Tiffany Mills tells us that out-of-control force and skewed perceptions belong to us all. Village Voice 6/29/04

Archives for June 2004

BALLET GALORE: WEEK #8

New York City Ballet: Boris Eifman’s Musagète, world premiere June 18, 2004

For reasons too discouraging to explore, the New York City Ballet commissioned a work from Boris Eifman for its year-long Balanchine centennial celebration, now winding down. And Eifman came up with Musagète (Leader of the Muses), a 50-minute extravaganza that–despite its appalling notions of choreography, biography, and their possible relationship–claims to be a homage to the master. This is an event that could only have occurred over Balanchine’s dead body. The Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg is much acclaimed in its home town (the city that bred Balanchine) and it has certainly been a hit in its City Center appearances of the last half dozen years, relished by an audience packed with Russian émigrés. But Eifman operates from an aesthetic that’s the antithesis of Balanchine’s–long on lurid melodrama and gimcrack sentiments, short on musicality, structure, steps, and classical decorum. Following are my notes. (It’s o.k. if you want to stop reading now. Really.)

The musical selections that make up the score–substantial excerpts from Bach, a snippet of Georgian choral singing, and an infusion of Tchaikovsky to wind things up–begin with the Bach Paul Taylor used for the dark-night-of-the-family’s-soul section of Esplanade. Eifman gives us a lone man (Robert Tewsley), in generic black trousers and white t-shirt, sitting on a chair, head bowed, in what looks like a prison. We’re talking major depression here. Or worse. Eventually this troubled protagonist (let’s call him Mr. b, after the Big B he represents) points his finger skyward. Maybe this means something–but what? Emerging a little from his gloom, he stands to execute the tendu demonstration famous from the Cartier-Bresson photo that the NYCB adapted for its centennial logo. Retrieved verticality launches him into an anguish-in-the-throes-of-creation solo in which he’s half on, half off his chair, which conveniently turns out to have wheels. (Never mind that Balanchine was known to keep his personal griefs private and his behavior in the studio briskly professional and productive.) An attendant appears and tries to calm him. Hey, wait a minute. Is this Stygian cavern not a prison but an asylum? Has Eifman confused Balanchine with Nijinsky gone mad?

Next, an opaque black backdrop rises just enough to reveal a line-up of pairs of feet in pointe shoes working away in frisky, nimble unison. The drop then rises to reveal, full figure, the owners of the feet, inexplicably clad in performance-ready white tutus to perform their daily exercises at the barre. The idea is based on an actual formative event in Balanchine’s youth. Still a pupil at the renowned Maryinsky academy, he broke school rules to peer into a studio where the company’s ballerinas were practicing and was fascinated–riveted–by the sight of their footwork. Eifman’s treatment of the event, however, is lifted from Harald Lander’s eternally popular middle-brow entertainment Études, a debasement true to his taste.

One by one the young ladies advance into the center space to be corrected and manipulated (yup, here come the sexual overtones) by Mr. b. He shows them what he wants them to do, choreography-wise, enjoying little flirtations on the side. This already misguided section culminates with Mr. b choreographing the opening gestures of Serenade–the raised arm with the hand shielding the face from the light, the feet snapping from parallel position into a turned-out first.

Back to the blackness and the chair, but now Mr. b enjoys the company of a single “special” woman (Wendy Whelan) sheathed in a black practice outfit enlivened by sparkling paillettes on the bodice and on a matching snood. Mr. b veers between sculpting her–seeing what contortionist grotesqueries her body is capable of–and making love to her. This is Eifman’s “advanced” notion of the adagio pas de deux.

At the performance, I was trying to figure out which of Balanchine’s early muses/private-life partners Whelan might represent. Tamara Geva? Alexandra Danilova? Vera Zorina? They were all glamour girls. Subsequently I caught up with a New York Times piece by Sylviane Gold that reports Whelan’s saying she understood herself to be the incarnation of Balanchine’s cat Mourka. The celebrated feline was photographed by Martha Swope as the choreographer put her through motions that looked very much like spectacular dancing. Go know.

Anyway, a fellow in black practice clothes (chic, like Whelan’s) strides purposefully by and, uh-oh, Ms. Muse seems to like him better than she likes Mr. b. The new pair disport themselves acrobatically, their duet briefly enlarging into a pas de trois, but Mr. b quickly drops out of this impossible affair and despairs, while Mr. X carries off the muse. (Have we somehow skipped ahead to the rupture between Balanchine and his most compelling égérie, Suzanne Farrell, upon her marriage to a NYCB dancer? Surely few men would be so despairing over the loss of a cat, no matter how lithe and obliging a dancer it was.)

A whole flock of girls in black studio togs kindly arrives to comfort Mr. b. One even covers his eyes à la Serenade‘s Dark Angel. (Aficionados in the audience are registering the quotes from the masterworks almost audibly, and Eifman obligingly selects only obvious ones. Have I mentioned Agon?) Then, mercifully, the lights come up full and Mr. b goes back to his proper business of choreographing, moving from the women to a gaggle of men, then meshing the two ensembles. Suddenly, from their midst, Mr. b grabs one of the anonymous boys and matches him with one of the anonymous girls. (“Notice me! Notice me!” was the eternal cry from Balanchine’s acolytes, and the choreographer was swift to spot potential and groom it.) But now, abruptly, with a rough push and pull, Mr. b changes one boy for another. This chance of a lifetime that fizzles happens too fast for its implications to be explored, as is perhaps for the best. Mr. b retreats to the back of the stage and stands impassive, arms folded, as if, having pressed the “On” button, he could let the choreography evolve on its own. From the frenetic look of the proceedings, he’s pressed “Fast Forward.”

Lo and behold! a girl in a rosy girlish dress runs in and (here comes Serenade again) falls down. Mr. b gives her the balletic equivalent of the kiss of life–the God-touching-his-finger-to-Adam gesture that Balanchine co-opted from Michelangelo for Apollo. (What can we learn from this? That the quality of borrowings depends not on the material borrowed but on the sensibility and craft of the borrower.) The girl is Alexandra Ansanelli at her most kittenish (no, not like Mourka, Mourka was classical in repose and a hoyden in motion). The pretty-in-pink girl and Mr. b fall in love, enjoy a mutual accord blissfully free from anguish, until . . .

The happy couple finds itself rushing through a matrix of women looking mid-century modern dance-ish in long, severely cut black skirts. Has Martha Graham been invited to create a work for Balanchine’s company? (This did happen once, the result being the now discarded first half of Episodes, but that experiment was Lincoln Kirstein’s bright idea; Balanchine had no use for modern dance.) Or is this one of those Russian premonitions of doom? Suddenly Mr. b is back in his peripatetic chair, despairing, his watchful attendant ever-solicitous. (Eifman seems to find the idea of solitary incarceration piquant and insanity theatrically picturesque. I haven’t the least objection to morbidity on stage, but I prefer mine unDisneyfied.)

Ansanelli returns, playful as ever, to engage Mr. b in a duet that’s part contortion, part making out, when–bam!–Fate strikes her down, robbing her not merely of an inherent grace that ballet training has honed to perfection, but of her very mobility. She collapses in grotesque postures. Tanaquil LeClercq, felled by polio. A death figure out of Ingmar Bergman’s Seventh Seal drags her out of Mr. b’s sight and life on a long swath of inky cloth. (Never mind that Balanchine remained married to LeClercq for a good long time after her illness struck and that she lived, gaming coping with her disabilities, for many years after they parted. Never mind that she was in no way an Ansanelli type–either physically or in stage persona. LeClercq was all long-legged rakish elegance, the epitome of intelligence and wit, with an uncanny capacity for poetic suggestion. The well-nigh criminal tastelessness of Eifman’s depiction of her tragedy would have driven me out of the theater had I not been sitting in the middle of a long row–and obliged, as a journalist, to see the performance through.)

So . . . where were we? Mr. b, as is his right, succumbs once again to grief. A phalanx of men arrives to energize him, followed in short order by a matching female contingent; the choreographer’s raw material, as is its right, is urging him to get back to work. No sooner has he complied than, among them, he notices the magnificently long-legged, sensuously supple Maria Kowroski and seizes her for his own. Suzanne Farrell, of course. The company simply fades away, leaving Maria/Suzanne and Mr. b alone in the dark with a ballet barre just long enough for two. He discovers her enormous physical and emotional resources and the rest is history. The barre (itself inclined to motion, like its cousin, the chair) bears witness to shenanigans no barre should have to endure. At their conclusion, Mr. b lies spent. The lady vanishes. Though tasteless (as Eifman’s work is chronically), this business is not as vile as the polio episode. Nevertheless, as balletic orgasms go, it doesn’t hold a candle to the climax of L’Après-midi d’un Faune.

A fog blows in. Mr. b indulges in a little modern dance floor work to some religious-sounding choral music (Georgian, in reference to Balanchine’s ancestry). Mr. b, it appears, has entered an altered state. From above, a pastel rainbow of light beams plays on the swirling mist. Gaze cast to the heavens, Mr. b splays his body along the tipped barre that, moments before, served as a bed for ostensible voluptuous pleasure. (It looks no more comfortable than Noguchi’s precarious bed for Oedipus and Jocasta in Graham’s Night Journey, but let that pass.) Now it’s a death bed, and its occupant is experiencing visions.

Balanchine treated his own death choreographically at least twice–depicting the last moments of the visionary Don Quixote in the ballet of the same name (sometimes performing the role himself), where the bed actually elevates its expiring tenant, and in the profoundly moving pageant-like setting of Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique. Both treatments depend on the highly colored imagery and impulse to ecstasy that one might expect from an adherent of the Russian Orthodox faith. Yet even viewers who found the material over the top could see that it poured from a font of simple, indeed naked, sincerity, and that, like everything else Balanchine did, it was exquisitely balanced in a larger context. Eifman’s Mr. b, I’m afraid, expires in tawdry-thrills mode. But the show’s not over until the finale.

Dazzling lights. Chandeliers. A mass of women in snowy zircon-studded tutus, fetching little tiaras, and partners to match, madly churning out what might be a faultily translated, phoned-in version of the finale of Symphony in C–or is it Theme and Variations? Or Ballet Imperial? Amid the hectic traffic, hierarchy prevails, as it must in classical ballet. Whelan and Ansanelli, partnered, respectively, by Nilas Martins and Benjamin Millepied, are relegated to soloist status in favor of Kowroski, who, as the channeled image of Farrell, must reign supreme. Squired by Stephen Hanna (Mr. X, see above), she egregiously exaggerates whatever she has in common with Farrell, who, in real life, is no longer welcome at the New York City Ballet in any role, but whose dancing remains indelible. Raked over though one’s sensibility may be, exhausted as one’s eyes are at this point in Eifman’s travesty, one should not miss the second quote from Études that turns all the dancers into silhouettes.

Then, melodramatic flashes of light, and the late Mr. b, now in evening clothes (no doubt de rigueur in Paradise), moves among his dancers. They all bow to something unseen, then cheerily carry on their work like the pros they are. By now, though, they look like automata.

Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

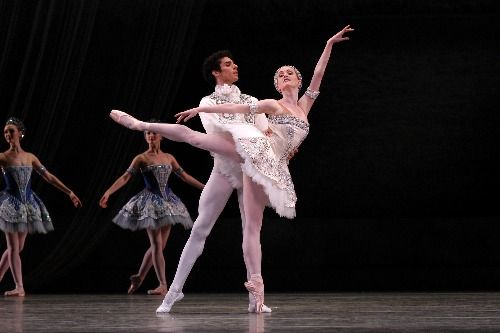

Photo: Paul Kolnik: Alexandra Ansanelli and Robert Tewsley in Boris Eifman’s Musagète

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Midsummer Night Swing

No matter that both your feet are lefties. Midsummer Night Swing will get them stepping and gliding with rhythm, grace, and spunk. Village Voice 6/22/04

School of American Ballet 40th Annual Workshop Performances

Most delightful was Susan Pilarre’s staging of two chunks of Union Jack, in which technically brilliant incipient stars let themselves go, showbiz-style, with terrific humor and verve. Village Voice 6/22/04

Parsons Dance Company

David Parsons’s choreography played second fiddle to the live music from the Ahn Trio that accompanied it. Village Voice 6/7/04

CHANGE OF SCENE

Stephan Koplowitz: The Grand Step Project / various locales, NYC / June 15-28, with multiple performances on each date; for specific locations, dates, times, and travel directions, go to: http://www.dancinginthestreets.org/season/grand_step.html

Dancing in the Streets, which springs choreography from the prison of conventional theaters, celebrated its 20th anniversary by commissioning the site-specific specialist Stephan Koplowitz to tackle half a dozen celebrated New York City staircases. The result was The Grand Step Project, which I visited at the location most familiar (and dear) to me, the broad steps fronting the imposing Beaux-Arts façade of the New York Public Library at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street–the Lion Library as it’s affectionately known, being guarded by the magisterially leonine marbles, Patience and Chastity. Overlooking Fifth and thus offering a fine view of the passing parade of life in midtown, these steps are often inhabited–at least in decent weather–by construction workers and office workers (chatting desultorily as they consume their brown bag or take-out lunches), students, lovers, tourists, and folks whose feet or spunk have simply given out en route.

The steps comprise a pair of long and wide, wide, wide flights separated by a generous flat plaza. The performance Koplowitz designed–15 minutes of choral music (on this occasion from the New York Choral Society, rendering feisty spirituals) followed by 15 minutes of dancing–gamely used the flat expanse for an empty zone between action and audience and confined the dancers to the upper flight, which is broken only by a single meager ledge.

The beginning of the dance was spectacular. Dozens of young people in summery street clothes spilled from behind the library entrance’s massive pillars, stretched out on the stairs as if lying in their beds or floating on a lake, and proceeded to roll down the steps until the whole staircase looked as if it had turned to roiling flesh.

The thing about a staircase, though, is that, once you’ve gone down, there’s no place to go but up, and so the dancers stood and did so, which was something of an anti-climax. Apart from a repeat of the lava-pouring-down-the-mountainside roll (compelling even the second time around), the balance of the dance consisted largely of the figures’ grouping and regrouping in formal clusters and making semaphoring sorts of gestures with their arms. Some contrast to this material was duly provided by the ensemble’s forming a human frame for a few soloists and occasionally coupling up for a little jiving, even a lindy-style lift or two, though there wasn’t much space on the stairs for letting go.

Given the circumstances–the staircase venue, the outdoor location (which invariably diminishes dramatic impact)–the massed-choir tactics were destined to work best. They would work even better, I think, if the arm gestures with which they’re embroidered had more full-bodied power behind them. As they’re performed now, the hieratic motions are made with limbs that look too fragile and fingers that seem too delicate to create sufficient impact. The same moves would register more eloquently if sprung from the gut, with visible energy and weight.

All in all, though, the performance was both ambitious and appealing. This sort of undertaking is a major organizational challenge, yet it was presented as the kind of thing that might just happen serendipitously in a big, crazy town where art counts and imagination flourishes. I–and, apparently, the crowd that gathered and stayed–found it compelling enough to overcome the distraction of the day’s weather (temperature in the nineties, humidity that made your palms stick together when you tried to applaud). Most important, its premises proved to have staying power.

The show over, I fled around the corner to the subway for a nice cool local train to the Upper West Side. As I went down the MTA staircase, it suddenly came alive for me. The steps here are slate gray, scored into a diamond pattern. Because of their composition, millions of displaced stars seem to twinkle from the dark matrix, defying the blobs of used chewing gum, the smoldering cigarette butts, and god knows what else New Yorkers cast away and crush with their relentless traveling feet. I was conscious of myself going down the steps, that utterly pedestrian function taking on the fascination of art. I reacted to the appearance of a lone climber-up (with her sienna skin and her flamboyant red dress, she took on the grandeur of a diva making an entrance in a gorgeously melodramatic opera). I registered the decreasing distance between us–until we passed each other and, as if by some infallible magic, the space between us began to stretch out again.

I thought about other steps, among them the infinite number I had climbed the day before with a patient but weary granddaughter in tow, when the escalator at the elevated 125th Street station on the Broadway line froze into staircase mode. “Climbing and climbing to reach the subway in the sky,” I said to encourage the four-year-old with the wondering gentian-blue eyes and the corn-silk hair curling into tendrils from the heat. Pale and slender, her bare legs labored to carry out the necessary task. “We’re climbing all this way up to catch the train, and the first thing it will do is take us underground. Isn’t that odd?” I asked the silent child, who allowed me a flicker of a smile and persisted in her arduous ascent–Heidi takes Manhattan.

I assume that creating a heightened awareness of the environment and ourselves as performers in it, is more or less Koplowitz’s intention.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

BALLET GALORE: WEEK #7

SCHOOL OF AMERICAN BALLET 40TH ANNUAL WORKSHOP PERFORMANCES

Juilliard Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / June 5 & 7, 2004

Persisting in its unwieldy low-key name (see above), Workshop infallibly provides a bright spot in the dance-world calendar. A yearly showcase of the august academy’s students, the event consists of matinee and evening performances on a Saturday and a gala evening the following Monday (same program, with varied casting at the top). And then it’s gone forever—apart from the archival videotapes made since 1980 by Virginia Brooks, which can be viewed with permission from the Balanchine Trust. A look through those archives reveals a quarter century’s worth of nascent stars, to say nothing of dancers who would become distinguished soloists and stalwart members of the ensemble—at the New York City Ballet (the school’s parent company) and with other troupes cross-country and abroad.

As just about everyone in Workshop’s audience is aware, it was George Balanchine who, with Lincoln Kirstein, brought SAB into being—even before they established the forerunners of the NYCB. Legend has it that Balanchine insisted, “But first a school.” In honor of the 100th anniversary of the choreographer’s birth, this year’s program was dedicated solely to works from his hand: Serenade, the first ballet he created in America; the Ballabile des Enfants from Harlequinade (which gives stage experience, an essential component of dance training, to pupils still some years away from their teens); Le Tombeau de Couperin (a tribute to the “anonymous” dancers of the ensemble); and excerpts from the Hail, Britannia! extravaganza Union Jack. At the conclusion of the last piece, where a stageful of dancers usually performs a tour de force of synchronization, spelling out “God save the Queen,” each one armed with a pair of perky twin-triangled semaphore flags, the message instead read: G-E-O-R-G-E B-A-L-A-N-C-H-I-N-E. And instead of the British flag being flown in behind the smiling signalers, down came the Cartier-Bresson photo of “Mr. B,” every SAB student’s godfather, demonstrating the correct placement of the foot in tendu, a basic that classical dancers repeat daily, striving to step a millimeter closer to perfection, from their first class to their retirement.

Potential-star spotting is part and parcel of Workshop. For me, two young women, polar opposites in type, stood out this year: Tiler Peck and Kaitlyn Gilliland. Peck, a 15-year-old from California, is a diminutive bundle of athletic energy, with a projection that’s absolutely electric. In Serenade, she’s so eager to exercise her technical brilliance that she prevents the atmosphere of the piece from accumulating around her. As a rollicking sailor in Union Jack, though, she’s perfect. With her exuberance and assurance, her evident joy in being who she is and doing what she’s doing, she could carry a Broadway show on her own.

Gilliland, just turned 17, comes from Minnesota and from a distinguished matrilineage. Her grandmother, the late dancer and choreographer Loyce Houlton, founded Minnesota Dance Theater, blending the purity and lyricism of classical ballet with the deep texture of modern dance. Her mother, Lisa Houlton, who now runs that company, was herself a lovely dancer schooled in both modes. Gilliland, however, might be a changeling child. She seems to belong entirely to the ballet domain, indeed to a particularly rarefied part of it. Exceptionally tall, exceptionally slender, her small head poised like a jewel on her long neck, her spine as flexible as a young willow, she’s an ethereal, otherworldly creature. As the “Dark Angel” in Serenade, she seems to exist in a dream that is half the creation of Balanchine and Tchaikovsky, half her own fantasy. Even heading up the leg-flaunting chorus of Wrens in Union Jack, She manages to remain a little shy, luminous in her innocence. She will remind veteran observers of Allegra Kent.

Gilliland, just turned 17, comes from Minnesota and from a distinguished matrilineage. Her grandmother, the late dancer and choreographer Loyce Houlton, founded Minnesota Dance Theater, blending the purity and lyricism of classical ballet with the deep texture of modern dance. Her mother, Lisa Houlton, who now runs that company, was herself a lovely dancer schooled in both modes. Gilliland, however, might be a changeling child. She seems to belong entirely to the ballet domain, indeed to a particularly rarefied part of it. Exceptionally tall, exceptionally slender, her small head poised like a jewel on her long neck, her spine as flexible as a young willow, she’s an ethereal, otherworldly creature. As the “Dark Angel” in Serenade, she seems to exist in a dream that is half the creation of Balanchine and Tchaikovsky, half her own fantasy. Even heading up the leg-flaunting chorus of Wrens in Union Jack, She manages to remain a little shy, luminous in her innocence. She will remind veteran observers of Allegra Kent.

I also liked Rachel Piskin’s dulcet lyricism in Serenade. Piskin, who is 16, isn’t as striking a type as Peck and Gilliland; she’s more the norm—but it’s a lovely norm that she embodies, and she seems almost guaranteed a rewarding career.

As for the men, their very number is noteworthy. Could it be that America has finally matured enough culturally to allow its young men to dedicate themselves to classical dancing? In the Harlequinade children’s divertissement, some of the “boy” roles that, of necessity, have long been played by girls en travestie, are now gender-correct in their casting, and it does make a difference. Elsewhere the guys representing the Advanced Men’s class displayed considerable native talent and well-honed skill. If I couldn’t identify with any certainty a future danseur noble among them, I was infinitely touched by one young man in Le Tombeau de Couperin. Perhaps the least proficient in skills of his seven comrades in the piece, all repeating and refracting the same steps, he possesses infinite adolescent grace. He’s still only half way to a grown man’s body, with its expanded chest and steady confidence in its bearing and gestures. He’s at that stage when, the moment a fellow has acquired some command of his rapidly lengthening body, he finds he’s grown another inch—in his sleep, surely—and things have once again fallen apart, with any single move likely to prove unreliable. Raymond Radiguet (Le Diable au corps) and Alain-Fournier (Le Grand Meaulnes) have written eloquently about young men in this phase of their development. Perhaps never again in their lives will they be so vulnerable and so beautiful. The perilous beauty of adolescence is evident everywhere at Workshop, all the more vivid because of the young performers’ unswerving dedication to the standards of mature professional artistry.

Note: Radiguet’s Le Diable au corps (1923) is available in English translation as Devil in the Flesh. In 1946 it was made into a film named for the book, directed by Claude Autant-Lara and starring Gérard Philipe and Micheline Presle. Alain-Fournier’s Le Grand Meaulnes (1913) is available in one English translation under its original French title and in another as The Wanderer. A key incident in the book served as the premise for Andrée Howard’s La Fête Étrange, choreographed in 1940 for the London Ballet.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Kaitlyn Gilliland (standing) and Rachel Piskin in George Balanchine’s Serenade

Serenade choreography by George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

TWO FOR THE SHOW

Mark Morris Dance Group / BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Brooklyn, NY / June 8-12, 2004

The problem with the two new-to-New-York dances Mark Morris paired for his company’s recent run at BAM lies mainly in their juxtaposition. Violet Cavern (being given its world premiere) and All Fours (in its first local performances) are both dry, brainy, essentially abstract works in which structure dominates. Both bring you to your knees in admiration of Morris’s craftsmanship; neither provides much meaningful emotional experience or a lush good time. Neither comes as a surprise or holds any of the surprises—small astonishments at what can be done with a simple step or the placement of bodies in space—that Morris (Mr. Wit, Mr. Invention) is usually so deft at supplying.

All Fours, set to Bartók’s String Quartet No. 4, provides an almost diagrammatic response to the score’s five movements. In the first and final sections, eight dancers in severe black tailoring dominate, moving, often in unison, with the fierce, dedicated energy of a group whose force lies in its very anonymity. It is a mass, with no leaders, no individual temperaments. The three movements at the center feature two pairs of figures in white or light gray ramshackle exercise togs. First we have a pair of men (Craig Biesecker and Bradon McDonald), then the same men plus a pair of women (Marjorie Folkman and Julie Worden), last the two women alone. Though they project no decided personalities, we see them intimately—because of their small number? because of their vulnerable look in their pale clothes? because, while the dark figures moved with an almost compulsive ferocity, their actions seem more passive?

The spectator’s mind inevitably makes stories, if only fugitive ones, out of non-narrative dances—partly from hints planted by the choreographer, partly from a need to “interpret” so as to “understand.” Granted, this is a failure on the spectator’s part, this desire to know, to define, to pin down in ways more appropriate to literature than to dancing, yet it goes on all the time. In this case, I saw the “dark” ensemble and the “light” individuals as the public and private aspects, respectively, of the same group. And I saw the group as a cult, in thrall to a demonic possession, like the societies created by Paul Taylor in Speaking in Tongues and The Word. Out in the lobby at intermission I met colleagues and dance fans who had other stories entirely.

Here’s what led me to my interpretation: The dark figures’ unison aspect; the abrupt, angular, driven nature of their actions; the seemingly compulsive repetition of their gestures, some of them without emotional freight, like a hand thrust forward with the thumb up in hitchhiking mode, others laden with significance such as arms flung heavenward, hands clasped, toward a cast-back head, in the manner of passionately prayerful congregants in a Pentecostal church. (Martha Graham made much of this last in her choreography for the Preacher and his acolytes in Appalachian Spring.) Further: The light figures’ brain-washed demeanor, or at least their look of being subject to influences beyond their control or even full comprehension; their being carried away at intervals like helpless puppets by members of the dark tribe; their repeatedly facing each other and putting a hand to their partner’s lips, the signal serving as a reminder that some terrible secret must not be revealed. (The fact that both the dark and the light groups use many of the key gestures in the piece made me understand them as part of the same community.) And then: Nicole Pearce’s lighting, which keeps the stage ominously dark only to have it flare suddenly, at unpredictable intervals, into hellfire red or a bleak dawn. Others, looking at All Fours, may interpret this evidence differently or, still more likely, see or remember different evidence.

Morris, a choreographer as serious about music as Balanchine was, doesn’t usually work with commissioned scores (which may turn out to be duds), but he made an exception with Violet Cavern. It’s accompanied by about three-quarters of an hour’s worth of partially improvisatory music from The Bad Plus and was played by the group (Ethan Iverson, piano; Reid Anderson, bass; David King, percussion) at the BAM showings. Iverson served as musical director for the Mark Morris Dance Group from 1998 to 2002, which may explain some of Morris’s trust, and The Bad Plus has swiftly made a name for itself in the contemporary music world for its smooth combination of jazz with other forms—rock, pop, heavy metal. I am not knowledgeable in this area, but to me the score seemed insufficiently complex, repetitive, and far too long. Not surprisingly, I felt the same way about the choreography.

The activity is placed in a floating world. The curtained panels that conventionally form the wings at either side of the stage (the place into which dancers ordinarily vanish from view) have been removed. The official dancing ground is delineated by shiny flooring. When the dancers leave it, they quit “dancing” and just walk or run through the remaining indeterminate space, reconstituted as pedestrians, ordinary folk. In modest black box theaters, which have no wings, this state of affairs always prevails, and it has become a popular ploy even on opera house stages. Still, it provides some fascinating sights and a useful prod to re-think what “dancing” means. If you ask me, it’s whatever the choreographer puts in front of your eyes.

Stephen Hendee, the set designer, has been less fortunate with his decoration of the central space. He’s created a crowd of small translucent rectangles crisscrossed with spiderwebbing that hang over the dancers’ heads like clouds that have gotten stuck in an aerial traffic jam. For variety’s sake, colored light is projected onto them at intervals. You guessed it; violet’s first.

Actually the violet cavern idea suits the first half of the piece, which evokes down-and-outers—denizens, perhaps, of today’s or yesteryear’s clubs—who’ve succumbed to drugs, hopelessness, and unfeeling states in which they can see a companion disintegrating, stare at him or her, and drift off or away. There may also be a reference here to the demoralized state of the populace induced by the events of September 11 and their never-ending repercussions.

Ever the master of formal devices, Morris doesn’t slack off here. Many a design or phrase is repeated in exquisitely calibrated variations. The suggestion of life’s being merely a passing parade comes from the pervasive use of bodies facing front while traveling horizontally cross-stage, and in the use of motifs that at their first occurrence look like dramatic events and then, with repetition, prove to be something that can occur again and again, to anyone and everyone. Only one image is striking, but it is unforgettable: Two bodies lie supine, parallel to each other, pushing themselves along the floor, legs bent, with the soles of their feet, progressing with some difficulty, head first. Each extends an arm to a standing figure who grasps it and walks slowly along facing the sliding bodies as if they were dogs and s/he their walker. The connection with photos from Abu Ghraib may be coincidental, but it gives the image a horrifying resonance.

I found the dark sections of Violet Cavern, which account for at least two-thirds of the piece, monotonous. Inventories of the incapacitated, depicting the apathy of the damned, they’re unrelieved by sufficient choreographic or musical inspiration. But it’s the last segment I really object to. In it, the mood inexplicably lightens and, before you know it, everyone is launched into hallelujah activities—leaps with a ravenous appetite, arms flung skyward, dervish whirling at high speed, and so on. This ecstasy without evident cause, which gave me grave reservations about V, the Schumann piece that was Morris’s big 2001 hit, surfaces again and has the audience, excitement built to fever pitch, cheering. In L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, widely considered Morris’s finest work, the exultation of the finale is clearly earned; in V, I would have to agree with Morris if he claimed “The music made me”; here, in Violet Cavern, the resurrection of joy seems arbitrary. On opening night I gauged the audience’s response to the piece as a “maybe”; two nights later the crowd was on its feet, pelting the stage with accolades.

Much was made in the press about Morris’s use of live music in these performances. Much, indeed, should be made in these economically stricken times when dancing has been forced to pretend it is expendable. The truth is that live music is nearly as essential to theatrical dancing as live bodies.

Photo credit: Stephanie Berger: Michelle Yard, Craig Biesecker, Julie Worden, and Amber Darragh in Mark Morris’s Violet Cavern

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

BALLET GALORE: WEEK #6

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 27, 2004

American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / May 10 – July 3, 2004

NEW YORK CITY BALLET: A PAIR OF NEW WORKS FROM PETER MARTINS

I. EROS PIANO

The subtler and more engaging of the two new works by the New York City Ballet’s artistic director, Peter Martins, the trio Eros Piano is set to John Adams’s delicate and complex music of the same name. A flood of luminous color greets the eye as the piece opens. Mark Stanley has suffused the vast bare stage with a glowing turquoise light that suggests an underwater universe. First one woman (Ashley Laracey) picks her way on pointe along a lateral path so far upstage she reads as a shadow, a figure there and yet (do I wake or dream?) not there. Just as she vanishes from view, Nikolaj Hübbe, a substantial figure bathed in a golden glow, traces a parallel path downstage. Then he’s gone and a second fragile figure (Alexandra Ansanelli) appears, she too traveling laterally, so that we seem to be witnessing a panorama-in-time, with the women figments of our imagination and of the man’s as well. To add to the illusion, Holly Hynes has dressed the women in aquamarine unitards, one a paler shade, the other more intense. Hübbe is sheathed in a blue-green tint so faint it looks like ice.

Eventually the three get together, the man first with one woman, then, after she drifts away from him, the other, and finally—this has a wonderful theatrical-shock effect—with both. As a fellow might expect, partnering mermaids, the women’s bodies behave as if they’re infinitely malleable. These circumstances give Martins a perfect opportunity to explore one of his prime areas of curiosity and expertise, convoluted partnering. If he has used it with excessive ingenuity elsewhere, in this instance it is appropriate and lovely. Hübbe manipulates the acquiescent women into all sorts of baroque shapes, wrapped around him like clinging seaweed or poised on the ground as if resting for a moment on the floor of the sea until a passing wave escorts them back to the surface.

Hübbe and Martins both being Danish-born, trained in the school of the Royal Danish Ballet and principals in its company before leaving home for Balanchineland, I couldn’t help thinking, as I watched Eros Piano, of Bournonville’s Napoli, widely considered Denmark’s “national ballet.” In the Blue Grotto scene that constitutes most of its second act, the appealingly plebian hero, Gennaro, enters the dangerous enchanted underwater realm in the hope of rescuing his beloved fiancée, Teresina, lost to the waters when their little boat capsized in a storm. Alas, the demon running the place is busy transforming her into a naiad. Initiated into the sisterhood of water nymphs that he holds in thrall, Teresina will be doomed to lure splendid young men away from real life and its responsibilities into a realm of ceaseless but monotonous pleasure. The key connection between Napoli’s Blue Grotto passage and the situation Martins sets up in Eros Piano is the fact that Gennaro can’t recognize Teresa in her replica-naiad state—she might be any one of those alluring girls gliding around him—nor she (in her mesmerized state) him.

Nineteenth- and 21st-century ballet being obedient to different rules, Napoli ends happily, with Gennaro and his Teresina, having triumphed over seductive evil, reunited in sunlit terra firma reality, whereas Hübbe is finally abandoned by both women—true to their nature (or to the nature of postmodern relationships), they just float away. As the curtain cuts him off from our sympathy, he stands alone, bereft of companionship or enlightenment as to his plight.

Even apart from its chamber-scale cast, Eros Piano is a small piece, unpretentious in its ambitions, focused on filigreed detail. It might be still more absorbing in a theater of more modest proportions. I would like to see it again. Meanwhile I wonder what connection, if any, exists between this piece and Martins’s Chichester Psalms, with which it’s paired on the current season’s programs. Does it lie in a coupling of opposites—Eros and Agape, profane and sacred love?

II. CHICHESTER PSALMS

Leonard Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms—an arrangement, for orchestra, chorus, and boy soprano, of familiar passages from the Old Testament—can be understood as urging, in appreciation of life, the wisdom and reconciliation that will quell factional strife and bring about a holy state of peace. Perhaps Martins decided to stage this score because of the turmoil rife in the world today. Both casts for his setting, named for the music, are led by a fair-complexioned woman and a dark-skinned man. (Carla Körbes and Amar Ramasar did the first performance; Dena Abergal and Henry Seth have also been cast.) The pair act as guides in the cause of calming internecine warfare through a realization that people are more alike than they are different. Ramasar, a gentle, deeply expressive dancer, is the very image of compassion.

The ballet’s opening image, a formal tableau of mixed chorus and dancers ranged in a wide tiered arc, announces the solemnity of the piece. The performers’ black and white costumes (by Catherine Barinas) refer to choir robes and ancient Middle Eastern dress. The female dancers’ white gowns lean toward the Grecian mode, which makes their pointe shoes look incongruous (and suggests that the ballet vocabulary is not the perfect language for the task at hand). The male dancers’ costumes, picturesque swirls of black, owe something to Martha Graham (whose own vocabulary is usefully raided to add a bit of force and expression to the proceedings).

Apart from the two principals, the dancers move in chorus. The most dramatic section has the men paired off in combat, with the women, midway, running lyrically through their midst to quiet the conflict—agents of succor, advocates of harmony. The principals, who seem to be loving partners with regal dignity, simply lead their tribe toward its quiet epiphany.

Overall, the choreography is more like an illustration of principles than an enactment of them. It is also curiously deficient in force and invention. Modern dance choreographers and ballet choreographers with modernist leanings have done more effective work in the choral mode. To name a few: Doris Humphrey, in the architecturally driven New Dance; Martha Graham, in Primitive Mysteries, where the ensemble, with its inexorable tread, becomes the chief character; Bronislava Nijinska, in Les Noces, which vigorously embodies the force of community evident in Stravinsky’s score. Martins’s effort, essentially pallid and banal—the ensemble linking hands to promenade in a snaking chain, and so on—allows your attention to wander to the disagreeable question of whether or not Bernstein’s music wants, or even really permits, a visual complement. I suspect that it doesn’t.

The score, conducted by Andrea Quinn, was persuasively sung by the Juilliard Choral Union (directed by Judith Clurman) and the thirteen-year-old James Danner, who duly produced some of those unearthly tones that reinforce the beliefs of the faithful and give religious skeptics second thoughts.

AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: GILLIAN MURPHY

Gillian Murphy, who dazzled this past week in Ballet Imperial, is a ballerina in every fiber of her being. Her own dancing is bold, confident, and magisterial; what’s more, she looks as if she’s the animating force behind the whole ensemble. Self-contained, immune to flourishes of ego, she simply takes charge of everything that’s happening on stage, making the entire ballet cohere.

By a slight re-angling of her body in partnered adagio, she shifts from one potent image to another. Here she’s a princess in a tragedy of love, the next moment a bird poised for flight—an icon of freedom. She’s too singular and formidable a physical personality to qualify as a natural actress—she’ll have to approach drama-dependent roles obliquely, as she did with Hagar in Tudor’s Pillar of Fire. Perhaps her innate ability to create telling images—physical metaphors, as it were—will prove sufficiently theatrical in itself.

Tall and large-boned, with a striking face (often compared to Bette Davis’s) and phenomenally adept technique, she seems, sui generis, powerful and regal. The next time company and choreographer find themselves casting about for a subject as they set out to spend zillions concocting a latter-day multi-act, lavishly decorated story ballet—these items may not advance the cause of dance but they often sell tickets—they’d do well to think of Murphy as Queen Elizabeth I (also an imperious redhead) or Catherine the Great.

Photo credit: Marty Sohl: Gillian Murphy and Carlos Molina in the American Ballet Theatre production of George Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial

© 2004 Tobi Tobias