New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 27, 2004

American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / May 10 – July 3, 2004

NEW YORK CITY BALLET: A PAIR OF NEW WORKS FROM PETER MARTINS

I. EROS PIANO

The subtler and more engaging of the two new works by the New York City Ballet’s artistic director, Peter Martins, the trio Eros Piano is set to John Adams’s delicate and complex music of the same name. A flood of luminous color greets the eye as the piece opens. Mark Stanley has suffused the vast bare stage with a glowing turquoise light that suggests an underwater universe. First one woman (Ashley Laracey) picks her way on pointe along a lateral path so far upstage she reads as a shadow, a figure there and yet (do I wake or dream?) not there. Just as she vanishes from view, Nikolaj Hübbe, a substantial figure bathed in a golden glow, traces a parallel path downstage. Then he’s gone and a second fragile figure (Alexandra Ansanelli) appears, she too traveling laterally, so that we seem to be witnessing a panorama-in-time, with the women figments of our imagination and of the man’s as well. To add to the illusion, Holly Hynes has dressed the women in aquamarine unitards, one a paler shade, the other more intense. Hübbe is sheathed in a blue-green tint so faint it looks like ice.

Eventually the three get together, the man first with one woman, then, after she drifts away from him, the other, and finally—this has a wonderful theatrical-shock effect—with both. As a fellow might expect, partnering mermaids, the women’s bodies behave as if they’re infinitely malleable. These circumstances give Martins a perfect opportunity to explore one of his prime areas of curiosity and expertise, convoluted partnering. If he has used it with excessive ingenuity elsewhere, in this instance it is appropriate and lovely. Hübbe manipulates the acquiescent women into all sorts of baroque shapes, wrapped around him like clinging seaweed or poised on the ground as if resting for a moment on the floor of the sea until a passing wave escorts them back to the surface.

Hübbe and Martins both being Danish-born, trained in the school of the Royal Danish Ballet and principals in its company before leaving home for Balanchineland, I couldn’t help thinking, as I watched Eros Piano, of Bournonville’s Napoli, widely considered Denmark’s “national ballet.” In the Blue Grotto scene that constitutes most of its second act, the appealingly plebian hero, Gennaro, enters the dangerous enchanted underwater realm in the hope of rescuing his beloved fiancée, Teresina, lost to the waters when their little boat capsized in a storm. Alas, the demon running the place is busy transforming her into a naiad. Initiated into the sisterhood of water nymphs that he holds in thrall, Teresina will be doomed to lure splendid young men away from real life and its responsibilities into a realm of ceaseless but monotonous pleasure. The key connection between Napoli’s Blue Grotto passage and the situation Martins sets up in Eros Piano is the fact that Gennaro can’t recognize Teresa in her replica-naiad state—she might be any one of those alluring girls gliding around him—nor she (in her mesmerized state) him.

Nineteenth- and 21st-century ballet being obedient to different rules, Napoli ends happily, with Gennaro and his Teresina, having triumphed over seductive evil, reunited in sunlit terra firma reality, whereas Hübbe is finally abandoned by both women—true to their nature (or to the nature of postmodern relationships), they just float away. As the curtain cuts him off from our sympathy, he stands alone, bereft of companionship or enlightenment as to his plight.

Even apart from its chamber-scale cast, Eros Piano is a small piece, unpretentious in its ambitions, focused on filigreed detail. It might be still more absorbing in a theater of more modest proportions. I would like to see it again. Meanwhile I wonder what connection, if any, exists between this piece and Martins’s Chichester Psalms, with which it’s paired on the current season’s programs. Does it lie in a coupling of opposites—Eros and Agape, profane and sacred love?

II. CHICHESTER PSALMS

Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms—an arrangement, for orchestra, chorus, and boy soprano, of familiar passages from the Old Testament—can be understood as urging, in appreciation of life, the wisdom and reconciliation that will quell factional strife and bring about a holy state of peace. Perhaps Martins decided to stage this score because of the turmoil rife in the world today. Both casts for his setting, named for the music, are led by a fair-complexioned woman and a dark-skinned man. (Carla Körbes and Amar Ramasar did the first performance; Dena Abergal and Henry Seth have also been cast.) The pair act as guides in the cause of calming internecine warfare through a realization that people are more alike than they are different. Ramasar, a gentle, deeply expressive dancer, is the very image of compassion.

The ballet’s opening image, a formal tableau of mixed chorus and dancers ranged in a wide tiered arc, announces the solemnity of the piece. The performers’ black and white costumes (by Catherine Barinas) refer to choir robes and ancient Middle Eastern dress. The female dancers’ white gowns lean toward the Grecian mode, which makes their pointe shoes look incongruous (and suggests that the ballet vocabulary is not the perfect language for the task at hand). The male dancers’ costumes, picturesque swirls of black, owe something to Martha Graham (whose own vocabulary is usefully raided to add a bit of force and expression to the proceedings).

Apart from the two principals, the dancers move in chorus. The most dramatic section has the men paired off in combat, with the women, midway, running lyrically through their midst to quiet the conflict—agents of succor, advocates of harmony. The principals, who seem to be loving partners with regal dignity, simply lead their tribe toward its quiet epiphany.

Overall, the choreography is more like an illustration of principles than an enactment of them. It is also curiously deficient in force and invention. Modern dance choreographers and ballet choreographers with modernist leanings have done more effective work in the choral mode. To name a few: Doris Humphrey, in the architecturally driven New Dance; Martha Graham, in Primitive Mysteries, where the ensemble, with its inexorable tread, becomes the chief character; Bronislava Nijinska, in Les Noces, which vigorously embodies the force of community evident in Stravinsky’s score. Martins’s effort, essentially pallid and banal—the ensemble linking hands to promenade in a snaking chain, and so on—allows your attention to wander to the disagreeable question of whether or not Bernstein’s music wants, or even really permits, a visual complement. I suspect that it doesn’t.

The score, conducted by Andrea Quinn, was persuasively sung by the Juilliard Choral Union (directed by Judith Clurman) and the thirteen-year-old James Danner, who duly produced some of those unearthly tones that reinforce the beliefs of the faithful and give religious skeptics second thoughts.

AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: GILLIAN MURPHY

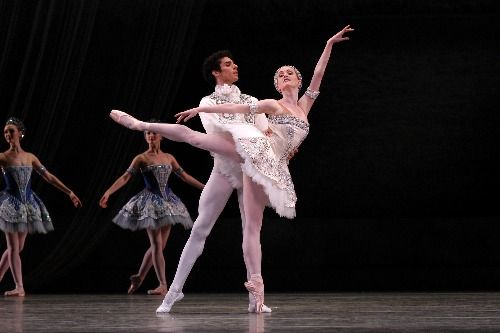

Gillian Murphy, who dazzled this past week in Ballet Imperial, is a ballerina in every fiber of her being. Her own dancing is bold, confident, and magisterial; what’s more, she looks as if she’s the animating force behind the whole ensemble. Self-contained, immune to flourishes of ego, she simply takes charge of everything that’s happening on stage, making the entire ballet cohere.

By a slight re-angling of her body in partnered adagio, she shifts from one potent image to another. Here she’s a princess in a tragedy of love, the next moment a bird poised for flight—an icon of freedom. She’s too singular and formidable a physical personality to qualify as a natural actress—she’ll have to approach drama-dependent roles obliquely, as she did with Hagar in Tudor’s Pillar of Fire. Perhaps her innate ability to create telling images—physical metaphors, as it were—will prove sufficiently theatrical in itself.

Tall and large-boned, with a striking face (often compared to Bette Davis’s) and phenomenally adept technique, she seems, sui generis, powerful and regal. The next time company and choreographer find themselves casting about for a subject as they set out to spend zillions concocting a latter-day multi-act, lavishly decorated story ballet—these items may not advance the cause of dance but they often sell tickets—they’d do well to think of Murphy as Queen Elizabeth I (also an imperious redhead) or Catherine the Great.

Photo credit: Marty Sohl: Gillian Murphy and Carlos Molina in the American Ballet Theatre production of George Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial

© 2004 Tobi Tobias