Stars of the 21st Century / New York State Theater, NYC / February 14, 2005

Agrippina Vaganova’s showy Diana & Acteon pas de deux found American Ballet Theatre’s Xiomara Reyes, a pixie of a huntress, demonstrating how the body can represent at once bow, arrow, and archer, while her partner, Herman Cornejo (also from ABT) displayed the bravura technique, everywhere suffused with grace, that has catapulted him to the top echelon of today’s male dancers. Though he’s a stunning virtuoso, his performances have increasingly suggested a range and depth of feeling that might qualify him for the danseur noble category. He lacks only the height and princely good looks associated with that type; maybe it’s time to quit holding that against him.

Eleonora Abbagnato and Alessio Carbone drew the short straw when it came to choreography (though presumably the dancers had some say in what they performed). Their first number was a duet from Roland Petit’s L’Arlesienne, where the folkloric embellishments do nothing to conceal the lack of an authentic dance impulse. Though the material natters on endlessly, it never gets close to answering the question a baffled viewer might well pose: Is the soldierly gentleman’s problem conscientious objection or a more domestic difficulty that a dose of Viagra could resolve? (Neither, I found, after some post-performance googling, but, ripped from its larger context, the duet fails to tell its real story.) A second stymied offering, Mauro Bigonzetti Kazimir’s Colours, proved to be an exercise in angularities and gymnastic coupling, with little air allowed between the two bodies. The attempt to evoke Kazimir Malevitch and the abstract geometry of that painter’s Suprematist style, was surely a foolhardy undertaking; given the nature of the human body, the concept is impossible to convey. Nevertheless, being from the Paris Opera Ballet, the dancers executed both their assignments with an objective, impeccable purity that’s a phenomenon in itself.

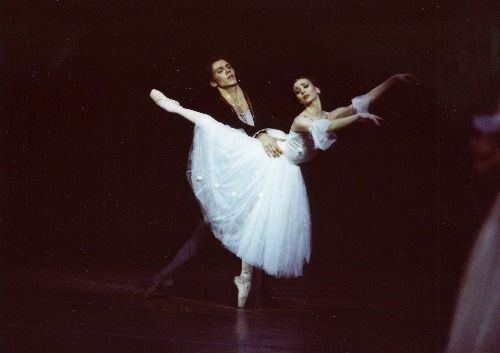

The celebrated partnership of the Royal Ballet’s Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg—she emerging as the most gifted ballerina of her generation; he the most sympathetic of partners—was showcased in the Act II pas de deux from Coralli and Perrot’s Giselle (which epitomizes the delicate, morbid, and sublime elements of Romantic dancing) and Petipa’s Don Quixote pas the deux (which demonstrates the fireworks element of the classical mode). I’ve had my say about this pair in these pages and their gratifying physical and emotional rapport. Just now, the much-feted Cojocaru needs to beware of exaggerating her effects in the gauzy Romantic style and to cultivate, if it’s in her, more of an appetite for the dazzling bravura feats she already commands. She can bring them off, all right, but she lacks the instinct for circus-style excitement.

Dancing the Rubies pas de deux from Jewels, Diana Vishneva and Andrian Fadeev, proved—if this still needs proving—that the Kirov Ballet can manage a reputable reading of Balanchine. Vishneva, in her effort to be echt American in the jazzy rhythms and free-flung moves, goes almost too far—yet the results suggest that she’s still imposing a Russian-school control on her material, simply at extravagant extremes. Fadeev, all boyish charm and correctness, must learn to burn brighter before he can accurately be termed a star, but he’s undeniably appealing. In the Balcony pas de deux—performed alas, sans balcony—from Leonid Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet (the granddaddy of the great R&Js), Vishneva was lovely if, as always, overly aware of the effect she wanted to make; Fadeev, again, a little too reticent. Both, though, deflected any serious complaint with the most beautifully shaped high-flying leaps imaginable.

The famous pas de deux from Le Corsaire teamed up the New York City Ballet’s Alexandra Ansanelli with ABT’s Angel Corella. Ansanelli is so petite and pretty, she can’t help simpering a little, but Corella, a virtuoso with a full complement of humanity to him, deserves more depth in a partner—and more technical precision. On this occasion some of Corella’s gasp-inducing feats looked a little forced, despite his irresistible combination of sunniness and wild-animal élan. Could it be that he has begun to grow insufficiently elastic for the murderous shenanigans? If ABT can’t provide him with roles to ensure his future as a mature artist, he might profitably consider going the Baryshnikov route. But I digress.

Munich Ballet’s Lucia Lacarra and Cyril Pierre received the evening’s heartiest acclaim, in two sensational numbers by Petit, whose forte is theatrically savvy melodrama: the bedroom pas de deux from Carmen and a pas de deux from La Prisonnière. Both items deal in poster-art eroticism, the latter as kinky as the Proustian situation on which it’s based. The dancers approached the material as if it were an exercise in style, and the results were duly effective, though I’ve seen realistic Carmens that were more moving. Needless to say, Lacarra’s exquisitely arched feet and fabulous leg extensions worked to great advantage in these assignments.

A pas de deux from Bournonville’s La Sylphide seemed to take place in two different countries as well as two different eras. The Bolshoi Ballet’s Svetlana Lunkina, costumed à la Marie Taglioni, evoked the nineteenth-century Romantic style that originated in France, dancing as if she were doing delicate embroidery. Her James, the National Ballet of Canada’s Guillaume Côté (a last-minute replacement for Lunkina’s scheduled Bolshoi partner), was a contemporary North American type—athletic in style, forthright in demeanor. Needless to say, the combination failed to transmit either the ballet’s scenario or its atmosphere, but each dancer had considerable charm in his own way.

For the first time, the Stars agenda admitted some modern dance—the powerful and poignant “Steps in the Street” section from Martha Graham’s 1936 Chronicle, staged by Yuriko for an eleven-woman ensemble of Graham pros. Perfectly structured, magnificently stark, forceful, and poignant, it was performed with just the right focus and fervor by the group, Stacey Kapalan at its head. Judging from its less than thunderous applause and the absence of the shouts that greeted the fouetté displays on the program, the Stars audience was underwhelmed, but at least it saw an alternative to its favorite mode.

There is no way to provide a meaningful finale for a smorgasbord event like this one because, in truth, it doesn’t add up to anything. This occasion concluded with something inaccurately called a défilé. After bows for each pair that seemed to milk applause readily awarded earlier and a comedy-of-errors presentation of some very pretty bouquets, the stars took turns crossing the stage with their most flamboyant feats. Don’t ask.

Photo: Nina Alovert: Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg in Giselle

© 2005 Tobi Tobias