New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 29, 2004

Following are comments on the highlights of the second week in the New York City Ballet’s spring season, Part II of the company’s Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration.

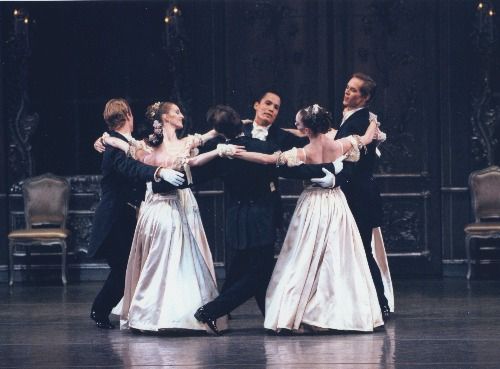

LIEBESLIEDER WALZER

Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer, created in 1960 and given three luminous performances in the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine 100 centennial celebration, lasts for about an hour. It is so lovely and so infinitely inventive, you feel you could watch it forever.

A quartet of singers and a pair of pianists perform onstage for four couples who dance, the conceit being that they are all participating in a musical evening at home, a familiar pastime among the upper classes of nineteenth-century Europe. Their music consists of two Brahms song cycles whose titles translate as Love Song Waltzes and New Love Song Waltzes. Their setting, designed by David Mitchell and said to be inspired by Munich’s Amalienburg Palace, is an elegant interior with filigreed paneling and furnishings to suit, the space gleaming bronze and pearly gray, as if softly lit by the candles in the wall sconces and the crowning chandelier. Dancers and singers wear similar period evening dress. Karinska’s now legendary gowns for the women—cut with panache from luxurious low-gloss fabric, each in a different, barely perceptible, pale shade of off-white—are beautiful in stasis and ravishing in motion.

The choreography for the first half of Liebeslieder is an extension, along balletic lines, of social dancing, specifically the waltz, but it is no more like decorous social dancing than are the duets of Fred and Ginger. It constitutes a lexicon of movement, timing, impulse, and suggested emotion—all kept within the confines of waltz tempo and the situation that has been proposed. There are lifts, for example, but they skim the ground, never vault into the air; if on occasion they soar a little higher, the woman’s partner still holds her vertical, as if she had just floated some inches upward from her erect dancing position. All the while, the tours de force of timing are coupled with mercurial shifts in mood. The tact, intelligence, and sheer theatrical genius with which everything is deployed seems nothing short of miraculous.

It’s important to note, I think, that Liebeslieder’s four couples form a community of familiar friends. They gather regularly, one is lead to assume, in each other’s exquisitely appointed homes for an evening of music and dancing. They’re more than acquaintances surely, and perhaps, on occasion or merely through the mind’s fugitive caprices, cross-couple intimates (though ultimately faithful to their partners). From time to time, two, three, or all four couples dance together, and this periodic deflection from the duet form that dominates the dance is perfectly calibrated, and frequently astonishing. Besides providing variety, the larger interaction roots the proceedings in the idea of social intercourse, proposing it not merely an amenity but as an element crucial to a life fully lived and fully felt.

When the first songbook comes to a close, the dancers throw open the room’s three double doors and escape into the moonlit gardens that one imagines lie beyond—for a breath of fresh air, or perhaps to exchange sentiments that belong to two people alone. Some moments later, the artificial candles extinguished, the lighting given a blue cast that heightens the impression of night and mystery, the dancers reappear. The women who trod the floor lightly enough in their heeled ballroom slippers and voluminous ground-brushing skirts are now clad in pointe shoes and gauzy tutus with blossom- and dewdrop-studded ribbons lying just visible under the top layers of mist-tinted tulle. The flesh-and-blood inhabitants of the gracious room have been transformed into the creatures of their own dreams, launched into a space of uncertain boundaries.

In this part of the ballet, each couple has more time alone, unwatched by the others, because the illusion of a social occasion has been shed, and because the dancing has shifted to a fantasy world, a venue that—apart, of course, from folies à deux—is essentially private. The choreography for the latter half of Liebeslieder is, as you’d expect, more conventionally balletic than it was in the first—swifter, more daring, more intense—but it retains vestiges of social dance that link it to all that has gone before, and, as before, it is suffused with heady emotion. Eventually, pair by pair, the dancers flee even this less circumscribed space, and the stage is abandoned to the musicians.

The lyrics of the final song come from Goethe: “Now, you Muses, enough! In vain you strive to describe how misery and happiness alternate in a loving breast. You cannot heal the wounds that Amor has caused, but solace can come only from you, Kindly Ones.” Slowly, again in couples, the dancers return, once more in mufti, to sit or stand meditatively, listening. When the music concludes, they gently applaud the musicians with their immaculately gloved hands as the curtain falls.

Liebeslieder has no narrative content, unless you count the precipitous shift from reality to ecstasy that occurs between its two parts as a specific event in time. (I don’t; I think it’s the kind of leap lyric poetry makes, independent of plot.) Neither is the choreography tethered to the lyrics of the songs. Its subject, apart from the music itself (as the choreographer might have argued), is, I would say, the many faces of love. If there is any aspect of civilized love that Balanchine hasn’t treated here, I can’t imagine what it might be. Charged with moods that fluctuate like spring weather, sometimes within a single brief duet, the ballet reveals romance to be, by turns, tender, joyous, pensive, flirtatious, wistful, tempestuous, angry and conciliatory almost in a single breath, occasionally near-tragic. Love in Liebeslieder is imbued with nostalgia, existing as much in perfumed memory as in the ardent—often impetuous—declarations of a present moment. It is shadowed here and there by intimations of death, as if affairs of the heart could have no meaning without reference to the inevitable event that would annihilate them. If you’re susceptible, the ballet stirs all your hidden feelings about love, perhaps even a few you’ve been keeping secret from yourself.

Innumerable leitmotifs weave through the ballet, surfacing and ebbing, according to the “climate” of a particular performance and the individual viewer’s focus of attention. Over the years, observers have detected a theme they refer to as “the girl who is going to die.” Her initial duet with her partner is happy and bounding, almost like a polka. But in their second she seems to be attempting to tell her lover some terrible secret, one that he already knows in his heart but can’t bear to hear. He shields his face with the back of his white-gloved hand; her lips, ready, finally, to whisper the fateful words, nearly brush his palm. And all the while they go on dancing; none of the lightly etched gestures and poses of this little drama interrupt or override the momentum of their movement to the music. In a third duet, though, she swoons backward in his arms, hand to brow, the image of a person overtaken by faintness or fever. Regaining her footing, she moves away from her partner, as if illness likely to prove mortal had already isolated her from the consolation of his embrace. After a moment, they come together once more, but when she falters in his arms a second time, he lifts her extended body horizontally so that, for a brief but indelible moment, she is already a corpse. One of her arms is folded so that her hand rests on her breast; the lavish folds of her long pale skirt streaming away from her body resemble a winding sheet that has not yet been pinned into place. In Part II the relationship of the pair has almost no dramatic implications, but as the role is danced today, the young woman has become cousin to The Sleeping Beauty’s Aurora revealed to Prince Désiré as a vision and Giselle’s doomed heroine returned to Earth as a spirit—in other words, impalpable.

Grace governs this ballet. The dancing, with the waltz as its heartbeat, is graceful. The behavior of the inhabitants of that exquisite room is as graceful in its sense of decorum’s parameters as it is in its gestures. And the dancing figures, first experiencing a gamut of the subtle emotions that belong the real life of people with high sensibility, then suddenly projected into the wilder world of their imagination and yet safely returned home, are surely in a state of grace.

At the premiere of Liebeslieder, in 1960, they took the house lights down to half for the extended pause between the two sections. I remember sitting in the hushed twilight and thinking, This is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen. I’ve had little cause to change my mind since, despite casts subsequent to the original one that were not quite as wonderful. To my mind, the company’s current rendition is the finest—the most coherent as an entity, and the most moving—since the ballet’s first season.

The original dancers were: Diana Adams and Bill Carter; Melissa Hayden and Jonathan Watts; Jillana and Conrad Ludlow; Violette Verdy and Nicholas Magallanes. The current dancers are: Darci Kistler (in the Adams role) and Philip Neal; Kyra Nichols (Verdy) and Jock Soto; Miranda Weese (Jillana) and Jared Angle; Wendy Whelan (Hayden) and Nikolaj Hübbe.

Even today Liebeslieder remains charged with the dancing personae of the artists on whom it was created. Yet it is magically potent for viewers ignorant of past. Just this week, a burgeoning ballet fan told me, “I’ve never seen anything staged with such a combination of fragrance and philosophical depth.”

EPISODES

Because of the way the NYCB has organized the second half of its Balanchine 100 centennial celebration–with “Tribute” evenings that cluster ballets to scores from a particular nation—a surfeit of lushness prevailed in the first two weeks’ programs, when first Germany then Austria took their turn in the spotlight. Entering the rep at the close of week two, Episodes, to a handful of typically brief, stringent pieces by Webern, was a welcome relief—a dry martini, citrus sorbet.

The current production is stunning. It’s performed on a bare stage against a pearly blue-gray cyclorama and side pieces, their cool simplicity emphasizing the high vault of space stretching over the dancers’ heads. In this empyrean emptiness, clad in severe black practice clothes and moving with impeccable clarity, the dancing figures conjure up images of graphs, musical scores, Asian calligraphy. At the same time, they seem very human, acutely attentive to nuance as they execute their austere, enigmatic rites. It’s startling to realize that, forward-looking as Episodes was when it was made in 1959 and forward-looking as it remains, the choreography might be the skeleton of crystalline passages from Petipa.

