Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

Oh, to be in England this year, the 100th anniversary of Frederick Ashton’s birth, to follow the many productions of the ballets with which the choreographer fashioned the shape and tone of British classical dancing! New York-based dance aficionados, at least, can console themselves to a certain extent with the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration—two weeks of repertory being offered by four companies: the Royal Ballet (Ashton’s own home base), the Birmingham Royal Ballet, the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago, and K- Ballet Company from Japan.

Ashton is, among other things (lyric poet, devotee of classicism, master of theatrical fantasy—and comedy besides, and consummate musician), the choreographer for people who revere the novels of E.M. Forster. Both artists specialize in delicate mood and the tender sentiment, continually embodying in their work what Forster, in his Howard’s End, termed “the voiceless language of sympathy.” “The affections are more reticent than the passions,’’ Forster wrote in the same passage, “and their expression more subtle.” Against all odds—ballets with literal content gravitate naturally to the more easily demonstrated subjects of ardent love and tragic death—Ashton’s 1968 Enigma Variations (My Friends Pictured Within) treats the idea of friendship so profoundly and poignantly, it might make even a misanthrope weep in empathy.

The ballet is set to the Edward Elgar score from which it takes its name, a suite of musical character studies of individuals in the composer’s circle. Ashton places the action in Worcester in 1898, the locale and time of the score’s composition, in the house and adjacent garden where Elgar is surrounded by his near and dear: his care-filled constant wife; a man who is his heart’s comrade; several endearingly eccentric friends (whose very absurdity invites affection); several ladies whose relationship to Elgar, though intentionally kept enigmatic, suggests the many faces of love (a flirtatious child-woman, a serene mature one offering a sensuousness that needn’t ignite, an ephemeral muse), and an assorted flurry of neighbors and functionaries.

The ballet is set to the Edward Elgar score from which it takes its name, a suite of musical character studies of individuals in the composer’s circle. Ashton places the action in Worcester in 1898, the locale and time of the score’s composition, in the house and adjacent garden where Elgar is surrounded by his near and dear: his care-filled constant wife; a man who is his heart’s comrade; several endearingly eccentric friends (whose very absurdity invites affection); several ladies whose relationship to Elgar, though intentionally kept enigmatic, suggests the many faces of love (a flirtatious child-woman, a serene mature one offering a sensuousness that needn’t ignite, an ephemeral muse), and an assorted flurry of neighbors and functionaries.

The Elgar we meet is often abstracted (an artist being essentially alone, no matter how dense and lively the population in his immediate vicinity). What’s more, he’s melancholy, at moments despairing; having arrived at early middle age, he has not yet achieved the recognition his talent deserves. The single “event” that occurs in the ballet is the delivery of a telegram announcing that the celebrated conductor Hans Richter has agreed to conduct the first performance of Enigma Variations—the score that was, finally, to make Elgar’s name. (Granted, some of this information relies on a program note, but it is gloriously carried through on the stage.)

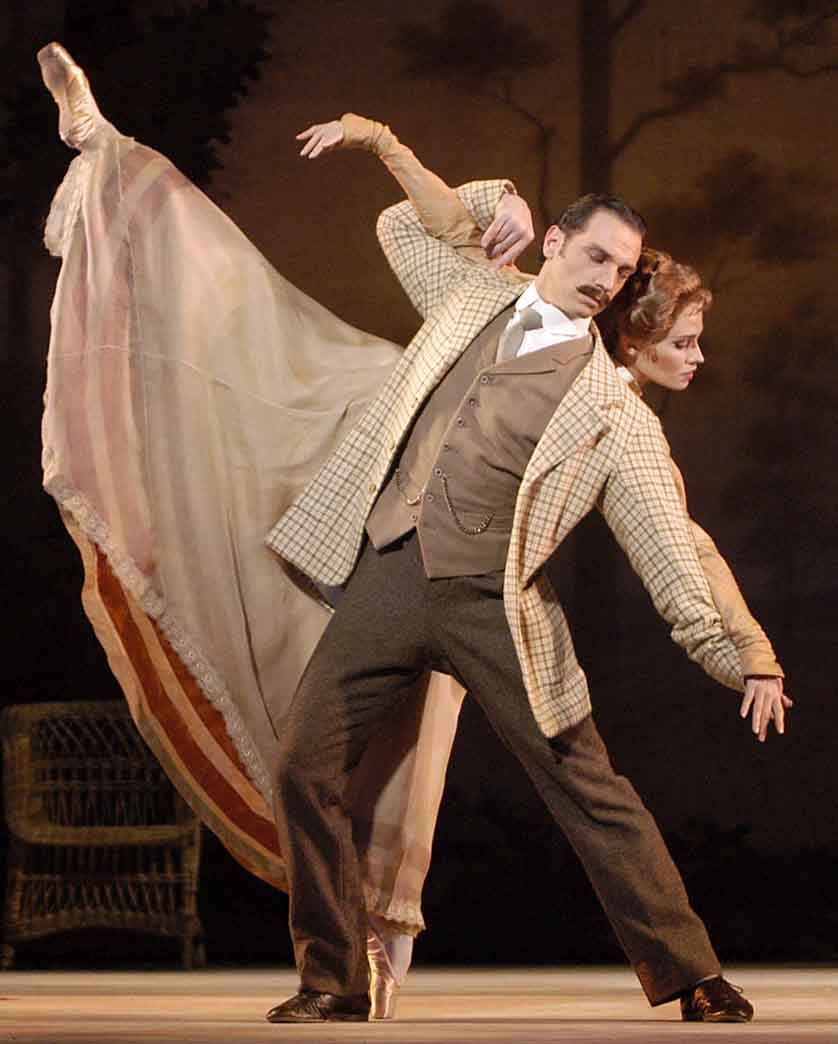

The ballet alternates between solo dances that set forth the temperament of the individual characters and duets, trios, and small groups that reveal the relationships among them. The amusing and the touching alternate in a scrupulous calibration typical of Ashton, while classical steps and naturalistic gesture are seamlessly wedded to create a unique form of theater, one investigated elsewhere only by Ashton’s contemporary Antony Tudor.

Two passages in the ballet quietly proceed to leave you shattered. One is a duet for Elgar and his devoted wife. She seems to be saying—no, not saying, she’s too discreet for that, just feeling—I wish I could be more to you. I wish I could be everything to you; you are my life’s work. I wish I could give you what you want. But of course she can’t, because what her husband wants is the desire of an artist—to have his efforts (that is, his deepest communication of who and what he is) reach the public they might move. Though the composer’s wife may serve as his support and comfort, it is not in her power to make that happen. It’s impossible to imagine this concept being choreographed until you see Ashton do it perfectly.

A second piercing segment, called the “Nimrod” variation (for the nickname of Elgar’s closest friend), begins as a meditative “conversational” duet for the two men and expands into a luminous trio that includes Elgar’s wife. All the movement—simple, deliberate, and serene—conveys the idea that the three are bonded by shared experiences and ideals, and that this bond enables them to face life’s difficulties and disappointments with equanimity and hope. The passage also provides a psychological frisson in juxtaposing a pair of presumably closed intimate alliances—a marriage and a same-sex best friendship—and proposing that the three participants involved can establish another, parallel, form of intimacy.

While these and similar portions of Enigma Variations are Chekhovian, the solos for the ballet’s oddballs (all of them, tellingly, men) are Dickensian, brilliantly calculated exaggerations of acutely observed traits. Embedded in them are challenges to the performer’s virtuoso capabilities, and this contributes greatly to their wit. In turn, these vivacious set pieces are counterbalanced by the overall elegiac quality of the ballet, typified by one character’s thoughtfully and sympathetically observing others, unseen. At the very opening of the piece, Elgar’s wife stands on the landing of a staircase in the house, looking down at her husband with loving concern. Later, when two young people in the still-ingenuous stage of love enjoy an extended duet, Elgar, screened by the mist at the back of the garden, gazes at them as if in a reverie. One can easily imagine him recalling an earlier time in his life when romance was fresh and promised to satisfy all his yearnings. Such is Ashton’s suggestive power.

Enigma Variations, danced by the Birmingham Royal Ballet (which had its origins as a “second” company to The Royal Ballet, and now rivals it in many ways), was far and away the finest production on the opening night of the Ashton Celebration. (More about the other entries as the week progresses.) The dancers of this company, which has been making a point of cherishing the Ashton repertory—not given its full due in the UK, just as the Balanchine repertory is not fully honored in the States—have the Ashton take on classical ballet technique in their bones and blood. The unerring placement, the exquisite contraposto of the torso and arms, the fleetness and precision of the footwork—all this ravishing technical stuff has been bred into them. They don’t have to work at or worry about it at the moment of performance, when they need to be concerned with other matters, such as imagination and expression. It is simply a given. And it’s one of the most gratifying givens I’ve come across in a very long time.

Enigma Variations will be performed only once more in the current engagement, on July 9, along with The Two Pigeons. Tonight, July 7, the BRB will dance Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan and Dante Sonata, which the company had the resourcefulness to retrieve from near-oblivion. On the 10th, it will offer Dante Sonata and The Two Pigeons. Tickets to the Ashton Celebration are available. While the best seats would ravage the budget of most dance fans, they’re still cheaper than a trip abroad, and there are some good views from the higher regions of the house. And then there’s always standing room, which has a true-lover-of-art cachet of its own.

Note: David Vaughan, in his indispensable book Frederick Ashton and His Ballets (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1977), points out the passage from Howard’s End.

Photo credit: Stephanie Berger/Lincoln Center Festival: Joseph Cipolla and Silvia Jimenez in Frederick Ashton’s Enigma Variations.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias