American Ballet Theatre / Metropolitan Opera House, NYC / May 10 – July 3, 2004

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / April 27 – June 27, 2004

Dance Theatre of Harlem

AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE

When it comes to George Balanchine’s 100th birthday, the New York City Ballet is, by rights, the chief celebrant, but it is hardly alone. The homage has been national, international, and well-nigh relentless. This past week, NYCB’s nearest neighbor, American Ballet Theatre, joined in officially with its all-Balanchine program: Theme and Variations, Tchaikovsky Pas de Deux, Mozartiana, and Ballet Imperial. The program constituted a cornucopia of choreography, staged with vigor on several different sets of principals, as if ABT wanted to ensure that the largest possible number of its leading dancers shared in the experience, which was surely an instructive one.

The performance I chose—for its overall casting—was given before an audience packed with connoisseurs and offered many beauties and many thrills. For me, its highlights were the production of Theme and Variations and Veronika Part’s dancing in Mozartiana.

Theme, set to the final movement of Tchaikovsky’s Suite No. 3 for Orchestra, was commissioned from Balanchine by ABT in 1947, to showcase the spectacular classical technique of Alicia Alonso and Igor Youskevitch. It remains a challenge even today, with its exacting and inventive choreographic mini-essays on basic elements of the danse d’école (the extension of the foot in tendu, the jump, the turn, the partnered adagio). Understandably, it is most often danced with a concentration on the impeccable execution of its myriad feats, so that, witnessing a successful performance of it, you feel exhilarated but not necessarily moved.

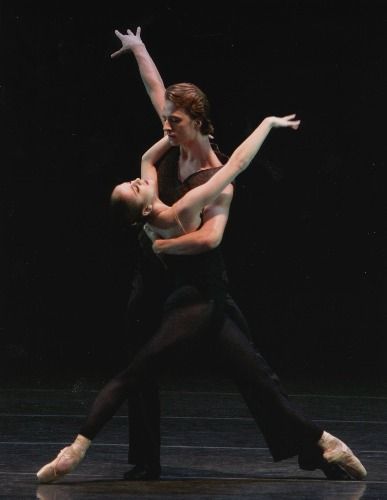

In the current production, marvelously staged by Kirk Peterson, Ashley Tuttle’s presence in the ballerina role changed the emphasis. While Tuttle’s a strong technician, she makes herself memorable through her musicality. Nowhere did she sacrifice precision, but her message was clear: the essential unit of dancing is the phrase, not the step. This understanding provided an alchemy that turned motion into emotion, revitalizing the choreography.

Tuttle’s partner, Angel Corella, was equally admirable, matching her phrasing-first approach and exchanging his familiar heroic-bravura style for luminous decorum. The solo in which he alternates double air turns with double pirouettes was impeccably done, not a bit circusy, yet not textbook-dry either. He offered dancing as close to perfect as we’re likely to get in this life, yet charged with tremendous energy held just in check.

I don’t think it was just the Bengal-rose hue of the principals’ costumes—a throwback to Aurora’s tutu for the Rose Adagio in The Sleeping Beauty—that suggested the Theme couple might be Princess Aurora and Prince Désiré on, say, their tenth wedding anniversary. The cue was embodied in dancing that suggested a still youthful pair, still loving, still trusting in visions, now settled into a fruitful reign over a peaceable kingdom.

The demi-soloists and the small ensemble echoed the behavior of the principals at every moment—in clarity, strength, vivacity, and, above all, musical impulse, making the performance as a whole remarkably alive and human.

The role created on Suzanne Farrell in Mozartiana gave the 26-year-old Veronika Part the best opportunity she’s had to reveal her gifts since she joined ABT nearly two years ago. The infinitely soft and sculptural movement of her upper body, enhanced by her Kirov training, makes for a ravishing port de bras. Her cushioned footfalls have an unusual and satisfying weight. She registers not as “girl” or “spirit,” but as “woman.” Beyond that, her lushness in motion is so innately expressive, you imagine it would be fascinating simply to watch her going through her ritual of daily exercises at the barre.

In the rising generation of ballerinas, Part is the most physically like Farrell—she has a similar opulent physique and her movement has the same voluptuous texture—but Farrell is a hard act to follow, as is Nina Ananiashvili, who, originally coached by Farrell in a Bolshoi Ballet production, now dances the role at ABT, where Mozartiana has been staged by Maria Calegari.