Symphony, Opus 21:

The steps seem to fall between the notes, both steps and notes spare and dry, compelling in their simultaneous oddity and logic. Here music and choreography appear to be the related languages of a locale in interstellar space.

Relaxed but remote, the performers’ faces are uninflected by expression. Their bodies, deployed in space and time, do all the talking.

When the dancers need to stop what they’re doing and get to another spot on the stage to begin again, they just quit, without flourishes, and walk casually to where they need to be. This tactic is unheard of in classical ballet.

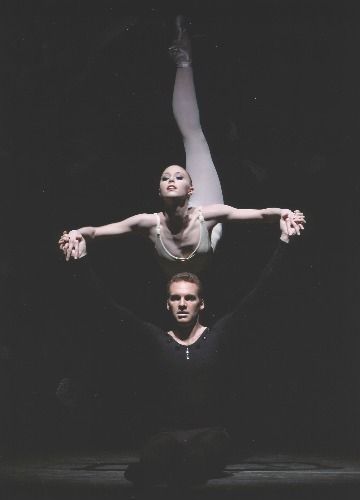

Five Pieces, Opus 10:

A duet for strangers in the night.

The space is so dark it seems borderless. Roving spotlights, beamed from above, pick out the two figures—a man (James Fayette) in black, with only a sprinkling of reflective material at the neckline to increase his visibility, the woman (Teresa Reichlen) sheathed in chalk white. She’s one of the company’s Tall Ones, with legs that go on forever, and uncannily malleable. Awed, curious, and occasionally baffled, the man manipulates her fantastic body, and she cooperates as if being the clay in his hands were her chosen destiny, twisting and twining into seemingly impossible positions. The effect is eerie, sometimes grotesque, occasionally funny. One thinks of Balanchine coming to America—the choreographer led, through the cryptic workings of Fate, to the land of extraordinary female anatomy, and setting to work.

Concerto, Opus 24:

At this point, a ballet with a normal regard for convention would offer its centerpiece—a love pas de deux. This duet is one, of sorts, in a way that’s ironic and illuminating. Pliable as a rubber band, Wendy Whelan exaggerates her loose-jointed, sinuous capabilities, keenly alert to timing and texture. Albert Evans anchors her with his potent theatrical presence. The four women constituting their entourage perform their spider-like maneuvers—all lines and angles, understated, mesmerizing. The weirder the goings-on in this ballet, the more beautiful they are.

Ricercata in six voices from Bach’s “Musical Offering”:

Just when you thought the universe had been reduced to fragments, Webern puts it together again, anatomizing Bach. In the lead, Maria Kowroski and Charles Askegard are angels of coherence. They’re abetted by 14 women who form matrixes that make order visible. Facing the audience straight on, they advance towards it on legs that devour space, or place themselves like markers on an invisible grid, standing erect on their knees. When you notice that this drastic, peculiar image harks back to the opening section of the ballet, you understand that, throughout the piece, Balanchine has been holding the world safely in his hands, rendering it comprehensible despite its elements of chaos, perhaps even relishing those excursions into disorder, like a god at play.

OCCASIONS:

I.

May 1, the New York City Ballet declared its performance—of Balanchine works to the music of German composers—to be Alumni Night. It was the public face of a weekend-long reunion of NYCB dancers, some 200 of them, dating back to the company’s official beginning in 1948. With offhand charm, Peter Martins emceed the onstage presentation of dancers who had originated or inherited principal roles in the ballets about to be danced. The ballets were : Kammermusik No. 2, Liebeslieder Walzer, and Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet. The dancers were: Jacques d’Amboise, Karin von Aroldingen, Gloria Govrin, Melissa Hayden, Jillana, Allegra Kent, Sean Lavery, Sara Leland, Colleen Neary, Adam Lϋders, Mimi Paul, and Suki Schorer.

Then Martins asked the other alums present, seated in the audience, to stand. Of course the rest of us wanted to peer and cheer. And so we did, long and loud. We were looking at nearly six decades’ worth of remarkable people, major and minor talents alike, who had dedicated themselves to one of the great communal artistic enterprises of the twentieth century—the creation and (since a dance lives only in its performance) the ongoing re-creation of Balanchine’s ballets.

It was interesting to identify these notable dancers, featured and ensemble players alike. Folded into the house program was a list of their names, most of which, to veteran fans, evoked images and memories far more vivid than those provided by the entries on the old-acquaintance rosters of our college reunions. It was absorbing as well to contemplate the further unfurling of their careers after they left the stage. Many, of course, have gone on to the logical extensions of a dancing life as artistic directors, choreographers, teachers, stagers, coaches, and members of dance institutions’ production and administrative staffs—often with the NYCB and its affiliate academy, the School of American Ballet. Others have ventured farther afield, into a range of professions that includes writing and photography, medicine and the law. And it was tantalizing, since we knew them in their onstage incarnations primarily as physical presences, to find out how they look now, in body and dress, as “pedestrians.” But no matter how avidly we stared and guessed, curiosity and gossip being fundamental to human nature, I, for one, had to admit that what they offered Balanchine and their audience remains the most unusual and fascinating thing about them. A major part of their being, and the element that united their disparate temperaments, had been, in their performances over all those years, right out there in front of our eyes.

II.

If the New York City Ballet’s Alumni Night paid a personal, suitably low-key homage to Balanchine through the generations of dancers associated with him, a special program on May 5, “Lincoln Center Celebrates Balanchine 100,” was its tell-the-world statement. Before a packed—and exceedingly well dressed—house (the occasion served as the NYCB’s Spring Gala), the 12 resident institutions of Lincoln Center joined forces in an evening of music, dance, film, and talk. It was beamed out, live, onto a Brobdingnagian outdoor T.V. screen on Lincoln Center Plaza (where folding chairs had been set up for spectators undeterred by threats of rain), telecast by PBS into millions of homes with no dress requirements whatsoever, and thus recorded for posterity.

The program was, predictably, star-studded, decorous, and entertaining. If provocative, introspective, or simply thrilling was what you were after, this was not your night. Indeed, it hardly represented Balanchine’s immense achievement, since it relied, for the most part, on segments of ballets guaranteed to please easily, like the gypsy finale of Brahms-Schoenberg Quartet and the grand conclusion of Vienna Waltzes, with its dozens of couples uniformed in sumptuous black and white evening clothes sweeping around magnificently in a mirrored ballroom that doubles their numbers and impact. The most “advanced” work on the program was Concerto Barocco, represented by its sublime adagio, sublimely danced by Maria Kowroski, with James Fayette as her attentive, anonymous cavalier. But the radical choreography with which Balanchine changed the face of classical dancing—in works like Agon, Episodes, Violin Concerto, and Symphony in Three Movements—might never have existed, for all this program revealed about them.

There were some agreeable small and subtle touches, though. Placido Domingo’s rendition of Tchaikovsky’s “None but the Lonely Heart”—purportedly one of Mr. B’s favorite songs—was echoed by the Gershwin song “The Man I Love,” with Alexandra Ansanelli and Nilas Martins dancing the segment Balanchine choreographed to that music in his Who Cares? This entry had Wynton Marsalis playing trumpet onstage, an event that had itself been heralded by the program’s starting with the trumpet duo Fanfare for a New Theater, composed by Stravinsky for the opening, in 1964, of the New York State Theater, built to house Balanchine’s enterprise. And of course there were heavenly, if intermittent, dance moments, such the perfect timing and tone with which Peter Boal and Yvonne Borree concluded a section of Duo Concertant, in which they’re accompanied by an onstage pianist and violinist, turning away from the audience and toward the instrumentalists—just slightly, and with just a suggestion of a bow—as if to indicate that their dancing existed simply to be absorbed back into the music from which it had sprung.

The evening was emceed live by Sarah Jessica Parker, who has no evident Lincoln Center connection, but who rose above her fame to do the job with modesty, freshness, charm, and a wardrobe of three different snazzy evening dresses. On screen, the Broadway choreographer Susan Stroman, associated with the Lincoln Center Theater, told Balanchine stories in a down home style to introduce film and video clips meant, I guess, to reveal the “human” aspect of the choreographer. Balanchine and Stravinsky consuming a pick-up lunch as they worked together. Like that. Situations in which Balanchine was asked to describe what he did and how he did it are patently ludicrous. Does such footage really succeed in domesticating a subject—the achievement of genius—that otherwise leaves us paralyzed with awe?

In truth, though memory-sharing and gala celebrations have their place, there’s no fully adequate way to pay homage to Balanchine. The most useful, and most unendingly difficult, way is to give ongoing vitality to the dances he created by performing them in the style to which, under the choreographer’s own aegis, they were accustomed. The actor Kevin Kline aptly offered these lines, from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, gesturing toward the stage where the dancing happens on the word this: “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.”

Photo credit: Paul Kolnick: (1) George Balanchine’s Liebeslieder Walzer; (2) Teresa Reichlen and James Fayette in Balanchine’s Episodes

Translation of Goethe’s “Nun, ihr Musen, genug”: Emily Ezust

© 2004 Tobi Tobias