New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / through February 27, 2005

Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain is the new ballet that’s making news in the New York City Ballet’s winter season. One of Wheeldon’s bare-bones works, it’s set to a pair of unrelated short pieces by Arvo Pärt, the Estonian composer given to spare constructions in grave moods who is so appealing to today’s choreographers. Three couples—Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto, Sofiane Sylve and Edwaard Liang, Maria Kowroski and Ask la Cour—dance to the first movement of Tabula Rasa; then Whelan and Soto dance as an isolated couple to Spiegel im Spiegel (Mirror in the Mirror). Wheeldon is returning to familiar ground here. His Liturgy also used music by Pärt, and, in the current edition of New York City Ballet News, he describes Whelan and Soto as his “favorite partnership.”

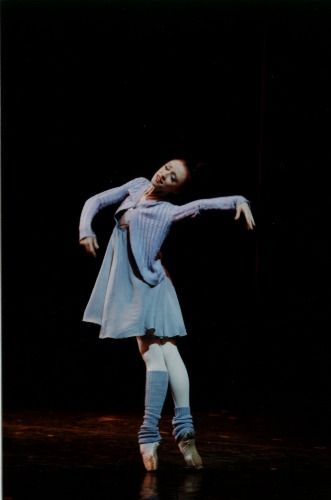

In Part I of After the Rain, the dancers wear gleaming skin-tight practice garb in subtle tones of blue and gray. The opening statement has the women facing the audience dead on as they plunge into arabesque penchée on pointe; the men partner them briefly from a supine position—a reference, perhaps, to the Agon pas de deux and the first duet in Violin Concerto. Throughout, Wheeldon emphasizes the sleekness, suppleness, and steely strength of the women’s bodies, with the men seeming to root them, playing the role of solid tree trunks to their willowy branches. All the moves, incised on the vast space, are so clean and clear they might be calligraphy; they make their impact as much by means of design as through action.

Here, as usual—in fact, more so than ever—Wheeldon displays an impressive mastery of choreographic craft. Every configuration is duly intelligent and handsome. His placement of the dancers in the stage space is sometimes inventive and invariably striking. He knows how to limit his vocabulary so as to lend greater force to the elements he’s selected. He makes already gorgeous dancers look like demigods fit for the glossies, thus appealing in a very contemporary way to the yearning in the spectator to identify with, aspire to, or perhaps to own—if only for a fleeting moment—something of what our current culture recognizes as beautiful. More than any other ballet choreographer working today, Wheeldon knows how much and when. What more could anyone want? Most observers, dance critics in the lead, are so grateful for what Wheeldon can do, they don’t ask for much more. Me, I find nothing moving behind the craft—no hint of the deep feeling that can permeate ostensibly abstract work, no creation of an architectural universe that proposes a mysterious and absorbing world in itself. I’m waiting, patiently and hopefully, to have my mind changed, but I keep remembering that, by all accounts, the genius of—to name some names—Balanchine, Ashton, Graham, Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp, and Mark Morris, was evident from their earliest works. In the case of the last three, I’ve witnessed the miracle with my own eyes.

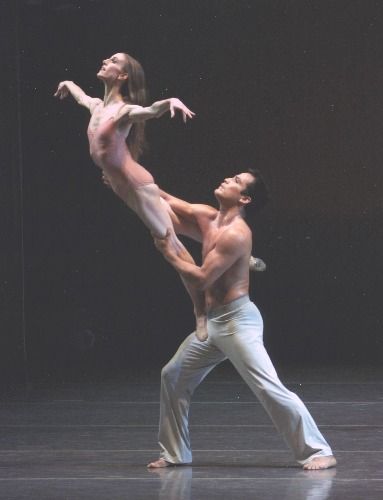

Part II of After the Rain takes us to a private—almost sealed—realm in which Whelan and Soto reveal themselves more intimately, a state of affairs first indicated by costume. Whelan is now all pale naked flesh, but for a rose-tinted leotard; her hair falls loose to her shoulders. Soto is bare-chested, in white trousers. Both dancers are barefoot—a condition that, though the norm in modern dance, packs a dramatic charge in classical ballet.

As everyone talking about After the Rain seemed aware, Soto is about to retire from performing, and this, apparently, is the last role he’ll create. The dancing indicates the woman’s sense of loss and hints, as well, at Soto’s grave devotion—to his partners, who have much to be grateful for, and to the stage. The two body types—Whelan’s attenuated as a Giacometti figure; Soto’s cousin to the squared-off solidity of the Aztec sculpture we’ve been seeing at the Guggenheim—intensify the contrast suggested earlier, the man’s rootedness allowing the woman to extend herself perilously into uncharted space.

All fragile grace carried to a near-grotesque extreme, Whelan repeatedly lets Soto float her into the air, where she seems as wispy as shreds of cloud wafting across a summer sky, then collapses softly, letting the energy ebb away from her infinitely pliable skeleton. (The piece forgets that Soto himself was once an airborne dancer—chunky, yes, but wonderfully buoyant. Wheeldon is too young to have seen this aspect of Soto live.) A viewer susceptible to the choreography and to the evocative duet for violin and piano accompanying it, may understand the earthbound Soto figure as enabling the Whelan figure to ascend to the realm of pure spirit. Or the woman as an emanation of the man’s own desire to detach himself from mundane reality as he aspires to the poetic. I must say I resisted these imaginings. Wheeldon hasn’t dealt much in his ballets with deep feeling, and his skirmishes with it here are, to my mind, only sentimental. I’m reminded of Jean Fritz’s comment: “I never cried over The Little Match Girl. I knew Hans Christian Andersen wanted me to cry but he wanted it too much.”

Photo: Paul Kolnik: Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto in Christopher Wheeldon’s After the Rain

© 2005 Tobi Tobias