Mandance Project / Joyce Theater, NYC / October 21 – November 7, 2004

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose, as the French say. The more things change, the more they remain the same. The proverb might have been generated to describe Eliot’s Feld’s choreographic career. Feld’s latest company, Mandance Project—consisting of five men and a lone woman—recently made its debut in New York with a repertory of 11 dances, all but one of them brand new. Astonishingly, the work looks like much that Feld, a huge but inexplicably stymied talent, has been doing for the last quarter-century. The pieces—six of them on the program I saw—are typically astutely crafted but rigid, confined, and obsessively repetitive. The very antithesis of early Feld works like Intermezzo and At Midnight, they say no to organic flow and depth of feeling, substituting aren’t-I-clever? gimmicks for the qualities that lie at the heart of expressive dancing.

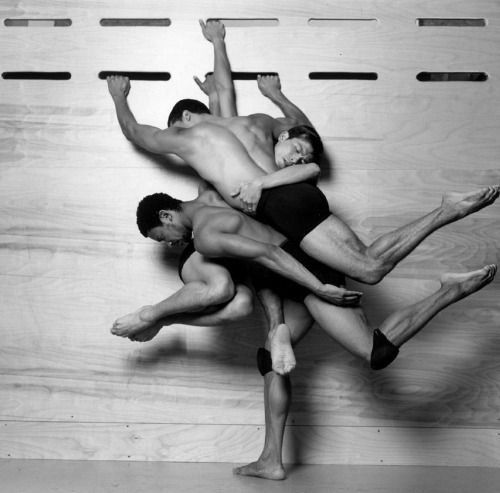

In Backchat, a trio of ballet boyz climbs up, down, and over a free-standing made-to-look-like-brick wall over and over again, performing the athletic feats of neighborhood thugs in picturesque formations. The wall is only  some 10 feet wide and stands in a vast field of empty stage space, but the three guys remain attached to their prop as if they were shackled to it. It’s not long before the viewer feels shackled too. Granted, Feld wants his audience to feel for these tough yet vulnerable guys; after all, he made his Broadway debut as a teenager in West Side Story. So he allots them a “dream” sequence in which they buddy up in slow motion (“Somewhere there’s a place for us”) and finishes by having them hang upside down from the top of their wall like victims of an atrocious crucifixion. Why, then, does he devote the bulk of his effort to making them look like a video commercial for athletic shoes?

some 10 feet wide and stands in a vast field of empty stage space, but the three guys remain attached to their prop as if they were shackled to it. It’s not long before the viewer feels shackled too. Granted, Feld wants his audience to feel for these tough yet vulnerable guys; after all, he made his Broadway debut as a teenager in West Side Story. So he allots them a “dream” sequence in which they buddy up in slow motion (“Somewhere there’s a place for us”) and finishes by having them hang upside down from the top of their wall like victims of an atrocious crucifixion. Why, then, does he devote the bulk of his effort to making them look like a video commercial for athletic shoes?

In Proverb, the young, sensuous, intensely concentrated Sean Suozzi is stripped to his flesh-tinted jock strap, a pair of Prodigal Son sandals, and lights that he cradles in his palms. These provide what seems to be the only illumination on the stage. At one point, he seems to hold the world’s last spark of fire in his hand; elsewhere the gigantic, blurry shadows he casts on the backdrop threaten to engulf him. Much like similar Feld undertakings, this hackneyed business goes on far too long after it has made whatever point it’s going to make.

Rumors has three men and a woman in s&m black webbing hanging from metal hooks upstage, like meat in a butcher shop window. We peer at them through a downstage row of gleaming jointed metal rods that seem to have some industrial—possibly lethal—purpose. When finally (and not a moment too soon), the figures free themselves and enter the clear available space centerstage, they thrash and droop like a quartet of tortured Petrouchkas, each rooted to his or her individual spot. The finale allows them a measure of locomotion—which they employ to crash noisily through the curtain of rods—but then re-condemns them to their hooks. The suggestion of human atrocities sits ill with the chic look of the dance. Admittedly, this incompatibility has been popular for some time. Did it come to the dance stage via fashion photography or is it merely a sign of these dismal times? Rumors gives you all the time in the world to ponder this question.

A Stair Dance, a tribute to Gregory Hines (and, surely, a couple of older legendary tappers), sets five dancers on five abutting five-step staircases and—guess what?—sends them up and down. Also, in the belated fullness of time, around. Jiving on the steps, the dancers might be notes on a musical staff. The accompanying music is by Steve Reich, a composer to whom Feld frequently turns, almost as if he were using Reich’s repetition, which usually results in a freeing ecstasy, as an excuse for his own iterative compulsions. These, however, are more likely to make viewers feel as if they’ve been sentenced to an indefinite term in a box that keeps (very, very slowly, mind you) getting smaller and more devoid of oxygen.

Yazoo, originally created for Mikhail Baryshnikov, is an endless series of shenanigans with a Western twang, beautifully performed by Wu-Kang Chen. Jawbone, beautifully performed by Damien Woetzel, is yet another one of those Feld experiments in how long you can keep a dancer interesting onstage without material that has any intrinsic interest. Feld, with his exaggerated estimate of that length, has, over the years, reduced far too many superb performing artists to choreography that’s the equivalent of reading aloud from the phone book.

The dancers chosen for the Mandance Project (note the company name’s reference to Baryshnikov’s White Oak Project, with its implication of impermanence) deserve richer material. Nickemil Concepcion, Jason Jordan, and the alluring Patricia Tuthill were the standouts of Feld’s now disbanded Ballet Tech (and trained from the start in its innovative school). They, along with the equally outstanding Chen, hold their own with Woetzel, a veteran New York City Ballet principal, and Suozzi, who has been with NYCB for four years without that company’s yet recognizing his true worth. Mandance makes them look like six dancers in search of a choreographer.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Photo © Bruce Weber 2004: Studio photograph, uncostumed, of Jason Jordan, Nickemil Concepcion, and Wu-Kang Chen in Eliot Feld’s

Backchat.