Works & Process at the Guggenheim: Balanchine Continued . . . at Ballet Arizona / Guggenheim Museum, NYC / November 14 and 15, 2004

The first program in a series of four exploring the ongoing life of George Balanchine’s legacy showcased Ib Andersen, one of the most glorious of the Danish male dancers who “defected” to the New York City Ballet to be part of that incomparable choreographer’s world, and nine dancers of Ballet Arizona, where he is now artistic director.

With the company’s permission, I watched early afternoon class the day of the first performance. On a chilly stage, on a floor that was sticky in some places, slippery in others (these flaws would be corrected by curtain time), without musical accompaniment, Andersen put his dancers through their paces. Despite these less than favorable circumstances, it was evident that he has been managing, very effectively, to transmit key principles of the Balanchine style. The dancers’ work was brisk and clean; its goal seemed to be execution that is eloquent in its very stripped-down efficiency. Refusing the decoration or sentimentality that can prettify the classical vocabulary but inevitably smudges it, this way of working lets the step speak for itself.

Once the dancers moved from the barre to the center of the space, they revealed, in addition to swiftness and clarity, a sculptural dimension as well as a welcome individuality of physical type and temperament. This last made me recall the New York City Ballet of the fifties, when the company, of necessity, harbored a more variegated range of dancers than it does today, with a limitless talent pool available to it.

Like Balanchine before him, Andersen is a man of few words in class. He doesn’t explicate and he doesn’t exhort. He sets the steps—in canny, challenging combinations—watches keen-eyed, and corrects sparingly, matter-of-factly, and unerringly. Under his aegis, I imagine, one could learn quite a lot.

Andersen’s own choreography, seen in the evening’s performance, is another matter. On a single viewing, I found it baffling. He presented solos and duets drawn from a lengthy work, Mosaik, each excerpt to music from a different composer, and segments of Elevations, to Handel. With few exceptions, this choreography is simply not dancey. For whatever reason, Andersen chooses not to do what the music is saying, even dictating. Despite the allurements of the score, his choreography remains aloof, disengaged. It has other agendas, it would seem, but at first glance they’re unfathomable.

Much of the choreography is adamantly spare, and its steps or small clusters of steps refuse to connect. One thing is done, then another. Then another. To what purpose? one keeps wondering. And why the pauses in the action that are like pockets of dead air? A few of the dances seem to be very brainy, comments on the music rather than an emanation from it, or reflections on a “concept.” The Mosaik solo to some upbeat Rossini, for instance, charmingly danced by Astrit Zejnati, might be a deconstruction of bravura work. Another solo from the same piece, to which Joseph Cavanaugh brought admirable gravity and weight, suggested the half-life of a god sculpted in stone. But ideas don’t dance with much alacrity; indeed, they’re inclined to stasis.

When it comes to theme, Andersen seems to be preoccupied with isolation, alienation, estrangement—that is, with people remaining distanced even when they are coupled, with action that thwarts the body’s natural impulse toward coordination and flow. The results include perverse lifts and entanglements and an atmosphere dismayingly devoid of vitality.

All of this seems to contradict the dancer he once was: musical; lyric; a quicksilver athlete; a creature of the air, buoyed, it always appeared, by an ecstatic vision; a performer who had located his rightful artistic home.

The program offered two Balanchine items: the sublime adagio from Divertimento No. 15, which is danced by five couples who appear in sequence, like poignant but fugitive images amplifying the transcendent beauty of Mozart’s music, and the duet from Slaughter on Tenth Avenue.

The Mozart ballet was beautifully done, the dancing profoundly musical and filled with delight. The women, in particular, aimed for the kind amplitude that once—but, alas, no longer—made NYCB audiences weep in response to the sight and sound, perfectly combined, of ineffable beauty. Their cavaliers provided careful, sympathetic support. Everyone, despite individual limitations of anatomy and talent (blessings so cruelly rationed by the gods), rose to the occasion with an elegance of bearing that spoke of classical dancing’s aristocratic roots and a purity of intent that has become all too rare. This is the sort of mass transformation that only excellent artistic direction—based on taste, vision, and endless labor in good faith—can bring into being. The dancers were Lisbet Companioni, Michael Cook, Nancy Crowley, Paola Hartley, Natalia Magnicaballi, Kendra Mitchell, Elye Olson, and Zejnati.

The rendering of the Slaughter duet was, to my mind, diminished by a dimension lacking in its dancers. Magnicaballi and Cook, both fine as far as they went, didn’t go far enough into the realm of raw—adult—sensuality. They seemed to be a pair of teenagers astonished to find they’ve fallen crazily in love, like the appealing adolescents in a Robbins ballet. This lightweight reading is not what Suzanne Farrell (in whose company Magnicaballi dances) used to give us.

In between the segments of dancing, Andersen was interviewed by Lourdes Lopez, a former principal dancer at the New York City Ballet who is now executive director of the Balanchine Foundation. She is a perfect ambassador for dance, combining a keen intelligence with a gracious manner. She elicited from Andersen, who used to be shuttered in interviews, thoughtful comments on his handling of the Balanchine legacy and a vivid picture—frank, warm, and tinged with Danish irony—of his position as artistic director of a small company operating far from the hubs of classical dancing.

Here are a few fragments of their conversation—as accurately as I could record them on the fly:

IA, commenting on an amateur film Lopez screened that showed him at his fleetest, rehearsing one of the Mozartiana variations choreographed for him, with Balanchine applauding him at the finish: He used what I could do then.

IA, on Balanchine: Dancing his ballets was an education of how to be in life.

IA, on staging Balanchine’s ballets: I teach the steps and I teach what I think his intent was. It’s what I think he intended, which is of course not [necessarily] what he intended. And, like everyone else who stages Balanchine’s ballets, I put something of myself into it—because what else can you do?

LL: What do you think Balanchine wanted to see [in dancing]?

IA: Expressive bodies.

IA, on his position with Ballet Arizona: Arizona is pioneering country. A lot of people there don’t know much about dancing. Some do, but a lot don’t. You give that audience what it wants, and then you give them something that challenges them. I’m lucky enough to have shaped my own environment there. (Half joking) I tell the board of directors what they should think.

LL: (Laughing) That’s the Balanchine legacy in a nutshell.

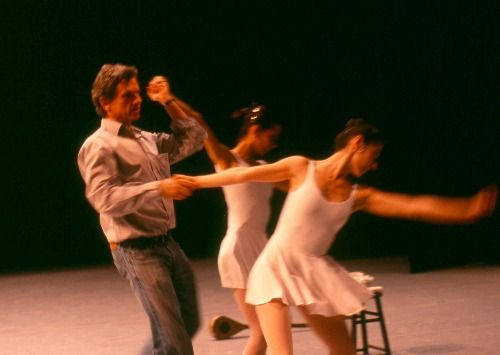

Photo: Harrison Hurwitz: Ib Andersen in rehearsal at Ballet Arizona

© 2004 Tobi Tobias