Latsky personifies that state every dancer aspires to–in which intent and execution are one. Village Voice 7/26/04

Archives for July 2004

GOING TO EXTREMES

Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Heisei Nakamura-Za / Damrosch Park, Lincoln Center, NYC / July 17-25, 2004

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

In one, a sympathetic woman volunteers to serve as caretaker to the princeling who is hiding out for reasons too convoluted to record here. An objection arises: What if this woman’s youth and beauty should tempt the young man to sexual imprudence? (In truth, the lady in question is not so much nubile as the picture of matronly elegance, her bulky figure clad in a black kimono elegantly offset by touches of sienna and red, her soft, plump fingers manipulating a matching lacquered parasol—but we theatergoers know how to suspend our disbelief.) With furrowed brow and a sorrowful twist to her mouth, the woman ponders the problem. Then, seizing a taper from the burning brazier at her side, she heroically it presses to her cheek. When she removes it, the smooth white flesh is marred with a bloody wound. (The audience knows this is just a make-up trick, but gasps in horror anyway, because the performer makes the moment thrill with reality.) Her hands, all delicate agitation at the wrists, flutter with tremors of pain as she holds a cloth to the crimson streak. Offered a hand mirror, she confronts her scarred image, and now her whole body pulses with shock. Her face twists in her first voiced response to the event as if the burn had not merely ruined the outer layer of skin but also reached deep into muscle. “The face her parents gave her,” she declares, is now scarred for life, and she wants the onstage witnesses to know how much that disfigurement means to her. So, after the self-mutilating action that’s sensational in its brutality and courage plus the exquisitely calibrated physical detail of its aftermath, we paying voyeurs get to savor the irony of her verbally requesting understanding from her fellow characters in the play when she has already secured our empathy through the emotional intensity of her actions. From this scene, too, comes the telling line, “There’s no sense in matters of the heart, and the unexpected can always happen.”

Another, more extended passage, works as the centerpiece of the play. Danshichi, the tale’s chief character, quick to use force as reason, confronts his father-in-law, Giheiji, a low-life whose corruption is symbolized by his wizened body, filthy ragged clothes, and truly deplorable teeth. No paragon of everyday honor himself, Danshichi uses a fake bribe to make Giheiji right the most urgent of his numerous wrongs. Once Giheiji realizes he’s been duped, he heaps a torrent of abuse (some of it frankly scatological) on his son-in-law, taunting Danshichi into attacking him physically, reminding him all the while that the punishment for killing a parent is death.

Slowly the scene slips from rough comedy to a moral and emotional seriousness that belongs to poetry. And in the course of this progression, the scene, which can be imagined to have started at sundown, slowly darkens into night. The traditional black-veiled stagehands of Japanese theater move in with translucent lanterns extended on long poles, following the swiftly moving protagonists to illuminate their bodies and faces.

The ensuing battle—a tour de force blending sword swipes, body-to-body grappling, and profound psychological conflict that prefigures Macbeth’s—is so protracted it becomes hallucinatory. Danshichi, who has on his side a brute physical advantage and the single available weapon, is reluctant to commit a murder he’s sure both the law and the heavens will curse. More and more blood flows. The combatants’ clothing is gradually stripped away, and their hair hangs wild. The illumination grows increasingly fugitive, sometimes reduced to a single beam held up to a single crazed face. Eventually it becomes so dim that the frenzied action takes on the insubstantial air of a dream, then plunges into “endless night.” In the obscurity, the skeletal old man falls into a pool of muddy water and rises from it a dripping brown specter—not yet dead but already a ghost. Now, finally, Danshichi summons the courage (or desperation) to put his victim down forever and poses, briefly floodlit, a victor himself in extremis, passing his sword through a lantern’s flame, hysterically sloshing himself with buckets of water, as if, with these rituals, he might repossess his soul.

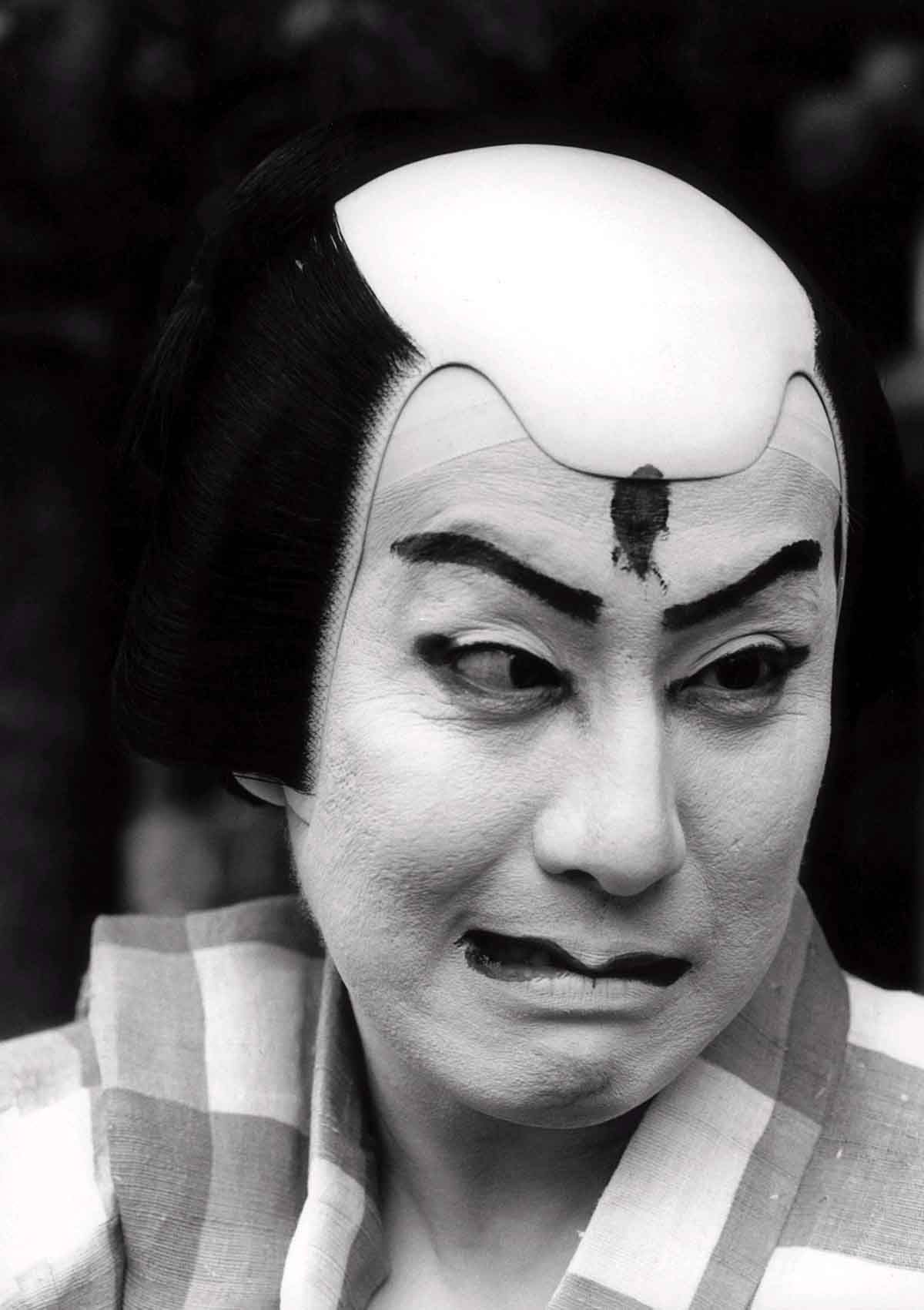

Have I neglected to mention that the self-sacrificing woman and the guilt-ridden warrior were played by the same actor? He’s Nakamura Kankuro V, a 48-year-old scion of a family that has been practicing the art of Kabuki since the 17th century. He does honor to his heritage.

Photo: Nakamura Kankuro V in Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka)

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

ASHTON CELEBRATION #6

Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

The Royal Ballet concluded the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration—an event that demands an encore—by offering irresistible entertainment: three performances of the choreographer’s 1948 Cinderella, set to Prokofiev’s evocative score. The first of them, featuring Alina Cojocaru in the title role, was one of the most intense (and innocent) experiences I’ve had in a lifetime of ballet-going. This ballet is like a perfect children’s book: simple in its means; fluid in imagination; rich in delights that appeal to the eye and echo in the heart; charged with incontrovertible morality.

Yes, morality. Consider this: Cinderella’s saga, so gratifying at the personal level—virtue, much put upon, finally reaping its just rewards of ravishing costume, sleek vehicle, and loving prince—has a larger dimension. It illustrates the triumph of order over chaos. The ballet opens with a scene of domestic discord—the physical and emotional cacophony engendered by the chronic ill will of the Ugly Sisters. The stepsisters’ physical homeliness, which verges on the grotesque, reflects the impulses—envy, vanity, and greed, among other of the Seven Deadlies—that dominate their lives and spoil the daily existence of everyone under their roof, from family down to servants and tradespeople. While the Ugly Sisters create clamor, Cinderella and her father represent harmony and peace. The ballet ends—not with a grand thousand-watt pas de deux, but on a gentle preview of the perfect accord that will prevail in the household of Cinderella and her prince.

And consider this: Cinderella is not merely a nice, goodhearted girl—the sort of person parents used to wish their daughters to become or their sons to marry. No, she is the very emblem of love. She’s charitable—literally to the Beggar Woman, spiritually to the stepsisters, whose hostility she meets with sweet-tempered tolerance and, in matters small and large, forgiveness. Even when she comes into her kingdom, she doesn’t banish those who had earlier relegated her to rags and ashes. (Ashton quietly records at least one of her tormenters’ recognizing this generosity and the luminous soul that extends it—and being just a little transformed).

From the first, Ashton’s Cinderella is seen to be greatly deserving. The Fairy Godmother, in working her magic to bring this unassuming heroine to her rightful destiny, puts the forces of nature at her service. Presenting her retinue to the girl, she seems to say, Here are the seasons. All of the earthly landscape is yours—gardens, forests. And here are the heavens—sun, moon, stars. Here are the hours. Time itself will bow to you, if you obey just one rule. (And Cinderella comes close to breaking that rule only because perfect love—something she knew only once before, from her long-dead mother—has, understandably, distracted her to the point of forgetfulness.)

The idea of terrestrial and celestial forces being summoned to transform Cinderella’s condition is much abetted by Toer van Schayk’s new scenery for the ballet. The appropriately inhospitable parlor of the home in which Cinderella is confined slips away upon the arrival of the Fairy Godmother, to be replaced with a backdrop suggesting the Milky Way. The stage is then transformed into an 18th-century garden for the presentation of Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter, each in her seasonally appropriate grotto, each with a girl-and-boy pair of child attendants who are as motionless and charming as porcelain pastoral figurines. When the Fairy Godmother, echoed by the dozen spirits representing the hours, instructs Cinderella on her curfew, a glowing golden clock, hands pointing to a fateful midnight, is suspended in the night sky, changing its guise on and off to that of a full moon. Once Cinderella is gowned and coached, a star-sprinkled forest gapes wide to reveal an imposing castle in the distance and heavens given over to meteorological fantasy. The ballroom is dishearteningly heavy, but it opens onto a formal garden offering the consolations of fresh air and exquisite proportion. Once, back in the gloom of her childhood home, Cinderella has demonstrated that the shoe fits, an apotheosis shifts the scene again to the bosom of nature, where the hours—now benign rather than warning—have acquired magic wands like the Fairy Godmother’s: star-tipped. The ballet’s final tableau echoes the idea of celestial collaboration; just as the curtain starts to fall, the heavens bless Cinderella and her destined love with a shower of golden stars.

The moral dimension of Cinderella’s character carries straight through to the ballet’s conclusion. Accommodating to the fact that Prokofiev’s score failed to provide for the sort of triumphant pas de deux with which program-length storybook ballets customarily conclude, Ashton excuses his modest heroine from lording her triumph over her foes, even from exulting in it among friendly inferiors. Instead, he assigns her a small duet with her prince in which she simply grows more gentle, more dulcet, and more luminous.

