American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / May 10 – July 3, 2004

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 29, 2004

AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE: GALA

American Ballet Theatre’s opening night gala was a model of good taste. The company’s well-heeled supporters, definitely part of the show as they milled about the lobby and curving staircases of the Metropolitan Opera House, were exquisitely dressed. Immaculately groomed men in the black and white uniform their role requires provided a complementary background for their gaudier ladies. The women’s ensembles—a preponderance of them cut Botticelli-style from delicate fabrics in springtime hues—constituted a delectable fashion parade (and were duly ogled as such by the more pedestrian crowd peering over the balcony rails). The onstage entertainment was equally graceful, the many entries on evening’s program scrupulously chosen and balanced. Amidst all this refinement, I must admit, I almost missed the raw vulgarity—on both sides of the footlights—of the Bad Old Days: the garish gowns-from-hell, the acrobatic variations on the theme of the 32 fouettés.

If the program was, as my date remarked, “all arias, no recitative,” the smorgasbord (to shift metaphors) approach was appropriate to the occasion—providing a taste of things, no deep immersion—and consciously reflected ABT’s sense of its present identity.

Represented first and foremost was the idea of ABT as a custodian of what can loosely be called “the heritage”—classics from the nineteenth century and latter-day works explicitly declaring their adherence to that tradition. The performance opened with the first movement of George Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial, and it’s significant that ABT’s production of the piece harks back to the old version, which evoked the glories of tsarist Russia in its costumes and décor, though the New York City Ballet has itself moved on to a streamlined scenic investiture and has renamed the ballet after its music, Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2. Representing the actual nineteenth-century part of the heritage category were the extended unison adagio for the female ensemble from the Kingdom of the Shades scene of La Bayadère and chunks of both classical and “Hungarian” passages from the company’s new production of Raymonda, which is about to have its official American premiere.

All three excerpts, and they were substantial ones, were performed with great care, reflecting admirable commitment and hard work from the dancers and their coaches. For the most part, though, the material didn’t quite take wing. The company seems caught between the deliberate Russian style with its sculptural and soulful beauties, and American style, with its speed, sharpness, and verve. Despite its good intentions—and, indeed, its frequent beauties—the dancing seemed deficient in breath, musicality, and, above all, spontaneity. Only the Bolshoi-bred Nina Ananiashvili, in Raymonda, looked fully at ease with her assignment, confidently opting for Russian sublimity as if the alternatives were irrelevant to her identity as a ballerina.

Two pièces d’occasion proved engaging enough to be repeated on other occasions. Carmen Fantasy featured the onstage performance of the violin virtuosa Sarah Chang, gowned in red sequins, playing Pablo de Sarasate’s score with fiendish precision and wild feeling. Kirk Peterson’s choreography is a distillation of the Carmen theme—an elixir of tawdry glamour, bad blood between the lovers, voyeurs and provocateurs in the form of cigarette girls, and so on. Miraculously Peterson keeps his material from lapsing into Backstreet Spanish clichés; instead, he makes the dancing swift, vivacious, technically and atmospherically out for blood—and astonishingly contemporary.

To honor that seemingly ageless man of the ballet theater, the soon to turn 90 Frederic Franklin—still a force in coaching and in retrieving worthy old ballets from limbo, as well as a sometime performer—ABT’s artistic director Kevin McKenzie devised the punning A Sweet for Freddie. The affectionate bagatelle invokes Franklin’s long identification with Coppélia, which ABT will present later in the season. (Once upon a time, Franklin played Franz to Alexandra Danilova’s memorable Swanilda for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo; in later years he moved on to a finely etched portrayal of Dr. Coppélius and to stage the ballet as well.)

McKenzie generously gives the debonair Franklin two Swanildas to waltz with (Amanda McKerrow and Ashley Tuttle, the most gentle-tempered of ABT’s ballerinas), and then provides two more, each eventually furnished with a slightly dumb, slightly loutish Franz. From time to time the multiple Swanildas lapse into Coppélia’s mechanical-doll state and have to be rescued from such restrictions on their mobility and élan through a bit of Freddie’s trenchant yet graceful mime. At the end, Franklin gets to leave with all four beauties on his arm, their swains registering bafflement as to how the dude brought it off.

The indelible moment of the piece comes right up top, where Franklin, dapper in evening dress, enters and strolls briskly down the diagonal of the Met’s enormous stage with the fluency of a well-exercised fellow one quarter his age. He doesn’t look like he’s dancing, and he’s immune to the affectations of performing. He simply looks like he’s walking—on a clear day in mild weather, certain as any instinctively sanguine man can be that the future is about to offer him unexpected delights.

In the program’s gimmick department—an element absolutely essential to galas—we got David Parson’s Caught, which uses strobe lighting to freeze-frame its solo performer (here Angel Corella) in a swift succession of suspended-in-air positions, and Christian’s Spuck’s Le Grand Pas de Deux, a spoof of the genre dependent on junior high school humor, emphatically performed by Irina Dvorovenko and Maxim Beloserkovsky.

True to its mission, the evening showcased the company’s extraordinary constellation of stars—among them, in addition to those noted above, Alessandra Ferri and Julio Bocca, gorgeously lascivious in the bedroom pas de deux from Kenneth Macmillan’s Manon; Gillian Murphy and Ethan Stiefel, mistaking the tone of Balanchine’s Tarantella, but dazzling nevertheless; and Jose Manuel Carreño as both take-your-breath-away technician and the guy everyone wants to go home with, in his solo from the bravura Diana and Acteon pas de deux. It also managed, with the Kingdom of the Shades passage, to pay due homage to its ensemble, from which the next generation of stars will spring.

NEW YORK CITY BALLET: CHRISTOPHER WHEELDON’S SHAMBARDS

“Is this a word we’re supposed to know?” a fellow was asking in the intermission that followed Shambards, Christopher Wheeldon’s latest work for the New York City Ballet. Well, no, and the audience would have benefited from the elucidation that was available in the press kit but not in the house program. The ballet’s score was commissioned from the Scottish composer James MacMillan, who titled its middle section “Shambards” after an epithet in an Edwin Muir poem that mourns the destruction of the national ethos, calling Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott “sham bards of a sham nation.”

Wheeldon’s ballet, which is semi-abstract, seems only vaguely related to this issue. It prioritizes patterning, with an ensemble that moves in intricate sharply-etched configurations. The corps work is infused with references to tightly controlled shape—in the parades of Scottish bagpipers, Highland dancing, and the intricate formalities of Celtic design. All this essentially decorative business is carried out cleverly and meticulously in the ballet’s three movements. The result, though, feels too neat, too clean, too self-conscious. Its lack of organic impulse leaves it devoid of sweep and surprise.

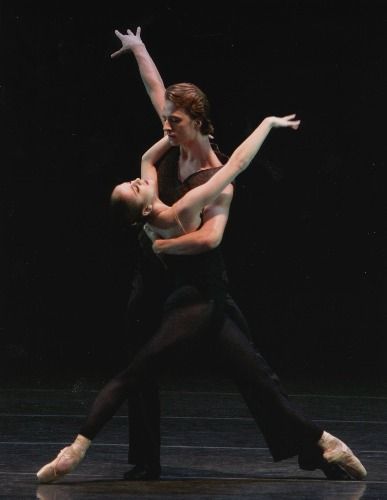

Punctiliously positioned against the corps work are some baffling exercises for the soloists. In the opening section, called “The Beginning,” Carla Körbes and Ask la Cour seem to be merely central figures in the handsome shifting patterns that inexorably take possession of the stage. I read this couple as primogenitors of the race, who emerge from the tribe and are, perhaps, ritually sacrificed at its hands.

“The Middle” focuses on a couple (Miranda Weese and Jock Soto) with more contemporary romantic tsuris. We see disagreement, along with hints that it’s rooted in chronic, low-lying anger. We see sorrow, and then rapprochement; shards of a waltz tune surface in the music. Suddenly the man flings his partner to the floor, drags her around by one arm, then holds her limp body in front of him, as if bearing a corpse. Observers more concerned with the evolution of academic ballet technique than the plight of battered women will explain that Wheeldon is experimenting productively here with the traditional adagio form, “advancing” it so that the lady is free to relinquish her right to verticality for a horizontal position on the ground, her gentleman friend lending a hand as he looms above her.

“The End” adds two diminutive pairs of virtuosi (Ashley Bouder and Daniel Ulbricht; Megan Fairchild and Joaquin de Luz) to the ensemble for some immaculately structured dancing in kaleidoscopic patterns. This material escalates from folkish exuberance to the edge of danger, at which point Weese and Soto return to re-enact their catastrophic encounter. Now, instead of presenting her body straight on to the spectators with the air of a horrified penitent, he drags it sullenly into the wings. The ensemble, which had arranged itself like an allée of trees to frame the terrible scene, simply melts away in the descending darkness, as if it had been destroyed by what it witnessed. If you work hard, you can make the onstage scenario fit the Muir.

Holly Hynes has created stunningly simple costumes for Shambards in a palette of browns, grays, russet, claret, and ebony. A set of skirts that look like kilts with some bounce to them is nothing less than ingenious. Mark Stanley has worked complementary wonders with the lighting, rendering the stage dense with brooding and threat.

The very best thing about Shambards is that it provides a featured role for Körbes, a nascent ballerina worthy of far more significant assignments than she’s currently getting. Indeed, she’s the only one of the company’s young women on the rise who would be perfect in both female roles in the NYCB’s most rewarding excursion to the Highlands, Balanchine’s Scotch Symphony.

HERE ON A VISIT:

I. NYCB: LORNA FEIJÓO & GONZALO GARCIA

Guest dancers from companies with a “Balanchine connection”—through their artistic directors, past or present, and their repertory—are adding spice to the NYCB’s already eventful season. To date, the most gratifying visitors have been Lorna Feijóo (currently with Boston Ballet) and Gonzalo Garcia (from San Francisco Ballet). Although neither of them seems destined by training to be an exemplar of the Balanchine style, they revivified the exhilarating Ballo della Regina.

Feijóo, a product of Havana’s National Ballet School and a former principal with Ballet Nacional de Cuba, displays the virtues of that tradition—killer technique coupled with fervent feeling. Think Alicia Alonso. To my mind (I saw her work with the Cuban company), Feijóo is essentially a Romantic dancer, and she didn’t, indeed, embody the qualities of fresh-air fleetness and crispness on which the Ballo role, originated by Merrill Ashley, was built. Yet her performance—full of exuberance grace, eager to please yet not show-offy—was both delightful and persuasive.

Gonzalo Garcia, who is only 24, trained in his birthplace, Spain, before emigrating to San Francisco. Along the way, he seems to have won prizes at every ballet-competition in sight: youngest to take the gold at the Prix de Lausanne, and so on. In Ballo, he looked like a boy dancing not for the gold but for the hell of it, out of sheer animal spirits. Arms loose and free, he seemed to gambol, now over the earth, like Pan, and just as easily, like Ariel, in the air. He brought off the virtuoso feats the choreography requires without emphasizing them, incorporating them instead into the coursing flow of the movement.

Beyond their command of the formidable technique Ballo demands, both dancers displayed an ardent involvement with the feelings that lie latent in the choreography as well as an intense communication with each other. (Risky as it is to generalize, passion, too often absent from classical dancers who are American- born and –bred, seems to be the birthright of those whose mother tongue is Spanish. It must be something in the culture.) Wrongful though kidnapping may be, I’ll bet New York balletomanes have been speculating on the possibility of Feijóo’s and, especially, Garcia’s remaining with the hosts of their recent brief encounter.

II. ABT: ROBERTA MARQUEZ

Remarkable dancers from Elsewhere have long been a staple of the star-conscious American Ballet Theatre. The Kirov’s Natalia Makarova was just one such acquisition, and it was in her staging of La Bayadère that the Brazilian-born and –trained Roberta Marquez has been introduced to stateside fans, first in DC, now in New York.

The 26-year-old Marquez is a principal with the Municipal Theatre Ballet in Rio de Janiero and a guest artist with England’s Royal Ballet. She’s is an extremely petite woman, small and delicate enough to make her partner, the concisely built Ethan Stiefel, look bulking and towering—way macho. If she is not a great artist, she is clearly a star. The earmarks? Impressive technique with the daring to match, sensational projection, and, I suspect, the kind of confidence and desire usually reserved for people performing acts that are going to result in military medals or canonization.

She may be small, but she dances huge. In Bayadère, from the moment her veil is lifted to reveal her piquant face and a body that is tremulous even in stillness, she’s eager to reveal Nikiya’s single-minded passion for a lover whose heroism is nowhere up to hers, the hurt-child pathos proper to the situation, and (half-hidden, of course) the character’s yen for immolation. (Nikiya’s finest hour, Bayadère watchers know, comes after her death).

As the living and loving, rivaled and wronged Nikiya, Marquez is persuasive in her earnestness, admirable in her commitment to the melodrama of the story. Once Nikiya is a ghost, Marquez duly makes her as remote and disembodied as a spirit should be, all the while attempting to convey the tenderness and longing Nikiya still feels for her sorry lover. Somewhere along the way, though, Marquez loses her grip on her viewers’ rapt fascination and belief—because her conspicuous physical prowess and her apt characterization lack the support of that indefinable yet immediately recognizable element we call “soul.”

In many ways the model for Marquez is, in her own generation, Alina Cojocaru, and, before that, Gelsey Kirkland. Marquez is similar to them physically, arguably their near-equal technically, but she lacks their incandescent spirit. Perhaps it is lying dormant in her and will surface with time. I hope so, but I’m not counting on it, since the quality is one that, in ordinary life as well as artistic life, is usually evident by adolescence. Such a blessing is impossible to conceal.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Carla Körbes and Ask la Cour, in Christopher Wheeldon’s Shambards

© 2004 Tobi Tobias