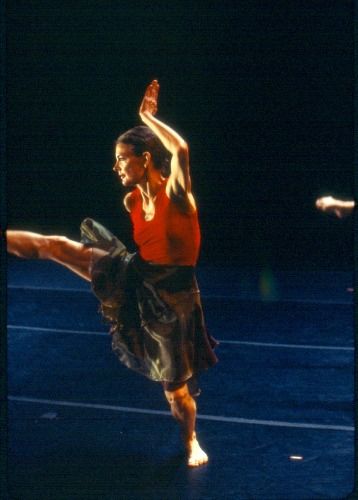

Molissa Fenley and Dancers / The Kitchen, NYC / September 29 – October 9, 2004

More than a quarter-century after Molissa Fenley first appeared on the postmodern dance scene, an oddity in her way of moving—apparent throughout the cycles of solos and group works she’s choreographed—remains a distinct personal signature. She holds her hands sharply angled at the wrist, palms very flat, fingers tight together, thumb joined to them or splayed outward. This articulation, at once awkward and graceful, is accompanied by an unusual fluidity in the arms and a sentient pitch to her torso. It gives her a feral air, which is augmented by her intent concentration. She has passed this creature-like stance on—as far as any individual way of moving can be replicated—to the five women, at least a generation her junior, who joined her to perform some of her new and recent choreography in the first of two programs at the Kitchen. (The second, to run October 6-9, constitutes a revival of her 1983 Hemispheres.)

The look I’ve described proved to be most effective in the atmospheric sextet Kuro Shio, created in 2003. Set to music by Bun-Ching Lam called Like Water, this dance does, indeed, suggest an imagined natural world. The creatures disporting themselves in Evan Ayotte’s soft silvery jeans and translucent shimmering tops under David Moodey’s low, azure-filtered light might well be postmodern neriads. And while they are happily diverse in ethnicity, coloring, and body type, the dancers (Ashley Brunning, Tessa Chandler, Wanjiru Kamuyu, Cassie Mey, and Pan Tanjuaquio) are all clearly disciples of Fenley, who works among them, serving as the model for their inner-directed focus; their poised, unemphatic reiteration of gestures and groupings; the hieroglyphic work of their hands and arms.

The new piece, Lava Field, to John Bischoff’s Piano 7hz, is not as successful. It delivers a familiar Fenley message about the certain, if essentially unfathomable, connection among living things. In a kind of prelude, three women gently fit their bodies together. Lying on the ground, they move with the fluidity of molten lava—pouring in streams and coalescing in rivulets—as if they represented an ocean born of fire now lapsing into quiescence. When they’re erect, forming abstract stage patterns that allow them to disperse only to re-bond as parts of a matrix, the same principle holds. The implication is that interdependence, observable throughout inanimate nature, is no less present in human relationships.

The problem is that this is not exactly news and, in Lava Field, Fenley gives it no particular illumination or even intensity of statement.

Throughout the piece, the movement is very arm-y and leggy, as is this choreographer’s wont. Here you begin to wish—at least I did—that she would allow the mid-section of the body to take charge more, serve as an energy center, initiating the impulse for the dance and provide a compelling urgency in place of a calm that is neither hypnotic nor ecstatic but, rather, flaccid and monotonous.

From the first, I think, Fenley’s choreography has suffered from a condition that plagues all of modern dance—the limitations of a vocabulary derived largely from a single body’s instincts. It’s instructive to study how and to what degree some of the greats in the field—Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Mark Morris—have escaped from the prison of self.

Photo credit: Paula Court: Molissa Fenley in her Lava Field.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias