This article originally appeared in Tutu Revue.

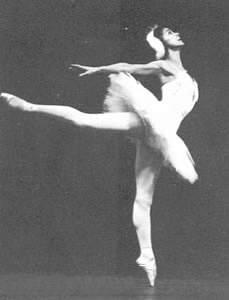

Marie Taglioni as the Sylphide

There’s a subdivision of feminist thinking that condemns the beloved storybook ballets of the nineteenth century for their ostensible political incorrectness. All those sylphs and Wilis, it maintains, all those maidens suspended in states of enchantment represent women as frail, vulnerable creatures, deprived of power over their own destinies, the victims–often in the name of love–of dominant men.

I think it’s absurd to apply sociological convictions and agendas to aesthetic creations–particularly when it comes to the sociology of one era and the art of another. It’s even more wrong-headed, surely, to argue the case from inaccurate observation. Examine, as I’m about to do here, the heroines and their sister protagonists (foils, alter-egos, even villains) of a half-dozen evergreen ballets from the Romantic and Classical eras and you’d be hard put to find a spineless female among them.

Consider first La Sylphide, which set the tone of Romantic ballet. Though she appears exquisitely fragile and defenseless, a creature of gossamer and mist, the Sylphide is one dangerous lady. She’s as amoral as the workings of nature; her mercurial temperament–tears one moment, ecstatic joy the next–is like changing weather. She loves James–indeed, as she relates in a mime passage now regrettably omitted in some productions, she has been watching him since he was a little boy, stalked him when, as a young man, he hunted in the forest.

Free from a sense of responsibility for her actions, impervious to guilt based on an awareness of others’ feelings, the Sylphide reasons: If I desire him, he should be mine. This is the simple narcissistic logic of a child, untamed by civilization. The Sylphide’s ingenuous offerings to James–the wild strawberries, the bird’s nest with its delicate cargo, the spring water she cups in her hands, rushing with it on tiptoe to her beloved–are as impulsive and impractical as a kindergartner’s and equally willful.

Nina Ananiashvili as the Sylphide

We domesticate our children to keep them from ravaging the social fabric. The Sylphide is a creature who has escaped this process; she runs beautiful, wild, and free–destroying everything in her path and herself as well. One may pity her in her poignant death throes. Yet she has contributed to her own undoing, coveting the secretly poisoned scarf with which James pinions her as if it were a tantalizing toy that was her due–just as she coveted James. Surely everyone in the ballet, to say nothing of its audience, would agree that this figure is hardly weak or passive, but rather a force to contend with.

The role of the other important woman in La Sylphide–the witch, Madge–is often played by a man, and to great effect (think Erik Bruhn, think Niels Bjørn Larsen). But the character is female, and an icon of terrible strength. Clad in dirty rags, warming herself at other folks’ fires, earning her tot of whiskey by telling fortunes, Madge masquerades as one of the powerless. When she first infiltrates James’s house, she appears to be a pitiable old woman–crippled, poverty-stricken, without a hearth to call her own.

Kirsten Simone as Madge

Courtesy Royal Danish Ballet

© Martin Mydtskov Rønne

Deprived as she is of life’s material necessities as well as any kind of social standing, she seems to be harmless. At best she’s an object of her community’s indulgence and charity. Her thoroughgoing impotence turns out to be a canny disguise. Taking her revenge for a casual insult, she ruins both James and the Sylph–in other words, the poet and his vision.

Effy, James’s betrothed, deserves consideration here too, though she’s only a secondary character in the ballet. She displays a kind of staying power common to women: She accepts life’s blows and makes do. At first, when James, choosing to follow his dream, jilts her (and the snug domestic milieu she represents), Effy behaves as if felled by tragedy. Act I of the ballet closes on a tableau of her utter despair.

Midway through Act II, however, she regains her equilibrium and turns sensible before our very eyes. Recognizing the impossibility of recovering her true love, she thinks things over and, with sweet resignation, agrees to marry her other suitor, Gurn. He’s a nice ordinary fellow, undistracted by illusions, who will provide her with a settled life warmed by his devotion, children (humankind’s instinctive bid for immortality), and the small, quiet joys of the commonplace.

In no way can he replace James in Effy’s imagination; he’s a character dancer, after all, not a danseur noble. Gurn represents mere reality, and Effy has the good sense to accept this as the best choice remaining to her. It’s not an ignoble one. It allies her with legions of women whose unsung heroism consists of a steadfast consent to what life has offered them.

Galina Mezentseva as Giselle

Now think of Giselle. Granted, its heroine at first epitomizes the kind of innocence that so often guarantees its own undoing. Giselle allows herself to be taken in–seduced, if you will–by Albrecht, one of those aristocrats who amuses himself by going slumming amidst the local peasantry. Depending upon the reading a particular production and its leading dancers give to the libretto, Albrecht may be truly in love with the unworldly girl. Still there’s no denying that Giselle is the victim of his deceit and that he fickly betrays her when confronted by his fiancée, Bathilde, and the full force of the court that is his “proper” social sphere.

Even in Act I, however, Giselle demonstrates considerable self-assertion. She steadfastly rejects the persistent courtship of Hilarion who, within their social circle, is the logical match for her. And she subverts her mother’s orders not to tax her weak heart by dancing, which to her is not merely joy but necessity. In other words, she persists in following the dictates of her own needs and desires despite the pressures of the confined world in which she dwells.

Joanna Berman as Giselle

In Act II, Giselle becomes strength incarnate, emerging from beyond the grave, a wraith not yet leached of human feeling, to rescue her unfaithful lover from the death sentence of the avenging Wilis. Giselle’s victory here is a triumph of the pure spirit impelled by sheer volition.

Alla Sizova as Myrtha

Olga Spessivtseva

as Giselle

The power of Myrtha, the implacable queen of the Wilis, is unambiguously superhuman, so perhaps this figure doesn’t earn a place in the pantheon of feminist role models. Still, the character can be understood as a metaphor for women who go into battle for a cause, impelled by rage (just or unjust) and nearly impervious to defeat because their entire being is focused on their single-minded conviction.

Margot Fonteyn as Odette

In Swan Lake, the White Swan and the Black Swan, Odette and Odile, respectively embody the power of sublime good and monstrous evil. Odette, despite her lamentable situation–she’s a princess doomed to captivity, deprived even of her human form–is not entirely defeated. First she protects her sister prisoners against the hunters who see the magnificent white birds as their legitimate prey. Then she pleads her case with their leader, Prince Siegfried, so eloquently that his sympathy escalates into a pledge of love and commitment. Once the hope he holds out is sabotaged, she has the courage to end her own life.

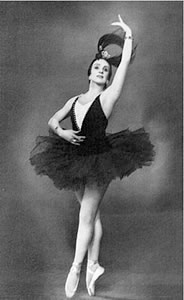

Natalia Dudinskaya as Odile

Odile, scion of the evil sorcerer von Rothbart, is clearly her father’s daughter, reveling in her ability to annihilate any manifestation of purity, beauty, and trust. She’s even more potent a threat than von Rothbart, since she adds erotic power to her dad’s arsenal. It’s not that she wants Siegfried; she wants Siegfried destroyed, along with the very essence of Siegfried’s bond to Odette.

Once psychology was widely accepted as a science, ballerinas performing the dual role of Odette-Odile began to comment that they saw the two personalities as different aspects of a single character. The notion has proved useful. Legend, as well as much literature and film of the past, often made its effect by contrasting monolithic types–the good girl versus the bad girl. The idea that every more or less good girl contains a healthy portion of bad girl impulses (and vice versa) allows for a welcome richness of character and behavior in female heroes and villains. It helps today’s ballet-goers, who may be leery of old-fashioned fantasy, identify with the imaginary figures who populate yesteryear’s landmark works. It gives us a way in.

Irina Dvorovenko as Odette Courtesy American Ballet Theatre © MIRA

Swanilda, the heroine of Coppélia (Coppélia, you’ll recall, is the mechanical doll), is memorable first for her delicious temperament. She’s effervescent, the possessor of a joie de vivre so ebullient, it spreads itself over the stage, making the whole ballet radiant with happiness. There may be no more powerful gift than this.

Though this young woman’s a darling, that doesn’t keep her from being feisty. She’s as self-assertive as they come, quick to berate her boyfriend when he gets out of line, bowing and blowing kisses to the (almost) living doll in Dr. Coppélius’s window, falling, as so many hapless fellows do, for an inanimate pretty face. She even administers a quick scolding when her Franz catches a butterfly and impales it with a pin to serve as his boutonnière. (Perhaps she’s identifying with the butterfly and refusing to be anyone’s trophy.)

Jenifer Ringer as Swanilda Courtesy New York City Ballet © Paul Kolnick

The boyfriend, let it be noted, is unworthy of her. Oh, he’s charming, this Franz, but hopelessly doltish, and fickle besides. It takes a Swanilda, both courageous and clever, to save him from himself and claim him as her own. She braves Dr. Coppélius’s lair–the menacing laboratory of a half-crazed old man who dabbles in the dark mysteries of human life. She’s impelled by curiosity, a trait typical of an intellectually daring female. Once inside, having pluckily investigated the situation, she saves her boyfriend from having some vital part–heart? soul?–removed by the obsessed inventor who fantasizes transplanting the human anima into his otherwise perfect doll.

Like many a self-realized woman, Swanilda is not always likeable. She’s undeniably cruel to Dr. Coppélius–pretending to be his doll come to life, then mocking him as she exposes her ruse and his pathetic belief in (and love for) his creation. But her actions are necessary to the theme of the ballet, which celebrates the triumph of real human existence, with all its peculiarities and flaws, over the mechanical imitation of it, no matter how ingenious. And, once she has Franz safely in wedlock, Swanilda apologizes to the old man with the easy grace of those whom destiny has favored.

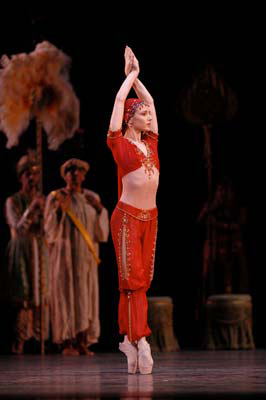

Alina Cojocaru as Nikiya

Courtesy American Ballet Theatre

© Marty Sohl

The Hindu-land melodrama La Bayadère also refutes the feminists’ complaints. It gives us the formidable Gamzatti–gorgeous, well-heeled, and well connected–who ruthlessly goes after what she feels is hers by rights (the hero) and gets it, though she doesn’t get to keep it. Admittedly, her opposite number, Nikiya, the ballet’s soulful, disenfranchised heroine, is thrice-victimized: by her rival, Gamzatti; by her lover, more resolute in war and tiger hunting than in his affections; and by the lust-corrupted priest in whose temple she serves as a dancing slave. It’s true, too, that in the Kingdom of the Shades scene, which is undeniably the heart of the ballet, Nikiya proves to be even lovelier–more touching, more desirable–in death than in life.

Stella Abrera as Gamzatti

Courtesy American Ballet Theatre

© Marty Sohl

Yet her very plight gives her enormous power. It moves the gods, provoking them to cause the most spectacular architectural catastrophe in classical dance, the destruction of the resplendent temple that buries every last member of the ballet’s sizable cast. The event also rewards Nikiya with a radiant apotheosis in which she and her beloved join hands in a realm of eternal bliss. Politically correct thinking, already stirred up by the slave-of-dance theme, will dub this afterlife payback equivocal. So be it. In its time and in its context of make-believe, it was satisfactory.

Student of the School of American Ballet as Marie

Courtesy New York City Ballet

© Paul Kolnick

If feminist polemicists are not convinced by these examples of ballet’s nineteenth-century heroines holding their own and then some, they might simply look to little Marie in The Nutcracker. Yes, she’s fearful and given to fainting when her space is invaded by rodents, one of them a royal menace with seven heads. Yes, she cedes the sword-to-sword combat with the enemy to her Nutcracker Prince. After all, she’s a typical well-brought-up child of the Victorian bourgeoisie, who knows the roles assigned to boys and girls, tomorrow’s men and women. But when the battle is going against her rescuer and cavalier, remember, it is she who has the canniness and fine aim to hurl her slipper at the enemy, distract his attention with her sure, sharp hit, and thus assure his downfall. When the child Prince recounts the story to the Sugar Plum Fairy and her court in the Land of Sweets, he gives Marie full credit for her prowess. And so should we.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias