American Ballet Theatre / City Center, NYC / October 20 – November 7, 2004

Trey McIntyre—born in Kansas and trained at the North Carolina School of the Arts—is better known in the West than here on the East Coast, primarily for dances he created for the Houston Ballet and Oregon Ballet Theatre. But his grasp of composition, thought to be unusual in a young choreographer (he began at the age of 20 and is still under 35), has earned him freelance commissions farther afield—from the New York City Ballet (a decade back, for its Diamond Project) to Germany’s Stuttgart Ballet.

Pretty Good Year, set to excerpts from a Dvorák trio for piano, violin, and cello, lives up to McIntyre’s reputation for a certain competence. A plotless work for three male-female couples and an odd man out, who is its star, or at least its driving force, it deploys its personnel deftly and confidently. It segues with ease from a single duet to simultaneous ones, then evolves into a trio, a quintet, and so on, with the extra man silkily woven in and out of the proceedings. Superbly danced by Herman Cornejo, who has an innate feral quality, the figure might be the nature god Pan, igniting the erotic instincts of the eternally youthful shepherds and shepherdesses in his pastoral domain. (Liz Prince’s charming balletic-bucolic costumes support the idea.)

The ballet’s opening section creates a good-humored atmosphere, one full of genuine sweetness, with the dancers going through their paces like children at play, all bounce and verve. Even this early on, though, the busyness of the choreography—a step for every note, it would seem; lifts that are too coyly devised; an almost complete absence of stillness—threatens to exhaust the spectator.

The adagio section that follows, though cannily constructed, is also marred by McIntyre’s hyperactive impulse; by his continuing to favor the curvy, buoyant moves of allegro dancing rather than switching to the more appropriate reaching, languid lines that make for poetry; and by a strange, seemingly arbitrary motif of small writhing gestures. Here, set against a colloquy for a pair of lovers (Zhong-Jing Fang and Bo Busby), the work for Cornejo expands handsomely in scope and dynamics, so that he seems to charge the space with unquenchable energy—until, inexplicably, he falters, to be gathered up in the other young man’s arms as if he were a flagging child succored by a tender parent.

By the time the dance moves on to a predictable jovial male-competition duet, the viewer him- or herself will be done in simply by the plethora of steps and the accompanying lack of information about the nature of the participants and their agenda. McIntyre makes suggestions, but they’re not powerful enough, and they fail to cohere. Pretty Good Year ends with the return of the three couples, more animated than ever, with Cornejo rushing about among them, seemingly egging them on, then falling flat on his back, spent. As climaxes go, it’s been done before—and more tellingly.

Wheeldon’s VIII investigates the critical moment in British history when—for reasons of lust, love, and a pressing need for a male heir—King Henry VIII forsakes his queen, Katherine of Aragon, for Anne Boleyn. After some juggling with the religious law of the land (not shown), Anne becomes the second of the notorious monarch’s six wives. However, like the pious, plaintive Katherine, the keen-witted, provocative Anne is unable to produce the required princeling, and so it’s off with her head and on to her successor, Jane Seymour, a delectable little thing who catches Henry’s eye just before the curtain falls.

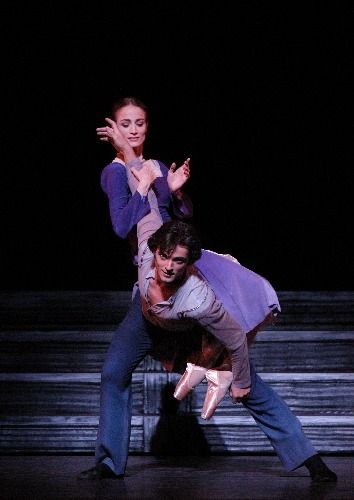

Wheeldon has chosen not to make this vivid raw material an occasion for dancing, but Alexandra Ferri, who is celebrating her twentieth year with ABT, manages, through some quiet, intense acting, to portray a Katherine who is a vessel of mystery and grief. By similar means, Julie Kent creates an Anne whose intelligence, independence, cunning, and erotic appeal are almost palpable. Both portrayals create a definite character, and both have immense dignity. As their sometime husband, Angel Corella is miscast. He’s not effective as a sheer kingly presence and has been given no choreography that would show the mettle he’s revealed in dozens of other, widely varied roles.

Wheeldon, abetted by his choice of score, Benjamin Brittens’s Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge, creates a somber mood that seems to repress dancing. The piece is governed by a formal severity that has the “ghosts” of Henry’s half-dozen wives haunting the premises. They are, indeed, striking. Rigged out in aristocratic Renaissance regalia (they don’t dance, so they can be laden with costume), they look like a gallery of Holbein portraits elongated to full-figure. But then the key duets, between Katherine and Henry as well as Anne and Henry, which should, logically, quicken the action of the piece and raise its emotional temperature, are hieratic and oddly unexpansive—even when the king first beds the seductive Boleyn—as if they were indicating situations and their accompanying emotions rather than enacting them. Wheeldon, who knows his craft, dutifully offsets this constriction and gravity with the rakish antics of a quartet of court entertainers, but then neglects to make the two modes of behavior inflect each other. The court—eight men and eight women strong—thrashes about busily and handsomely, but remains anonymous. Its members appear to have little relation to the principals and certainly no opinion about what’s going on, though you’d think their ranks would be rife with it. The only indication of the convoluted intrigues that must have been a part of Henry’s affairs is an ongoing motif of people watching each other from a distance in the ominous pervading gloom. Still, the act of watching, however potent a contribution it makes to the atmosphere of a dance, does nothing to enliven it in terms of motion.

As a whole, VIII has the air not of a dance or dance-drama but of a pageant. This is understandable given the fact that Wheeldon, though he has pursued his career in the States for the last decade (he is now Resident Choreographer with the New York City Ballet), comes to us from Britain, a land where the pageant genre has long flourished. Wheeldon’s origins also account for the fact that he may be rather more interested in Henry, Katherine, and Anne and their place in history than is your average American, despite his or her obsession with the misadventures of Prince Charles and Lady Di.

Next week I’ll report on ABT’s current renditions of two Fokine works, Les Sylphides and Le Spectre de la rose. Oldfangled though it may be of me, I’ve always had a penchant for yesteryear’s artifacts. In the case of dance, the most ephemeral of the arts, the survival of anything from the past in anything like its original form is little short of miraculous.

Photo credit: Marty Sohl: Julie Kent and Angel Corella in Christopher Wheeldon’s VIII.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias