Johannes Wieland / Diane von Furstenberg the Theatre, NYC / October 7-10, 2004

Johannes Wieland opened his recent concert with his 2002 Parietal Region, which, for the uninitiated, might serve neatly as Wieland 101. As this piece reveals, the choreographer, whose stern aesthetic may be related to the Bauhaus movement in his native Germany, favors austere architectural settings and groupings, along with a parallel emotional reticence.

Frederica Nascimento’s set for the piece features six austerely white boxes, two of which, with transparent “windows,” serve as cages—and, secondarily, jungle gyms—for a quintet of dancers (Julian Barnett, Brittany Beyer-Schubert, Nicholas Duran, Eliza Littrell, and Isadora Wolfe). In this bleak, handsome landscape, different but related activities occur simultaneously in various locations. Each of them is interesting on its own, while the stage picture as a whole is visually coherent, and, in that sense, meaningful. Here, as in his other works, Wieland proves himself to be more of a visual choreographer than a visceral one.

Needless to say, the set dehumanizes the dancers. The main box makes you think of a living-room aquarium, its confined denizens entirely at the mercy of random gazing eyes. When an inhabitant stands erect in the structure, the top of the frame cuts his head off from view. That overhead frame also conceals the equivalent of a chinning bar. Dancers inside the box hang from it at intervals. One woman swings from it upended, like a body taken from the gallows and hung to blow in the wind for passersby to notice, if they will.

The piece is handsome and ruthless—and part of its ferocity comes from the fact that both dancers and choreography do their best to seem affectless. But Wieland has another card up his sleeve. His dancers, who move with the sudden, lethal action of switchblades, are also extremely sensuous. Behind their lack of overt expression lies a potent universe of moods. Most of the feeling suggested is typical of our times—cool, subliminally hostile, and despairing. Nevertheless, it is there, working on the spectator’s emotions.

Parietal Region is clearly the ancestor of the new Corrosion, whose six dancers (the above, plus Branislav Henselmann) dwell in a recognizable contemporary world where love seems impossible. In changing-partners couples, they manipulate each others’ bodies, all the while apparently incapable of—perhaps immune to—effective communication. They seem more aware of invisible observers than they are of each other. An embrace is anatomized in slow motion; rites that should pass for intimate are performed eyeing the audience, as if gauging the anonymous public response. The prevailing climate is one of imminent disaster, though the piece never offers the catharsis of actual calamity. Just about every moment in it would make (does make) a still photo worthy of the high-end glossies.

Espen Sommer Eide provided the atmospheric electronic music for Corrosion, manipulating his equipment onstage. Diane von Furstenberg, who provided the theater for the concert—it’s part of her atelier, in the Manhattan’s fashionable Meatpacking District—designed the costumes. Much to her credit, the pearly gray outfits are suitably draped for the action of highly flexible, highly articulate bodies. The women’s dresses, translucent over their breasts, with skirts that cling to the hips, then flare out in clusters of pleats, make their wearers look like latter-day goddesses. The charm of both the men’s and the women’s outfits lies in the fact that they could be worn on the street in that downtown locale, where trendy restaurants and boutiques indicating fashion’s future spring up amid the persistent odor of dried blood.

The program included a newish trio, One, seemingly a three-ages-of-man affair. It’s full of Wieland trademarks, but vague in both its matter and meaning. Still, it was performed with distinction by two dance-world “elders”—the 65-year-old Gus Solomons jr, who, with one of the greatest mature faces in contemporary dance, brought to it a near-tragic dignity, and Keith Sabado, who, at 50, continues to be a paragon of delicate precision. Wieland himself—35, but an old soul—offered little more than physical fluidity coupled with a reservation so adamant, he seemed to be avoiding the audience’s scrutiny. I suppose this, in itself, is an artistic statement of sorts.

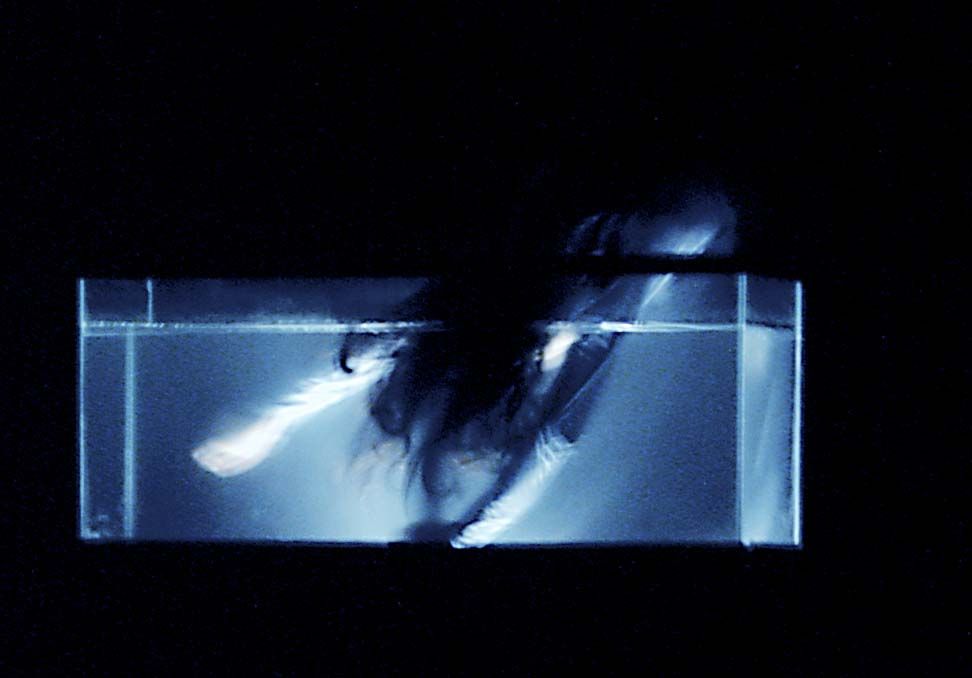

For me, the only dance on the program with more than visual or cerebral impact was the 2000 Tomorrow, named for and accompanied by the Richard Strauss song “Morgen!” (recorded by Jessye Norman) as well as passages of silence. Its “set” consists of three boxes, placed upstage, that are real aquariums. A trio of dancers (Barnett, Beyer-Schubert, and Littrell) lean over them to immerse their heads in the water for just a little longer than is comfortable to watch (and, no doubt, to do), then emerge from this near-death experience to splash the air and floor with giant droplets in wave-like arcs.

Though the dance then moves away from the tanks, it keeps returning to them. They are both objects and places, and they constitute the core of the piece. One of the women dips her brow and arm into the water in a singularly lovely gesture that might belong to a religious ritual. It suggests baptism, or a plea for—and gracious granting of—absolution. In a more violent (and typical) passage, the other woman (I think it is) holds the man’s head under water. This act—essentially inscrutable, as is much of what happens on Wieland’s stage—seems to lie somewhere between childish prank and erotically tinged cruelty. Later, the man, as if losing control, flings himself upon a tank and savagely strikes the surface of the water. The sound created by the impact is more terrifying than gunfire.

In between the encounters with the water there is much terrestrial thrashing about, much of it with the dancers sitting, lying, and rolling on the floor. More specific images of combat between an erect pair are witnessed by the third figure, whose arms and head hang limp, the very image of a person defeated by an environment that’s both hostile and hopeless and offers no viable alternatives.

The dancers wear silvery costumes by Stefanie Krimmel that might have been fashioned for postmodern garage attendants, and these designs are as integral to the piece as might be imagined.

I thought the whole business was fascinating and beautiful. It sold me, once again, on the idea that Wieland is a substantial talent. I wonder when—indeed, if—he’s going to unlock the box in which he’s confined himself among his personal obsessions.

Photo credit: Sebastian Lemm: Johannes Wieland’s Tomorrow

© 2004 Tobi Tobias