As I’ve said, the performance of this wonderful ballet that was led by Alina Cojocaru had an unforgettable radiance. Her small, delicate build helps her look suitably waif-like as the mistreated Cinderella, but this readymade pathos is quickly counteracted by the sweetness and spunk she gives to the character and by the gorgeous amplitude of her dancing. With experience she will learn to blend the two moods, the pathos and the sanguine resilience, as Margot Fonteyn did so memorably. Meanwhile, one appreciates the fact that Cojocaru’s spirited quality is not a matter of acting; it’s embedded in the speed, precision, and ebullience of her dancing.

In this very young ballerina, sheer beauty of physical proportion and technical perfection are matched. Examples of the latter: the ability to transform a striking still posture into dancing without smudging the imprint of the original shape; the ability to make a stream of minute, evenly measured turning steps precise and liquid at the same time. That sort of thing. Add to these gifts innate grace and musicality and you have something seen perhaps just once in a generation—something, by the way, evident not merely to the aficionados in the audience but to every last person in the house.

I still haven’t mentioned the modesty and sincerity of Cojocaru’s self-presentation (so apt for the role of Cinderella, so welcome on other occasions) or her evident joy in what she’s doing. My praise might be more credible if I could temper it with some minor complaint, but, truth to tell, there isn’t anything about Cojocaru’s dancing that I don’t like.

Johan Kobborg, Cojocaru’s frequent partner, makes a fine prince for her Cinderella. His demeanor may be more friendly than aristocratic, but he’s so unaffectedly agreeable, so infallibly caring, you feel the heroine’s future happiness with him is guaranteed. Like many another Danish-bred dancer, Kobborg maintains an attentive, responsive relationship to his fellow performers that seems entirely genuine. He’s wonderful, for instance, when Cinderella disappears for a moment and he asks the various couples at the ball where she might be, revealing how bereft he feels when nobody knows. Even before midnight strikes and he’s left with nothing of her but a single small, glittering shoe, you see that she has not simply aroused his devotion, but become his entire world. Still, Kobborg is not a danseur noble in looks or manner. Neither is he a topflight virtuoso. So I wonder sometimes—all the while grateful to him for both his engaging dancing and his sympathetic partnering—if he may not be playing Michael Somes to Cojocaru’s Margot Fonteyn. If so, I hope Cojocaru’s Rudolf Nureyev shows up well before she’s past her prime.

The roles of the Ugly Sisters originated by the darkly dramatic Robert  Helpmann and Ashton himself were danced, respectively, by Anthony Dowell (the great Apollonian danseur of his generation, who then directed the company) and Wayne Sleep (a diminutive, ebullient artist who has not forgotten he was once a high-flying virtuoso). The present incumbents are perhaps a shade too outlandish, and of course the audience encourages them. Ashton himself achieved a nuanced portrayal–part Dickensian, part Chekovian–that was as touching as it was amusing.

Helpmann and Ashton himself were danced, respectively, by Anthony Dowell (the great Apollonian danseur of his generation, who then directed the company) and Wayne Sleep (a diminutive, ebullient artist who has not forgotten he was once a high-flying virtuoso). The present incumbents are perhaps a shade too outlandish, and of course the audience encourages them. Ashton himself achieved a nuanced portrayal–part Dickensian, part Chekovian–that was as touching as it was amusing.

In descending hierarchic order, the Fairy Godmother, the four women representing the seasons, and the twelve representing the hours all embodied the Ashtonian aesthetic, from the contrapposto use of their torso and arms to the precision and delicacy of their footwork. Ashton’s choreography has many lessons to teach its dancers, and some splendidly compliant pupils were on view.

Photo credits: Dee Conway: In the Royal Ballet’s production of Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella: (1) Alina Cojocaru in the title role; Anthony Dowell (l) and Wayne Sleep as the Ugly Sisters.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

“Martha @ Jane Street”

In dance genius and diva chutzpah, Graham was indeed a phenomenon ripe for travesty. Village Voice 7/20/04

McCaleb Dance

McCaleb is intensely and admirably image-conscious, but more often than not, her pictorial effects fail to provide a pathway to eloquent feeling. Village Voice 7/20/04

ASHTON CELEBRATION #5

Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

The centerpiece of the Royal Ballet’s mixed repertory program for the Ashton Celebration was a quartet of pas de deux presented back to back on a bare stage. The content varied just a little from one evening to the next and the casting varied a lot, so that a goodly number of the company’s principals had an opportunity to win New York’s hearts and minds.

Programming clusters of brief dances—pièces d’occasion that have survived their original occasion and excerpts plucked from more ample contexts—is a time-honored way of attracting the general public to the ballet and pleasing fans who are more fascinated by star performers than they are by choreography. I succumbed myself, decades ago, to the Bolshoi Ballet’s “Highlights” programs (did they really play the old Madison Square Garden or am I making this up?). What I know for sure is that it was in that downscale context that, as an adolescent ripe for indelible impressions, I saw Galina Ulanova dance the Fokine chestnut known as The Dying Swan and became a devotee for life of what her simple soul-driven performance represented. The theory behind such tapas programming is that the responsibility of appealing to a spectator is better distributed among a variety of dances in a given time slot than riskily confined to a single one. Today, American Ballet Theatre peddles its mixed-repertory programs with a similar tactic.

Once I had seen a lot of ballet, I came to prefer, vastly, more substantial dances and material preserved within its original context. Still, the Royal’s “Divertissements,” as the company called the one-duet-after-another segment it sandwiched between Scènes de Ballet and Marguerite and Armand offered welcome delights as well as revelations about the dancers it showcased and the company’s overall choices about the manner in which it dances.

The pas de deux that Ashton added to the Awakening scene in the Royal’s production of The Sleeping Beauty is, as people complained at the time (1968), stylistically at odds with the Petipa’s choreography for that ballet. However, its delicate poetry in depicting Aurora’s emotions is entirely compatible with what, reading Perrault’s La Belle au bois dormant, we imagine to be the trajectory of Aurora’s feelings in the several tumultuous minutes that follow the prince’s restorative kiss. The tale implies that the princess has dreamed of the prince during her century of sleep. Ashton’s duet seems to trace her recognition of and gradual commitment to the man of her dreams once he has appeared in the flesh. Her love, at first tentative in its tenderness, steadily expands in confidence until, with a swelling heart, she seems to cede her kingdom and soul to a prince who, being (as Perrault assures us) a gentleman of matching sensibility, will respond in kind.

For his score, Ashton chose an extended violin solo that Tchaikovsky composed as entr’acte music for the ballet but which was dropped from the original production. Balanchine later borrowed it for the passage in his Nutcracker that serves as a prelude to the young Mary’s awakening to the terrifying and ecstatic universe created by Drosselmeier’s magic. It’s interesting, isn’t it, that both heroines—the just-nubile Aurora, and the pre-adolescent Mary—are, at the moment they dance to this music, connected to the state of a dream-haunted slumber.

Darcy Bussell’s incarnation of the Ashtonian Aurora pretty much summed up for all time the state of being ready to love and be loved. It sweetness and freshness were genuine as only a mature ballerina can make those springtime qualities, its radiance almost more than the eye and heart could bear.

Bussell was captivating once again in the pas de deux that climaxed the 1956 Birthday Offering, one of several Ashton pièces d’occasion that have, with good reason, earned a place in the permanent repertory. This one was devised to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the troupe founded and directed by the indomitable Ninette de Valois that was about to be granted, by court fiat, the title of The Royal Ballet. It showcased the company’s seven ballerinas, appropriately attended by male cavaliers. For each lady, Ashton fashioned a Petipa-style solo that reflected her dancing persona, relegating the men, whose prowess did not yet equal that of their partners (how times have changed!), to a communal mazurka. The pas de deux crowning these events was danced by the reigning stars Margot Fonteyn and Michael Somes. This duet eschews spectacular lifts, Ashton having been turned off such doings by the Bolshoi Ballet’s circusy tours de force, among other taste-deprived shenanigans then on the Rialto. It is compelling, however, in its unusual and challenging balances, which Ashton, being Ashton, makes look like dancing, not weird exploits. Ravishing in the ornate knee-length bell-shaped tutu designed by André Levasseur, Bussell approached the technical demands of her role as if they promised to be fun and subordinated them to a display of warm rapport with her partner, Thiago Soares.

Voices of Spring, too, began life as pièce d’occasion—being a surprise addition to a New Year’s Eve performance of Strauss’s Die Fledermaus in 1977—but, in this case, it’s a bagatelle that’s probably expendable. Its worth lies in its illustrating the fact that the trivia of genius may outshine lesser artists’ finest efforts. It takes off from bravura Soviet showpieces like Spring Waters, using some of the genre’s gasp-producing pyrotechnical devices, at the same time—and charmingly—inviting the viewer to recognize their absurdity. Two of the three teams I saw—Alina Cojocaru and Johan Kobborg, Leanne Benjamin with Inaki Urlezaga—did it proud. Cojocaru is simply the best thing to happen to classical dancing, ladies’ division, in a very long time, and her performances with Kobborg invariably demonstrate the pair’s potent onstage chemistry. Benjamin, however, provided the most perceptive and witty rendering, as if she had somehow intuited Ashton’s intentions.

The 1971 Thaïs, set to the “Méditation religieuse” music from Massenet’s opera, qualifies as a fully worthy miniature. Co-opting a favorite ballet theme, that of the poet-lover visited by his evanescent muse, it lends it a double twist: an oriental accent and an overt—if understated—erotic dimension. This alluring mystery-laden excursion is filled with beautifully appropriate lifts in which the woman’s body is sinuously wrapped around the man’s or cantilevered from it. Its pictorial high point, though, is the work with the veil under which the woman first appears to—and then leaves—the yearning man whose imagination she animates. Drifting under its swirling apricot-tinted folds in a stream of minuscule steps on pointe, she looks like a sunset cloud. I saw the two casts for this piece (Leanne Benjamin and Thiago Soares, Mara Galeazzi and David Makhateli), both of which achieved the clarity and grace the choreography requires, neither of which fully suggested the dance’s exotic perfume.

The only dud among the “Divertissements” duets was the pas de deux from the 1958 Ondine that culminates in the water nymph’s giving her mortal lover the kiss that means his death. This excerpt wasn’t even persuasive evidence of Ashton’s stated desire to create movement that captured the fluidity of water, “the surge and swell of waves.” Tamara Rojo worked hard to evoke the willful, untamed aspect of the title role, but you could see her working, so while the effect was praiseworthy, it wasn’t believable. Perhaps only Margot Fonteyn, on whom and for whom the ballet was created, could make this material convincing.

Overall—and I’ve now seen the “Divertissements” on three evenings running—the impression I have of today’s Royal Ballet is that of a company that places its highest value on technical precision in the legs and feet, a prescribed sculptural eloquence in the port de bras, and gentleness and gentility even in the execution of bravura feats and the rendering of powerful emotions. Other factors that one might look for in dancing—spontaneity, risk-taking, the projection of an individual stage temperament—are muted by some sort of consensus decision about dancing that the company has arrived at (no doubt, in part unconsciously). As happens anywhere under these circumstances, only the great stars—the Darcy Bussells, the Alina Cojocarus—transcend the prevailing code of behavior. What I wonder about the Royal is how many potential stars (I saw several, especially among the men) are being stifled by it.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

ASHTON CELEBRATION #4

Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

Q: What do Anna Pavlova, Isadora Duncan, Marius Petipa, and Euclid have in common? A: Serving Frederick Ashton as his muse. True, the geometrician of ancient Greece was not as frequent an inspiration to the man who essentially invented English ballet style as were the dance icons in this group. Nevertheless, he reigned over the abstract Scènes de ballet, choreographed in 1947, with which the Royal Ballet has just opened its week-long run at the Metropolitan Opera House. “I, who at school could never get on with algebra or geometry, suddenly got fascinated with geometrical figures,” Ashton is quoted as saying in David Vaughan’s Frederick Ashton and His Ballets, “and I used a lot of theorems as ground patterns for Scènes de ballet. . . . I also wanted to do a ballet that could be seen from any angle—anywhere could be front, so to speak. So I did these geometric figures that are not always facing front—if you saw Scènes de ballet from the wings you’d get a very different, but equally good picture.”

Apparently, what delighted Ashton in pure, rigorous mathematics was the similarity of this discipline to classical ballet, the principles of which constitute a codified system built to yield dancing that is harmoniously proportioned, exquisitely balanced, and grounded in logic both visual and anatomical. And Scènes de ballet, in its abstract and exquisitely inventive embodiment of the danse d’école, does recall Edna St. Vincent Millay’s famous proposal that “Euclid alone has looked on beauty bare.”

Structure is all-important to Scènes de ballet, being not simply an element of its composition but quite possibly its main subject. And this structure—the action organized for a ballerina, a male principal, four male soloists, and a female ensemble of twelve—is impeccable. Nevertheless, while everything in the ballet seems inevitable, almost nothing about it is ordinary. Every one of the dance’s 17 minutes contains several surprises: kaleidoscopic configurations, unexpected choices about who accompanies whom, stage patterns that seem to be evanescent landscapes in an imaginary world. The architectural design of the piece is so sound and yet so filled with wonders, you wouldn’t want a single element of the choreography to be otherwise. What you want, after the ballet has amazed you for the first time, is to see it again, immediately.

It’s well-nigh impossible to describe the happenings in an abstract ballet persuasively; the result invariably reads like a grocery list, while a choice among them often seems arbitrary. So I’ll content myself here with noting two aspects of Scènes de ballet that struck me especially. First, in the area of hierarchy (essential to ballet, which emerged from the royal courts), Ashton delivers, simultaneously, both an homage to traditional order and an ongoing proposal that all such givens can be rewardingly inflected. If, for example, classical dancing usually recognizes the ballerina as the queen of the proceedings, Ashton is not about to argue with such a useful tenet and gives the lady her due; however, it’s the commanding male principal who opens the show, surrounded by four male acolytes who represent the coupling of strength and grace. Second, since a Euclidean ballet seems to call for an adherence to Petipa, who prepared some of his choreography by manipulating chessmen in their grid-like field, Ashton responds with many of the geometrically inclined tactics Balanchine, also a Petipa devotee, would employ in the circumstances. Yet he always softens and colors his efforts with a Romantic-style fluidity that evokes the Fokine of Les Sylphides and the performances of Pavlova and Duncan.

Scènes de ballet is set to Stravinsky’s score of the same name, composed in 1944 for a more frivolous occasion, a Billy Rose revue called The Seven Lively Arts, where Anton Dolin choreographed the dance number for himself and Alicia Markova. The music allows for concerns lower-browed than Euclid’s, and Ashton indulges himself accordingly. His ballet provides intriguing psychological mystery—concerning the complex, ever-shifting relationships among the ballerina, her cavalier, the male soloists, and the female ensemble. It also—in its costumes and many of its gestures and poses—creates an aura of chic that suffuses the stage space in the way a perfume, with its invisible power, affects the atmosphere of a room.

The choreographer Kenneth MacMillan, who succeeded Ashton as director of the Royal Ballet, experimented elsewhere with the notion, shared by many, that the ballet’s original costumes and sets distracted attention from its classical virtues, that it would be better off shorn of this decoration. Granted, André Beaurepaire’s set looks like a trio of heavy architectural elements the stagehands forgot to haul away after an earlier opera performance, while the costumes will not be to everyone’s taste, being deliciously chichi (the women of the ensemble , for example, wear black pillbox hats adorned with insouciant white feathers). I happen to love the costumes, which now have vintage appeal added to their allure, and I believe the production as it stands is all of a piece and shouldn’t be meddled with. Its combination of transient delights and eternal verities seems to me typical of Ashton’s unique turn of mind.

It would be useful to note here that, in a comparison with many a Balanchine ballet set to Stravinsky’s music, Scènes de ballet emerges with honor. The Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration has reintroduced the British choreographer to the American audience for dance, an audience for whom Balanchine has long reigned supreme. This renewed interest in Ashton may spark a fruitful exploration of what the 20th century’s two foremost geniuses of classical dance choreography have in common—and what makes each distinctive. One hopes, too, that it will inspire more first-class Ashton productions from our native companies (ABT, this means you!) and more visits from the two Royals. For the last twenty-five years, the dance audience has been complaining about the dearth of new classical choreographers. All the more reason, during these relatively barren times, to cultivate the old ones.

Accompanying Scènes de ballet on the Royal’s mixed-repertory program—along with a cluster of pas de deux that I’ll discuss in my next posting—was Ashton’s 1963 Marguerite and Armand, now used as a vehicle for the company’s ranking guest artist, Sylvie Guillem. After seeing this star turn three years ago, I wrote: “Frederick Ashton created this hallucinatory sketch of Dumas’s Romantic melodrama La Dame aux Camélias in 1963 as a vehicle for Margot Fonteyn, whose technical powers, by that time, were at the vanishing point, though she remained a sublime creature of the stage. Guillem took it into her head to treat the ballet as if it had serious substance, working up a character that appeared to be rooted in the close study of novels by the Brontë sisters. This curious, even perverse, undertaking had a certain intellectual appeal—one, however, that had little to do with dancing. Fonteyn, with her innate ballerina instincts, had been content to play herself.” (New York Magazine, August 6, 2001)

Guillem’s current rendition of the role has, strangely, grown even less affecting. It’s so cool and small-scaled, it often seems blank. The ideas that fueled it are still there, but rendered so minutely, it’s hard to see how they could reach spectators in the upper regions of a vast opera house. Even in the privileged close-to seats, opera glasses were required to capture the fine details. And, wrongly, Guillem’s interpretation is stronger in the portrayal of mortal illness—the observations of a body wracked by T.B. might serve as a teaching aid for medical students—than it is in conveying the notion of undying love. I found myself wondering if, to get an appropriately fervid performance, we’ll have to wait until the Royal’s impassioned young Alina Cojocaru is old enough to need the role.

Though I’d vowed not to see this piece a second time in a single week, I’ve succumbed, after all, to the temptation of another look at Anthony Dowell’s interpretation of Armand’s father. The character is repressed and repressive, yet capable in the end of profound empathy. Dowell, former artistic director of the Royal Ballet and one of the supreme danseurs nobles of his generation, packs every restricted gesture with feeling, making it an Ashton cameo worthy of Enigma Variations (and related to Eric Porter’s playing of Soames in the original television version of The Forsyte Saga). Dowell will be onstage again in this role tonight and tomorrow, July 15. On July 16, he will portray one of the Ugly Sisters in Cinderella; on my list this event is a Don’t Miss.

Today is the first birthday of my SEEING THINGS column in AJ Blogs. My thanks go to Douglas McClennan, whom I call our Ringmaster, for the opportunity to undertake this adventure and for his support in the course of it–and to my readers, for their faithful interest.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Jennifer Muller / The Works

Powerful, fluent, and downright gorgeous dancers perform hypnotic rituals extolling the human relationship to the wonders of nature. Village Voice 7/13/04

ASHTON CELEBRATION #3

Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

The first week of the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration brought the Joffrey Ballet of Chicago back to New York after a 10-year absence. The company, which used to be resident here, was very welcome. In the old days, even when you weren’t feeling much admiration for it, you often still felt affection for the engaging personalities of its dancers and the troupe’s overall feisty spirit. To be sure, purists in the audience back then would complain about the Joffrey’s imperfect classical technique and the many pop numbers in its repertory (a majority of them by the company’s present artistic director, Gerald Arpino), but they were the first to be grateful for the late Robert Joffrey’s reaching out to choreographers outside the classical domain, such as Twyla Tharp and Laura Dean; his resurrecting “lost” but worthy ballets of the Diaghilev era; and his giving a major American presence to the works of Frederick Ashton. My own happy acquaintance with several Ashton ballets comes solely from their Joffrey Ballet productions. Looking at Les Patineurs, A Wedding Bouquet, and Monotones I and II this past week, I could only wonder, What happened? Not one of the stagings was as good as it should be—and had been.

Les Patineurs, choreographed in 1937 to ebullient music from Meyerbeer, pretends to chart the ups and downs of a winter’s eve Victorian ice-skating party. It has the all the requisite guests: A small spirited ensemble to demonstrate the peculiar pleasure of gliding, especially in tandem, and to react to spills with equanimity. Virtuosi in the form of a young man who’s a veritable whirligig and two sturdy young women who engage in a can-you-top-this? orgy of single-legged turns on pointe. A pair of lovers whose romantic accord is celebrated by a dulcet pas deux. Their locale, the set originally designed for the ballet by William Chappell—all white latticework trellises and hanging paper lanterns—has the charm of a vintage Christmas card.

While the choreography is quietly ingenious enough to fascinate aficionados, Les Patineurs is perhaps the most easily accessible of Ashton’s top-drawer works. Children adore it; people happy to know nothing about ballet succumb to it. But, though it requires of its performers nothing like the subtlety of emotion that must be understood and projected in, say, Enigma Variations, it does demand a secure technique—fluent and graceful in the upper body, covertly powerful in the pelvis and legs, crisp and delicate in the feet. This the present dancers of the Joffrey can’t quite muster. Or let’s say that some of them manage it some of the time, but that this proves insufficient to the occasion. Their vivacity is unquestioned, but it can’t conceal uncertain placement, flaccid footwork, tentative balances, or underpowered action in the thighs, which should be the base of a classical dancer’s turned-out posture.

The present look of the Joffrey’s Patineurs also suggests that there’s no one available to preserve the nuances of shape, rhythm, and tone that are significant in all dancing but absolutely an elemental concern in dancing Ashton. This flaw gravely undermines the company’s production of the 1937 A Wedding Bouquet, a far more sophisticated piece.

David Vaughan, in his Frederick Ashton and His Ballets, tells us what we need to know up front about A Wedding Bouquet: “It is not a narrative ballet, but rather a series of incidents at a provincial wedding in France around the turn of the century, one of those ghastly occasions where everything goes wrong.” The fragments of slyly near-nonsensical text spoken from the stage by a debonair narrator in evening clothes are taken from Gertrude Stein’s play They Must. Be Wedded. To Their Wife. The score, as well as the costumes and set, are from the hand of Lord Berners, who made a career of poetic eccentricity. And Ashton, with his magical fusion of fantasy and craft, gives a bizarre logic to the characters (Julia, for example, who “is known as forlorn”) and their often unfortunate interconnections (“they incline to oblige only one when they stare”; “they all speak as if they expected him not to be charming”), which only the literal-minded would question. But the whole business—sophisticated and amusing—has the fragility of a bubble; if not treated deftly and lightly, it breaks. I recall being enchanted, years back, by the Joffrey’s production. Now, with neither the dancing nor the characters fine-tuned, the piece is apt to appear incomprehensible or pointless to neophyte viewers and sadly coarsened to veteran fans.

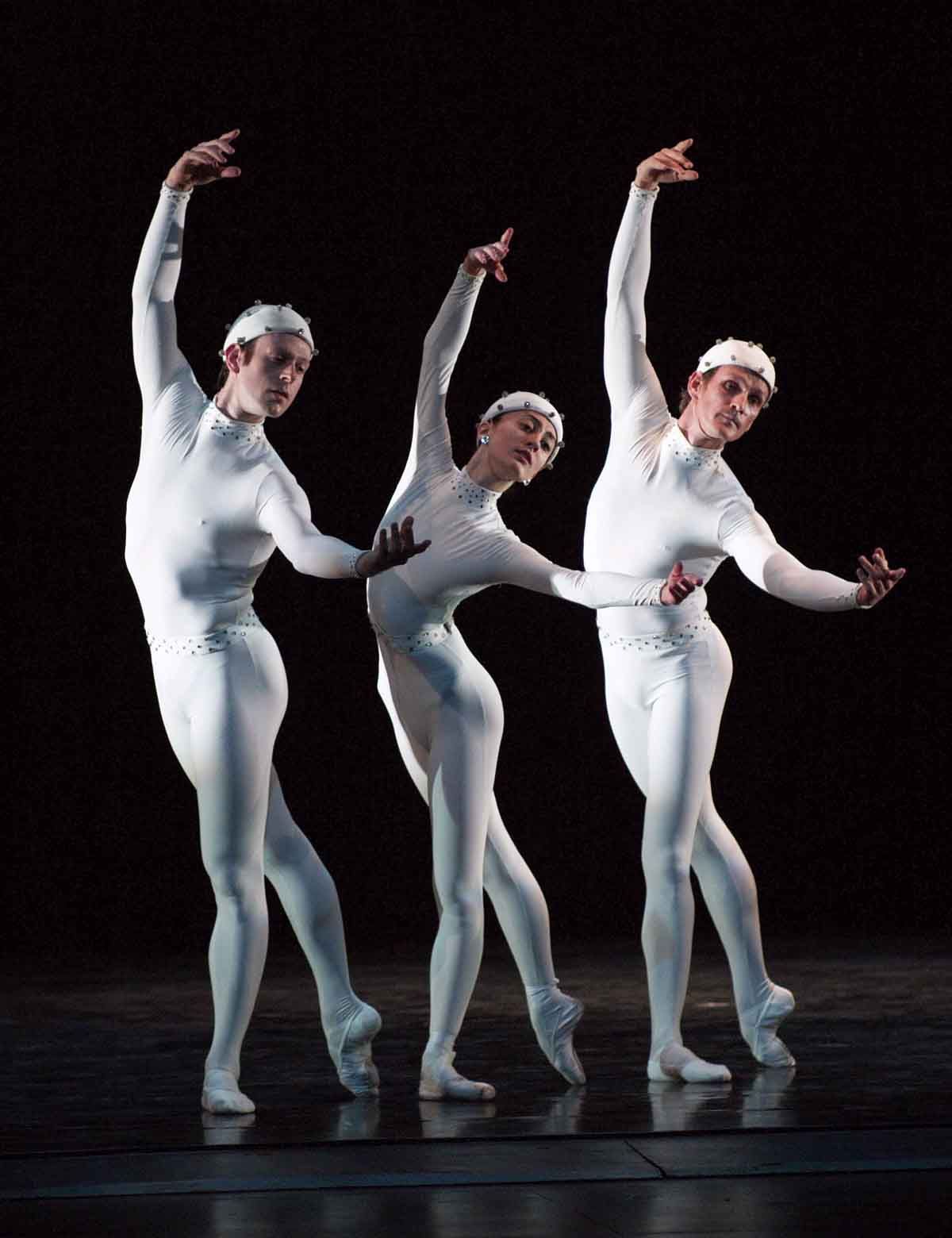

Monotones, the most important of the Ashton works the Joffrey presented, managed to survive a less than perfect treatment. It suffered most from the dancers’ technical inadequacies, but you could still see clearly what kind of ballet it is—celestial. It comprises two trios, now called Monotones I (set to Satie’s Trois Gnossiennes) and Monotones II (set to the composer’s Trois Gymnopédies). Monotones II, for two men and an extremely pliable woman, was choreographed first, in 1965, for a charity gala; Monotones I, for two women and a man, the next year, the earlier piece having been recognized as a miniature masterpiece. Most observers agree that Monotones II (which is occasionally performed separately) is the more sublime of the pair, but the two together are better than either one alone because of the sorcerer’s-mirror way in which they reflect each other in personnel, sculptural shapes, and spatial arrangements.

In each, the dancers are sheathed androgynously in pale skin-tight casings and helmets, here and there highlighted by brilliants, that give them the look of imaginary intergalactic travelers, voyagers to infinity. Their aloof demeanor suggests the divine remoteness and calm of a Buddah. Their dancing, spare to the point of austerity, seems to be a paradigm of purity—or of the very basics of classicism—an illusion that is only enhanced by its being inflected occasionally with eerie acrobatic configurations. It unwinds with hypnotic serenity, and each trio in its entirety, though it looks complete and self-contained, also suggests that it is part of a continuum lying beyond the grasp of mere mortals. The poses of the individual bodies and the ways in which they are grouped—actually touching, separated only by inches, or with generous space between them but still intimately connected visually—is intensely sculptural. At the same time, Ashton seems to be occupied with exquisite linear tracing. “The continuity of his line,” Arlene Croce wrote, “is like that of a master draftsman whose pen never leaves the paper.”

At an ideal performance, Montones doesn’t seem so much choreographed and danced as it appears to be an astonishing glimpse into the workings of the heavens. True, the center did not hold in the recent performances, but it looked as if the dancers and their coaches understood and honored the nature of the ballet and were attempting to do it justice.

Under Robert Joffrey’s leadership the Joffrey company annexed such a goodly number of Ashton works and presented them so gratifyingly that I, for one, would contend that it made a promise to its audience, a promise I ardently hope it will go about keeping.

Note: Having mentioned David Vaughan’s Frederick Ashton and His Ballets (Knopf, 1977) in all my postings to date on the Ashton Celebration—because I’m forever consulting it—I feel obliged to say that another ambitious Ashton tome exists: Julie Kavanagh’s Secret Muses (Pantheon, 1996). It contains some useful information, to be sure. However, it is maddening to read if it’s Ashton’s ballets you want to know about. It continually insists upon sliding without warning from the subject of Ashton’s work to his private life, which—unlike his art, in no way unique—is made to appear by turns seamy, frustrated, and pathetic, a fitting subject for a Boris Eifman. I’ve nicknamed Kavanagh’s book “Sir Fred in Bed.” I think of Vaughan’s book as “the Bible.”

Photo credit: Herbert Migdoll: Members of the Joffrey Ballet in Frederick Ashton’s Monotones II

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Correction: In my July 7 posting, Ashton Celebration #1, I recommended standing room tickets as a budget-conscious way of seeing the Lincoln Center Festival’s Ashton Celebration, currently at the Metropolitan Opera House. (Standing room tickets for American Ballet Theatre’s recent season at the Met cost $20; the advertised price range for Ashton Celebration tickets is $150 – $35.) A reader has since alerted me to the fact that standing room has not been made available for the Ashton Celebration. Representatives of the LCF tell me that (1) students of any age with a valid current student i.d. card can buy a single or a pair of tickets in the Family Circle at $20 per ticket, applying for them in person at the Met box office, and that (2) the Playbill Club \http://www.playbill.com/index.php\ is offering moderately reduced prices on $50 and $35 tickets.

ASHTON CELEBRATION #2

Lincoln Center Festival 2004: Ashton Celebration / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / July 6-17, 2004

The second night of the Ashton Celebration featured two dances, both Birmingham Royal Ballet productions, in which the choreographer operated in his free-flowing “barefoot” vein, presumably with Isadora Duncan as his muse. The legendary primogenitor of modern dance was surely past her prime when the 17-year-old Ashton witnessed a handful of her performances in London, but she nevertheless made a tremendous and lasting impression on him—through her musicality, her sense of plastique, her voluptuous weighted quality, her resonance in stillness, and the sheer charismatic force of her conviction.

The second night of the Ashton Celebration featured two dances, both Birmingham Royal Ballet productions, in which the choreographer operated in his free-flowing “barefoot” vein, presumably with Isadora Duncan as his muse. The legendary primogenitor of modern dance was surely past her prime when the 17-year-old Ashton witnessed a handful of her performances in London, but she nevertheless made a tremendous and lasting impression on him—through her musicality, her sense of plastique, her voluptuous weighted quality, her resonance in stillness, and the sheer charismatic force of her conviction.

Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan started out as a little nothing, a pièce d’occasion. From his recollections of Duncan, enlarged by the evocative action drawings artists had made of her—not attempting to replicate Duncan’s own simple choreography but freely extrapolating from it—Ashton set a single waltz on the superb dancer-actress Lynn Seymour for a gala in 1975. It was recognized as a gem and, the following year, he expanded the material into a suite, which entered the repertory of the Royal Ballet.

Seymour was extraordinary in the role. Even photographs, which inevitably diminish the vitality of the dancing they record, show that. One, by Peggy Leder, seizes the moment in which the Isadora figure rushes straight forward toward the audience, arms outstretched, rose petals cascading from her hands, head flung back to expose a strong, sensuous throat, the advance of the body led by a magisterial foot that confidently acknowledges gravity’s claim.

The BRB’s staging was danced by Molly Smolen, who had the immense good fortune to have Seymour coach her in the role. The result was glorious. Smolen moves with exorbitant energy, capturing the lion-hearted quality we associate with Duncan. What’s more, she makes the movement look impetuous; for a moment you think she might be inventing it on the spot. I suspect this quality characterized Duncan’s performances, which may well have encompassed a certain measure of improvisation. Running about the stage in a curving path, trailing behind her a huge swath of fabric that echoes the glowing peach hue of her Grecian tunic, Smolen seems to have turned herself into all things that ripple with life: wind, waves, flames. At times, she’s Dionysian, the incarnation of primal sexual instincts. Elsewhere, in repose, she seems to find the still center in which a single person can imagine herself to be the heart of the universe.

Unlike Duncan, and unlike Seymour, who danced with generously fleshed bodies, Smolen has an upper body that appears as slender as a stripling’s, and her arms retain some of the charming angularity and awkwardness of adolescence. Astutely, she uses this deviation from the generic Isadora image to her advantage. She lets the gaucheness set off the prevailing voluptuousness of the material and, with it, suggests something of the stubborn, single-minded rebelliousness, usually confined to impulse-driven youth, that characterized Duncan’s personality and actions, onstage and off, throughout her life.

Much credit for the pleasure and excitement Smolen generates in this Ashtonian gem is due to Seymour—for serving as mentor to an interpretation so valid for the ballet yet so unlike her own.

Dante Sonata, rescued from oblivion on the initiative of the BRB’s director, David Bintley, was choreographed in 1940, as Britain waited for the bombs of World War II to obliterate the happier life it once knew. A somber mood due to the recent death of his mother augmented Ashton’s response to, as he put it, “the whole stupidity and devastation of war.” (On another occasion, he used the word futility.) So the ballet’s juxtaposition of the Children of Light and the Children of Darkness is no good-guys-vs.-bad affair, but rather a lose-lose situation, in which, though the Dark figures are patently the aggressors, both tribes are ravaged and all but destroyed. Although the work is, admittedly, something of a period piece—with lots of Massine-derived, Robert Helpmann-style expressionism in it—it is piercingly relevant today. It should be required viewing, for instance, for anyone participating in the upcoming national conventions of our major political parties, alternating in repertory, perhaps, with Kurt Jooss’s The Green Table.

The ballet is based on the Inferno and Purgatorio sections of Dante’s Divine Comedy and set to music by Lizst that refers to the Dante via a poem by Victor Hugo. The choreography, like the costumes and backdrop by Ashton’s beloved collaborator Sophie Fedorovitch, are influenced by celebrated illustrators of Dante: William Blake, Gustav Doré, and John Flaxman. The female Children of Light are visions of innocence in unadorned translucent white gowns; their male partners, princes of purity, complement them in snowy chemises with blouson sleeves and immaculate danseur noble tights. The Children of Darkness favor black webbing and grimaces that transform their faces into ferocious (or is it agonized?) masks. The choreography owes most, however, to Isadora Duncan, not simply because most of the dancers are barefoot and the women’s long hair is unbound, but also—and primarily—for its emotion-invoking plasticity and its tidal surges of movement.

“What one mostly remembers from Dante Sonata,” David Vaughan writes in Frederick Ashton and His Ballets, “are its images of shame and suffering, turmoil and torment.” I can’t put it better and would merely add to it notice of the effective patterns Ashton designed for the warring groups—now starkly geometrical, as in Martha Graham’s 1931 Primitive Mysteries; now linked and braided as in Bronislava Nijinska’s 1923 Les Noces. Beyond that, I recall particularly the sheer pictorial beauty of the several ways in which the participants shield their faces, depicting grief, and the odd yet very apt things occasionally done by a single figure suddenly sprung from the ensemble—a woman, for example, nearly berserk with anguish, thrashing the air with her arms as she runs, as if beating frenetically on a giant invisible drum. This aspect of the choreography eerily prefigures certain traits in Mark Morris.

As I’ve indicated, Dante Sonata works as a polemic piece as well as on a purely aesthetic plane. Concerning the latter, the most intriguing aspect of the ballet may be its intensely pictorial nature. It ends, for example, with the simultaneous crucifixion of the male leaders of the Darkness and Light clans, but the shock and horror of the action is muted by the fact that the scene makes you think, first and foremost, of paintings of the subject you’ve viewed in the medieval and Renaissance sections of the world’s great museums.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper: Molly Smolen in the Birmingham Royal Ballet’s production of Frederick Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan

© 2004 Tobi Tobias