Limón Dance Company / Joyce Theater, NYC / September 21 – October 3, 2004

The Limón Dance Company is unabashedly old-fashioned. Adhering to the principles of its founder, José Limón, and his mentor, Doris Humphrey, it acquires new works that match its existing repertory—well-made dances on humanistic themes, the prevailing modern dance mode until things fell apart some four decades ago.

Phantasy Quintet, by Adam Hougland, a former dancer with the group, is a perfect example of the genre. Set to the gentle, evocative Ralph Vaughan Williams score from which it takes its title, it gives us a small community from which a young man and woman emerge and experience love for the first time. All freshness and rapture, the couple embodies the awakening of spring in a pastoral world, and the people surrounding the pair rightly recognize in it aspects of the divine. Hougland restricts himself to a small, suitably selected vocabulary—mostly lyrical stuff with some dynamic reinforcement from Graham technique—and pays careful attention to structural coherence throughout. His work is the antidote to the “whatever” method of choreography that today passes for cutting edge. His dance may be a shade too tautly controlled and just a little tame, but it is radiant, and that’s what you remember best.

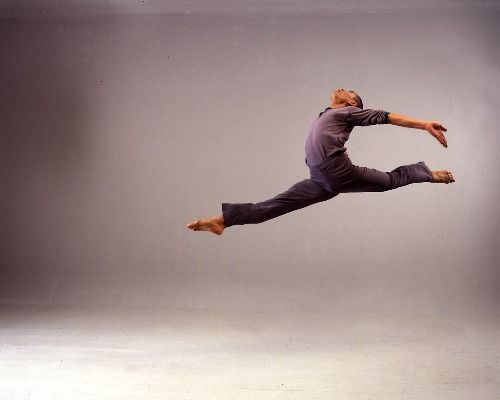

Hougland’s all’s-right-with-the-world piece was aptly set back to back with Limón’s Psalm, a model of scrupulously crafted form shaping content that thrums the heartstrings. Created in 1967 and now performed to a score commissioned in 2002 from Jon Magnussen, Psalm is a long, somber, visionary work for a large ensemble and a male soloist. A program note for the piece refers the viewer to the ancient Jewish idea that a few chosen men act as vessels for the world’s griefs, preventing them from overwhelming humankind at large. But the dance easily accommodates alternative readings. In fact, it might be the mirror of today’s troubled world, with its agitated phalanxes of people in search of leader, cause, and—simply—meaning; its agonizingly tortured victim, whose patient suffering and expiring is repeated again and again; its brief but piercing moments of succor and empathy; its portraits of endurance; and its impulse to ecstasy. I saw the affecting Robert Regala (who looks like a saint rather than a hero) in the leading role, with Kristen Foote and Roxane D’Orléans Juste as ministering angels.

A brand-new work by the German neo-Expressionist choreographer Susanne Linke, about which I wrote a short preview piece for the Village Voice, provided another latter-day echo of Limón’s concern with human predicaments. Extreme Beauty, a quintet for women set to music by György Kurtág and Salvatore Sciarrino, seems to deal with the physical and social restrictions imposed on women by prevailing dress codes. The costumes, by Marion Williams, are indeed handsome and inventive, but the dance itself hasn’t gelled yet. Some segments, like the opening wall of fierce women that recalls Graham’s Heretic, go on too long without making any specific point. Others appear to be after a kind of wit at odds with the situation as a whole. (Borrowing the Schiaparelli hat that’s an upended stiletto just strikes the wrong note when you’re adorning your virgin bride with a crown of thorns.) What’s more, the performances themselves are not fully focused, and thus lack both individuality and power. Linke is best known for her introspective, even hallucinatory, solos; her performances of them are unforgettable. But here, not even the superb D’Orléans Juste, who plays the central figure, achieves the subtle textures and the riveting intensity she regularly offers elsewhere.

Elsewhere in the repertory, admirable dancing prevailed. On occasion it escalated to the level of glorious. Among the women, D’Orléans Juste carries on the tradition of Nina Watt and the company’s artistic director, Carla Maxwell—both now serving the Limón legacy behind the scenes—of senior dancers who grow increasingly profound with experience. Jonathan Riedel and Kurt Douglas are, to my mind, currently the outstanding men.

Douglas, with his innocent baby face and a chest that seems to have been sculpted by assiduous hours at the gym, is, first of all, very beautiful to look at. (Yes, looks count in the performing arts; it can’t be helped.) And he’s a formidable technician. In Limón’s The Unsung his downward plunges are infinitely lush; his aspirations upward, soaring in spirit as well as body. His huge buoyant jump animates the celebratory final section of Lar Lubovitch’s Concerto Six Twenty-Two as if it were the choreography’s motor. But the most important thing about him may be that he makes you instantly happy. His joy at moving in space is contagious. He makes you feel, body and soul, his own avidity.

Riedel is surely one of the most fascinating dancers the company has harbored. Entrusted with Chaconne, the famous long solo Limón made for himself in 1942 to a section of Bach’s Partita #2 in D minor, he did an exquisitely tempered job, failing to make the observer believe fully in the undertaking simply “because he wasn’t José.” Limón, one intuits from his choreography and the memory of his performances, enjoyed the blessing of single-mindedness. The world was a clear place for him, with right and wrong well defined and easily articulated. His impassioned vision gave him the courage of his convictions and the ability to turn them into drama. Riedel, by contrast, is a child of his times. He has the haunted looks of a fallen angel and always seems to be torn—often tormented—by conflicting forces. He represents, magnificently, the contemporary predicament. While Limon favored magisterial gesture that commanded the stage space and declared it to be the entire universe, Riedel treats space as if it were dangerous and his position in it equivocal. His balancing act—with its hints of the wildness (madness, even) that may go with playing the hero—is invariably compelling.

Photo credit: Beatriz Schiller: Robert Regala in José Limón’s Psalm

© 2004 Tobi Tobias