in the lady’s vanishing. It’s this: Despite all the worthy efforts of preservationists, dancing is ephemeral. It exists most powerfully in the here-and-now presence of witnesses. Its next realm is memory, which inevitably fades with the years and the passing of generations until it’s no more than hearsay. Eventually it disappears almost entirely, leaving tantalizing traces like the perfume of a beautiful woman, which lingers for a time after she has left the room.

© 2006 Tobi Tobias