The Frogs / Vivian Beaumont Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 22 – October 10, 2004

I can’t imagine why Susan Stroman—best known as the choreographer of Broadway shows, sometime provider of diversions for highbrow sites like New York City Ballet and the Martha Graham Dance Company—didn’t make dance a stronger element as director and choreographer of The Frogs. Surely her collaborators on this entertainment, Nathan Lane (libretto, lead role) and Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics), knew what she does best.

The show itself is a disheveled affair. A timeline may help explain how it emerged in its present form.

405 B.C. / Aristophanes (the ancient Greeks’ king of comedy) writes The Frogs, in which Dionysus, god of wine and drama, crosses the fateful River Styx into Hades. His errand is to bring back from the dead a playwright whose words might be powerful enough to elevate the state of the theater and the minds of the Athens citizenry, which neither thinks nor acts, despite its social and political problems. A pair of his culture’s key tragedians, Aeschylus and Euripides, vie for his attention through a duel in quotations.

1941 / Burt Shevelove stages his adaptation of the play, updating the plotline, with William Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw replacing the Great Greeks.

1974 / Shevelove resurrects his show, coopting Stephen Sondheim (with whom he’d partnered on A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum) to turn it into a musical. The production is staged in and around the Olympics-sized swimming pool at Yale, which also happens to have a renowned drama school. Some of the students who participate in the production are Meryl Streep, Sigourney Weaver, and Christopher Durang—who go on to be seriously famous. It might have been best to leave wet enough alone. But no . . .

2002 / Nathan (The Producers) Lane, who has had a hungry eye on the 1974 show for nearly a quarter-century, hosts and performs the leading role in an abbreviated concert version of it.

2004 / Lane re-revises the Shevelove libretto extensively. Sondheim is prevailed upon to write a half dozen additional songs. Susan Stroman, as indicated, is signed on to direct and choreograph. The current Frogs opens—to reviews that are mixed, to put it graciously—as part of this year’s Lincoln Center Festival.

A funny thing or two has happened to the original Frogs on its way to the present. It has grown increasingly politicized. The creatures who give the play its title have evolved from a simple chorus of amphibians that serenades Dionysus on his disquieting ferryboat ride into today’s know nothing, say nothing, do nothing populace, lulled by leaders of dubious qualifications to okay “a war we shouldn’t even be in.” The present version seems to fancy itself something of a left-leaning rabble-rouser, destined not to tour to the Red States.

At the same time, the latter-day Frogs has become more theatrically ingenuous. In the original, the Aeschylus-Euripides quotation contest is a parody; Aristophanes wrote all the lines. When the switch was made to Shakespeare-Shaw, the quotes were plucked (by a bunch of students) straight from the British playwrights’ texts. In the current version, the contest is reduced to a ludicrously unsophisticated argument between mind (represented by the witty, acerbic Shaw, who tells us what we should think) and heart (represented by the mellifluously humane Shakespeare, who knows how we feel). Guess who wins.

As for the ramshackle plot and the low jokes of the libretto in its present form, these admittedly have some roots in the original, but the tone of the whole affair has shifted to the point where I suspect Aristophanes himself—should he get a day pass out of Hades—might drop in at the Beaumont and declare “It’s Greek to me.”

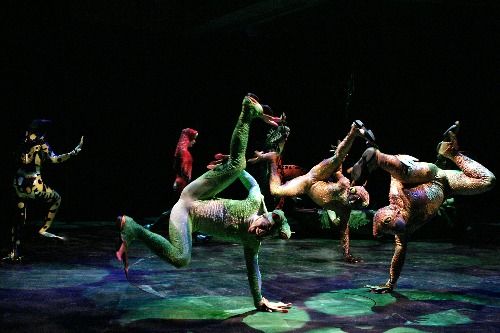

Now about this business of the dancing . . . Essentially, there isn’t any for what feels like the first quarter of the show, unless you count an octet in Greek tunics performing a sequence of stop-motion poses that parody the postures depicted with such grace on Grecian urns. Eventually Dionysus gets to the Styx and is traumatized—as we are amused—by the river’s population of frogs. These aquatic squatter-jumpers are played by dancers with formidable gymnastic prowess. Costumed in vivid body stockings and flippers inspired by dart poison frogs (a troupe of which is currently playing the American Museum of Natural History, they see no shame either in artificially enhancing their prowess via bungee cords or in condescending to a game of leapfrog. They dabble in ballet, too; if you haven’t seen a pair of amphibians doggedly churning out fouettés, now’s your chance.

In Act II, the Three Graces turn out to be a trio of pretty-as-hell, well-endowed, scantily clad aerialists contorting their pulchritudinous bods around long swaths of fabric that hang in loops from the flies. Once arrived in Hades, Dionysius and his trusty slave attend some revels thoroughly saturated with wine, women, song—and dancing that couldn’t be more trite. It’s as if the advancements in choreography for the Broadway musical made by Jerome Robbins had never occurred. In the same vein, a cluster of Shavian groupies does only routine vaudeville stuff. The regrettable paucity of dance in The Frogs is revealed most clearly in the show’s climax: The battle of the quotations is simply words, words, words, with the competing playwrights ringed by ten cast members who just sit and listen.

I have never taken much joy even in Stroman’s best choreography. The more frenetic its exuberance gets, the less I believe in the thrills it’s promoting. But I’ll concede that it has a verve that many find cheering—uplifting, even. And more of what I take to be Stroman’s equation of movement with the life force would certainly be welcome on this occasion.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Frogs in The Frogs.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias