Impelled by her unabashedly maverick imagination, Cathy Weis melds dance, video, and the fact that she has multiple sclerosis into haunting theater pieces. Village Voice 2/22/05

Archives for February 2005

Elisa Monte Dance; Configuration

Monte’s choreography is handsome and functional, but all her devices remain standard; on the Configuration program, only Harrison McEldowney’s “At the End of the Road” offered genuine joy and wit. Village Voice 2/22/05

RoseAnne Spradlin

I guess RoseAnne Spradlin has death on her mind. Village Voice 2/8/05

STAR TURN

Stars of the 21st Century / New York State Theater, NYC / February 14, 2005

Agrippina Vaganova’s showy Diana & Acteon pas de deux found American Ballet Theatre’s Xiomara Reyes, a pixie of a huntress, demonstrating how the body can represent at once bow, arrow, and archer, while her partner, Herman Cornejo (also from ABT) displayed the bravura technique, everywhere suffused with grace, that has catapulted him to the top echelon of today’s male dancers. Though he’s a stunning virtuoso, his performances have increasingly suggested a range and depth of feeling that might qualify him for the danseur noble category. He lacks only the height and princely good looks associated with that type; maybe it’s time to quit holding that against him.

Eleonora Abbagnato and Alessio Carbone drew the short straw when it came to choreography (though presumably the dancers had some say in what they performed). Their first number was a duet from Roland Petit’s L’Arlesienne, where the folkloric embellishments do nothing to conceal the lack of an authentic dance impulse. Though the material natters on endlessly, it never gets close to answering the question a baffled viewer might well pose: Is the soldierly gentleman’s problem conscientious objection or a more domestic difficulty that a dose of Viagra could resolve? (Neither, I found, after some post-performance googling, but, ripped from its larger context, the duet fails to tell its real story.) A second stymied offering, Mauro Bigonzetti Kazimir’s Colours, proved to be an exercise in angularities and gymnastic coupling, with little air allowed between the two bodies. The attempt to evoke Kazimir Malevitch and the abstract geometry of that painter’s Suprematist style, was surely a foolhardy undertaking; given the nature of the human body, the concept is impossible to convey. Nevertheless, being from the Paris Opera Ballet, the dancers executed both their assignments with an objective, impeccable purity that’s a phenomenon in itself.

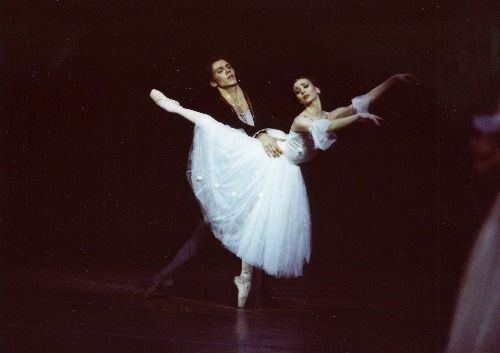

The celebrated partnership of the Royal Ballet’s Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg—she emerging as the most gifted ballerina of her generation; he the most sympathetic of partners—was showcased in the Act II pas de deux from Coralli and Perrot’s Giselle (which epitomizes the delicate, morbid, and sublime elements of Romantic dancing) and Petipa’s Don Quixote pas the deux (which demonstrates the fireworks element of the classical mode). I’ve had my say about this pair in these pages and their gratifying physical and emotional rapport. Just now, the much-feted Cojocaru needs to beware of exaggerating her effects in the gauzy Romantic style and to cultivate, if it’s in her, more of an appetite for the dazzling bravura feats she already commands. She can bring them off, all right, but she lacks the instinct for circus-style excitement.

Dancing the Rubies pas de deux from Jewels, Diana Vishneva and Andrian Fadeev, proved—if this still needs proving—that the Kirov Ballet can manage a reputable reading of Balanchine. Vishneva, in her effort to be echt American in the jazzy rhythms and free-flung moves, goes almost too far—yet the results suggest that she’s still imposing a Russian-school control on her material, simply at extravagant extremes. Fadeev, all boyish charm and correctness, must learn to burn brighter before he can accurately be termed a star, but he’s undeniably appealing. In the Balcony pas de deux—performed alas, sans balcony—from Leonid Lavrovsky’s Romeo and Juliet (the granddaddy of the great R&Js), Vishneva was lovely if, as always, overly aware of the effect she wanted to make; Fadeev, again, a little too reticent. Both, though, deflected any serious complaint with the most beautifully shaped high-flying leaps imaginable.

The famous pas de deux from Le Corsaire teamed up the New York City Ballet’s Alexandra Ansanelli with ABT’s Angel Corella. Ansanelli is so petite and pretty, she can’t help simpering a little, but Corella, a virtuoso with a full complement of humanity to him, deserves more depth in a partner—and more technical precision. On this occasion some of Corella’s gasp-inducing feats looked a little forced, despite his irresistible combination of sunniness and wild-animal élan. Could it be that he has begun to grow insufficiently elastic for the murderous shenanigans? If ABT can’t provide him with roles to ensure his future as a mature artist, he might profitably consider going the Baryshnikov route. But I digress.

Munich Ballet’s Lucia Lacarra and Cyril Pierre received the evening’s heartiest acclaim, in two sensational numbers by Petit, whose forte is theatrically savvy melodrama: the bedroom pas de deux from Carmen and a pas de deux from La Prisonnière. Both items deal in poster-art eroticism, the latter as kinky as the Proustian situation on which it’s based. The dancers approached the material as if it were an exercise in style, and the results were duly effective, though I’ve seen realistic Carmens that were more moving. Needless to say, Lacarra’s exquisitely arched feet and fabulous leg extensions worked to great advantage in these assignments.

A pas de deux from Bournonville’s La Sylphide seemed to take place in two different countries as well as two different eras. The Bolshoi Ballet’s Svetlana Lunkina, costumed à la Marie Taglioni, evoked the nineteenth-century Romantic style that originated in France, dancing as if she were doing delicate embroidery. Her James, the National Ballet of Canada’s Guillaume Côté (a last-minute replacement for Lunkina’s scheduled Bolshoi partner), was a contemporary North American type—athletic in style, forthright in demeanor. Needless to say, the combination failed to transmit either the ballet’s scenario or its atmosphere, but each dancer had considerable charm in his own way.

For the first time, the Stars agenda admitted some modern dance—the powerful and poignant “Steps in the Street” section from Martha Graham’s 1936 Chronicle, staged by Yuriko for an eleven-woman ensemble of Graham pros. Perfectly structured, magnificently stark, forceful, and poignant, it was performed with just the right focus and fervor by the group, Stacey Kapalan at its head. Judging from its less than thunderous applause and the absence of the shouts that greeted the fouetté displays on the program, the Stars audience was underwhelmed, but at least it saw an alternative to its favorite mode.

There is no way to provide a meaningful finale for a smorgasbord event like this one because, in truth, it doesn’t add up to anything. This occasion concluded with something inaccurately called a défilé. After bows for each pair that seemed to milk applause readily awarded earlier and a comedy-of-errors presentation of some very pretty bouquets, the stars took turns crossing the stage with their most flamboyant feats. Don’t ask.

Photo: Nina Alovert: Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg in Giselle

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

OTHER PEOPLE’S “GATES”

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: The Gates, Central Park, New York, 1979-2005 / February 12-27, 2005

The Gates, which I wrote about last week, will begin its vanishing act on Monday (February 27). This weekend offers a last chance to visit Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s installation—for the first time or once more. Following are a few of the observations I’ve received from AJ readers.

On the opening Saturday I spent about two hours walking uphill and downhill, sitting, musing, and wandering “aimlessly” in and around the central “third” of the park, listening at the same time to the Metropolitan Opera’s live broadcast of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro. The experience was exquisite, exhilarating. Sunday I spent another hour down on the first “third” of the park, with no music and far too many people, just hordes . This trip was nice enough, but over-“civilized.” It reminded me of visiting the World’s Fair grounds when I was a kid. Another day, at the top of the park: snow, ponds, ducks, waterfalls, woods, Telemann and Bach. Glorioso! In his appreciation of The Gates in the New York Times, Michael Kimmelman wrote, “Art is never necessary. Art is merely indispensable.” Whether The Gates is “art,” Art, or whatever, matters only to those who like neat pigeonholes and hierarchical thinking. At its best, it certainly provides an aesthetic experience. Best to me is when there are clusters of gates, winding and crossing pathways, flying skirts, moving people, and great music in my ears. —Jane Remer

The Gates reminds me of how marvelous it is to be a “bodied” species (unlike the floating minds on Star Trek). Dance-minded people simply experience the world with a unique set of faculties, as your piece points out. Children demonstrate this when they use their own form as a measurement device. Watch them walk down the stairs and you will often see their hand stroking the wall. Line them up and witness their urge to bump into the person in front of them and the one behind them. Physical contact with objects tells them where they end and the world begins. Sounds like your granddaughter enjoyed The Gates with an eye for the fact that it’s her body that makes the project fun. —Nancy Galeota-Wozny

I went up to the park Sunday night at eleven o’clock and walked for two hours through the falling snow and swirling winds, till my feet were too cold and wet to continue. I let myself get completely lost—dogged, plodding, enchanted. I don’t know the park well, and I’m not at all sure where I went. I saw the bronze poets, with snow heaped up on their shoulders, and the shuttered Delacorte Theater, and a sort of rustic chalet. I wound west and east and up and down from Columbus Circle to East 72nd and then finally over near the Museum of Natural History, and back down again to Mr. Columbus, moored in his barren plaza.

The Gates reveals a whole side of itself at night, and in the snow, that I didn’t see on the crowded weekend mornings when I visited it before. The particular choice of color suddenly makes even more sense than it does when read by day against the dun and gray of the February trees and earth. The street lights cast a pale orange glow, and, as it spills onto the falling and fallen snow, the light appears to emerge and spread out from the gates themselves. And the lanterns around Tavern on the Green are exactly the color of the fabric, magically condensed. The snow and wind make wonderful noises on the fabric. The snow was falling so thickly that it had time to build up a little on the gates’ wildly flapping skirts sometimes; then, when the wind suddenly died down, the snow would slide off all at once with a dry little swoosh.

There were other people out too—few, but some—doing the same thing I was doing. Couples, gay and straight, walking arm in arm or hand in mittened hand. A stocky guy with a big camera wrapped in plastic, leaning against a gate leg to steady his cold hands for a long exposure. Little groups of friends. People playing with a dog that raced in circles, spraying snow up behind his heels. Boys on bicycles. A lady with bright green hair who smiled and said, “Aren’t we lucky?” A stoned girl frantically trying to relight her pot pipe with a lighter, who asked, “Do you have any matches?” and then, “So would you call this performance art or conceptual art?”

The gates make you want to just walk and walk and not stop. To me, they look as though they’re walking themselves, striding through the park on their spindly orange legs, with their perfectly pleated skirts fluttering and flapping, and stomping around in circles with their gray, pachydermal iron feet. I loved the way the snow built up on every horizontal surface they offered, down to the tiny self-locking nuts near the bases.

The snow piled up on me too. By the time I left the park, my clothes were crusted all over. Descending into the subway to ride home, I realized that miniature snowdrifts had accumulated on my beard and eyebrows too, as I felt the snow begin to melt, cold water flowing down over my eyes and cheeks and chin. —Christopher Caines

GATED COMMUNITY

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: The Gates, Central Park, New York, 1979-2005 / February 12-27, 2005

How could I not be interested in The Gates? That pair of canny, visionary (oh, let’s call them) artists– born on the same day in 1935, one in Bulgaria, one in France, New York City denizens for over four decades–installed it in my backyard. And, what’s more, made sure it would appeal to a dance person. For it’s an artifact that, though you can scan it with pleasure (or antipathy) from outside or above, requires you to walk through it, walk in it, your pacing feet measuring time and space, if you’re to experience it truly.

Backstory:

http://www.christojeanneclaude.net/

http://www.nyc.gov/html/thegates/home.html

“The Gates” in online archives of the New York Times

As the press has been telling us unremittingly, The Gates consists of 7,500 orange portals, each with a swath of orange fabric hanging from its lintel, that have been placed along a marathon 23 miles of Central Park’s pedestrian walkways–from 59th Street to 110th Street and from Central Park West to Fifth Avenue.

I started walking The Gates almost daily during the week in which the portals were being installed. They are arranged in batches of irregular numbers. I encountered groups containing as few as two, as many as 21. People assiduously tracing the full 23-mile extent of the installation and focusing on the numbers will find, published stats tell us, as many as 36. The occasional singletons I came upon felt like accidents, because the project as a whole makes a major part of its impact through repetition. This repetition, as you tread The Gates’ paths, deftly turns footfall into drum- or heartbeat. Martha Graham used the same steady-pulse phenomenon in the formally paced entrances and exits that frame the sections of her Primitive Mysteries. Laura Dean, choreographing to the music of Steve Reich, made it the keystone of her contribution to postmodern dance.

I found that one portal was usually about five paces distant from the next, according to my stride (yours may well be different). In many–perhaps all–of the groups, the portals are, indeed, equidistant, except where they’ve been nudged a little by foliage that has scrupulously been awarded the right of way. In some groups, though, the spacing is about ten or 15 of my paces. Between the groups lie stretches of negative space–about 12 feet long, according to the stats. These “gaps” are energized by the groups of gates that precede or follow them on the same path.

The portals are all the same height–16 feet. They vary in width–five and a half feet to 18 feet–according to the width of the path they bestride. Because of the other aspects of uniformity the portals share, you don’t notice (at least I didn’t notice) that significant variation in width for an astonishingly long time. On a particularly narrow walkway, I could stand in a portal and, stretching my arms sideways, touch its sides. My seven-year-old granddaughter, who has accompanied me on several of my treks, longs to do this, and keeps trying, but can’t manage it yet. Just think, children must feel this way all the time.

According to the terrain, the groups of gates promenade in straight lines or swerve into gentle curves. When two paths converge, the two lines of gates veer off from each other at odd, disconcerting angles. Similarly, scoping the park from any vantage point in the course of your promenade, you see series of portals from different angles. Walking past–not through–a group at a certain distance, you can see the angles of the portals shift as your place in space shifts in relation to them. Herein lie lessons in perspective, both objective and metaphoric.

Dance observers will recognize The Gates’ tactic of combining repetition and surprise. Balanchine used it all the time.

The gates proceed, orderly and calm, up and down gentle inclines. Any series of them can be said to ascend or descend. Their up or down inclinations depend on the direction the walker or viewer dictates.

One line of gates marches up to a decrepit path-striding wooden trellis covered with gnarled wisteria vines. Another leads away from it. The tall, shiny, new, boldly orange structures seem to stop and leave some empty space in deference to the rough-hewn, dull brown bit of carpentry, as if they knew that the trellis becomes an enchanted gazebo of leaf green punctuated by lavender when the vine blossoms in the spring, and that its life, though modest in impact, has been long and will be longer. In myriad ways like this one, The Gates, though it invades the nature-sanctuary aspect of the park, gives the park back to its users. Through its blithe intrusiveness, it reawakens the observer to the more recessive and far more profound attributes of tree, earth, water, and stone.

I’m convinced that this project has wit. Consider this: Most of the gate groups are open-ended; the one dead-end installation I’ve encountered thus far stops at a playground. Moral: If you can’t forge ahead, stop to play. Elsewhere, a group of four gates marches up to another playground via a tiny flight of steps.

At every break in the low stone wall that encloses the park–these openings were called “gates” by the park’s original designers, hence the name of the current project–the orange portals line the entry paths like carnival shills, luring passersby to take in the larger show.

The portals’ hue (a mellow orange, sliding toward peach) matches–has anyone else noticed?–the webbed feet of the park’s duck population. The fabric, by contrast, is exclamatory (or caution) orange, as in Orange Alert (a familiar state in this town). Everyone is calling both colors “saffron,” which is inaccurate though elegant and evocative. Some are comparing the color to the brazen copper-shot crimson of Jeanne-Claude’s hair. This is simply wrong. The two-tone orange of the fabric-festooned portals offsets the somber browns, greens, and grays of the winter landscape, which is all “That time of year thou mayst in me behold / When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang / Upon those boughs that shake against the cold, / Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.” Sun sets the gates aflame.

One misty afternoon, the seven-year-old decides to practice tightrope walking on the wooden fences that line the car path. It’s only a three-foot fall and there are no cars in sight. Suddenly an imposing limo comes cruising toward us, but slows to a cautious crawl as it passes the child, and in it we glimpse (unmistakable with that hair and now well-publicized, handsomely ravaged face) Jeanne-Claude. “Hello,” I yell, waving. “Thanks!” The child continues her tenuous balancing act, undistracted by issues of fame and the serendipitous coincidences that characterize life in New York.

Each gate is a door frame, welcoming you as you “enter.” Each sends you out into another world. Unless you decide to stay, undecided–and you’re welcome to–the in/out process is accomplished in a matter of seconds.

The dates in the project’s full title indicate the years elapsed from conception to (hard-won) realization. The actual life of the installation is shorter; after 16 days, it will vanish. The ephemeral nature of the thing is an essential part of it. In this, too, it is related to dancing.

As I said, this thing has been planted in my back yard. I live on the Upper West Side, half a block from the Gate of All Saints at the park’s 96th Street transverse. The morning of the project’s official opening, when the fabric is unfurled from its overhead cocoons, I’m out there in the freezing damp among some 100 neighbors armed with friends and lovers, offspring, cardboard coffee cups, and cameras–witnessing. All the previous week, alone or with a child, I had watched the construction, the most thrilling element of which was the swinging of a gate from a horizontal position on the asphalt (passive, recumbent) to a vertical stance, a small, cheeky salute to the sky. I believe this was my younger granddaughter’s favorite aspect of the project. Just turned five, she is still relatively immune to the postmodern aesthetic but has long harbored career plans that favor the manual-labor trades.

When the bright rectangle of ripstop nylon first emerges from its coiled confinement–the fabric giving a faint whoosh, the heavy cardboard tube around which it was rolled hitting the asphalt with a hearty thwack–it’s tightly pleated, like the skirt of a parochial-school girl. As the days go by, the sharp creases will soften, allowing billows and similar freedoms of expansion into space. The progress is like that of a newborn infant slowly relaxing from fetal position in the course of its first few weeks.

The hem of the fabric–seven feet off the ground–seems to graze a tall grown-up’s head; half-grown kids stretch up an arm, expecting to touch it. Toddlers and kindergartners, hoisted on parental shoulders for their tour of the site, swipe plump hands at it with glee. Lanky middle-school boys with basketball dreams leap up at it, one arm raised, as if to slam-dunk a dark orange ball through a hoop in the air.

The next day is fair, balmy for the season. Natives and tourists turn out in great numbers to trace The Gates’ paths. New York has always rewarded walking, and the project has only enlarged that opportunity, transforming the place into Pedestrian City. Central Park has become the town square, with people promenading at a leisurely pace, chatting as they take in the scene around them.

The people walking through The Gates become part of it, in two ways: through their visible presence and through their individual perceptions of it.

Entering at Central Park West and 106 Street, you clamber up eight tiers of steps bordered by boulders, gates brightly poised on either side of each landing. At the top, you’re greeted by a goodly number of gates deployed on the periphery of a huge circle, the fabric waving in the breeze like a civic arrangement of celebratory flags. Just past this point you reach the spot’s highest prominence–called the Great Hill, but in truth a modest elevation–from which you gaze down through thickets of branches glinting silver in the afternoon light to see smaller parades of flags, tracing other byways. Downtown, the Great Lawn offers an even grander curved formation, but the larger expanse of the ground encompassed diffuses the enthusiastic nature of the effect slightly. Or perhaps the power of the impression depends on which location you happen to see first.

The circular configurations manifest a mood of triumph, elation; they’re an image of victory earned, joy deserved. You don’t necessarily need to trace their path with your feet to receive their message; most of it is delivered if you’re just standing still at a single vantage point, gazing at them. But these formations are the least typical aspect of the project. When, as happens most of the time, the flags line a path that’s fairly straight, despite some deviant undulation, the strategy gives the walker a sense of proceeding, of going somewhere, of setting one’s foot on the path of one’s destiny (or, at least, destination).

At every turn, The Gates claims a partnership with nature. Time of day and the angle of the sun affect your perception of the project. Looking across the Lake, from the east side to the west, as the sun begins to set, you see on the already darkening shore the flags gleaming faintly like distant torches. As the sun sinks further and hits other panels dead on from behind, they become rectangles of sheer glow, hearths to which one can return after a journey out in the wet, the cold, and the dark. Weather is significant, too, especially wind, which energizes the fabric panels. High wind makes them wild, heralds of violence. A breeze, rippling sideways through them, creates an undulating pattern of shadows. When the air is calm, the panels act like scrims, displaying the silhouettes of the neighboring trees, complex networks of branch and twig.

At 72nd Street, there’s a long, long stretch of parallel gated walkways. Nearing Central Park West, where the double formation slews off to continue its run downtown, it is joined by yet a third gated path. The effect is–deliberately, no doubt–disorienting. It is salutary, at times, not to know where you are or where you’re going. The experience takes you to places you would otherwise have missed.

Photo: Wolfgang Volz

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

Eighth Annual Japanese Contemporary Dance Showcase

The strongest works demonstrated an international outlook, incorporating much Western influence while retaining a stylization and emotional obliqueness characteristic of Asian art. Village Voice 1/25/05

De Facto Dance

In Beginnings, they pace, twist, run, tumble, crawl, and pose in photo-op freeze-frames, intermittently spoofing the pretensions that can attach themselves to the creation of a dance. Village Voice 1/14/05

Yanira Castro + Company

The curtains fly up—as at a peep show—to reveal a wraithlike figure clad only in panties and a gauzy robe that suggests flayed skin. Village Voice 1/11/05

Lionel Popkin & Andy Russ

A shared program by Andy Russ and Lionel Popkin offered excursions to the studio and the kitchen (with adjoining bedroom). Village Voice 1/11/05