It’s still early days for Part in this strange, beautiful ballet, which demands so much of both body and soul. In the opening Preghiera (Prayer) section she didn’t seem so much steeped in devout communion as acting—unaffectedly, but still acting—a state of holiness, while Farrell so nakedly invested the choreography with her entire being, she made Balanchine’s inventions appear to be a reflection of her own guileless, ardent heart.

Ananiashvili has been able to grasp something of Farrell’s intentions in her performance, whereas Part, at this juncture, can show us only a vastly gifted young dancer operating on some tentative instincts. In this role, she seems only half-realized as a dancer, barely realized as an artist, yet clearly possessing tremendous potential—and this is what’s so touching in the experience of watching her just now. Someone should tell her not to smile.

NEW YORK CITY BALLET: IVESIANA

I wish I understood better why Balanchine’s Ivesiana made such a piercing impression on me when I first saw it with its original cast and why every subsequent encounter with it—I got to see it twice last week—has confirmed its power. Is it Balanchine’s acute response to the music? His piercing imagery? His ability to set up scenes that clamor for lurid melodrama and responding waves of kitsch sentiment and then play them out with tranquil objectivity?

Created in 1954, the ballet is set to four small, unrelated pieces for orchestra by Charles Ives—eerie, idiosyncratic music that is both spare and complex. Often it seems to be a kind of ambient sound going on inside your head as you try to live in a contemporary urban America that harbors faint, fragmented echoes of its past. The ballet’s four sections are named for their music.

Central Park in the Dark: The light has almost failed in a space without boundaries. A large cluster of female figures—hair unbound, shrouded in unitards as dark and dull as mud—moves out from a faraway corner to fill the area, with the humdrum gait and pace of pedestrians in a train station. The bodies then bend over head first, kneel, and sway back and forth, crouching at intervals in fetal position. A pale bare-legged girl in a plain white sundress, “victim” written all over her, enters and picks her way through their midst as they begin to resemble tombstones or, raggedly waving their raised arms, trees in a forest rife with dangers. The girl, arms outstretched before her, fingers like antennae trying to palpate anything they might encounter, seems to be blind.

A man enters, clad like the anonymous figures. The girl goes to him immediately and, at his touch, swoons in relief or fear. Logic would have it that this lone male is the girl’s potential attacker, yet sometimes he seems as lost and terrified as she. They wander through the not-quite-human matrix as if through a tangled wood, jumping over the low obstacles formed by the bodies’ pairing up to link arms. Slowly, inconspicuously, the figures arrange themselves into a mound. Then, as the music rises to a crescendo of muted cacophony, the man flings the girl’s body onto this half-animal, half-vegetable hillock and flees. The body lies there, inert, for some terrible moments in which nothing happens. Finally the girl rises, only to return to her sightless wandering. The ensemble recedes, reassembling in its opening position way back in the space, as if the same story were about to unfold again, and the fragile girl, isolated in the middle of nowhere, walks tentatively out of our view.

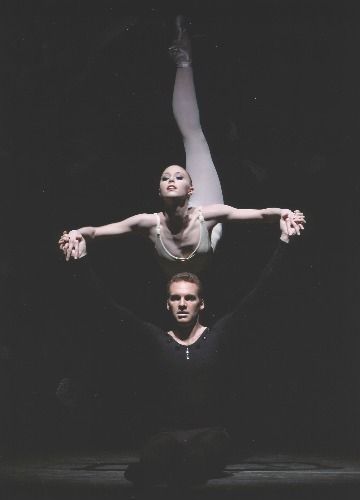

The Unanswered Question: Another dark space. Light falls on only two people. The first is a woman in a white leotard, limbs and feet bare, long hair streaming over her shoulders, face expressionless. The other is a near-naked man whose existence lies in reaching out for her eternally. The woman is an icon. She’s borne by four men swathed in black who are non-entities apart from their function. They hold her high above their shoulders, in standing or seated position, so that she resembles the statue of a saint paraded before a worshipping crowd. They swoop her downward towards her yearning pursuer, sometimes sweeping her over his recumbent body. They pass her along among themselves in a horizontal circle, as if she were a belt binding them. They wheel her backwards and bring her up head first, as if she were emerging from deep waters. Not once do they allow her feet to touch the floor.

The theme is central to Balanchine. The yearning man is the artist-lover. The woman is his muse, by definition—indeed, of necessity—unattainable. The idea is commonplace; the marvel is the way in which Balanchine has found a series of images operating in time to convey it.

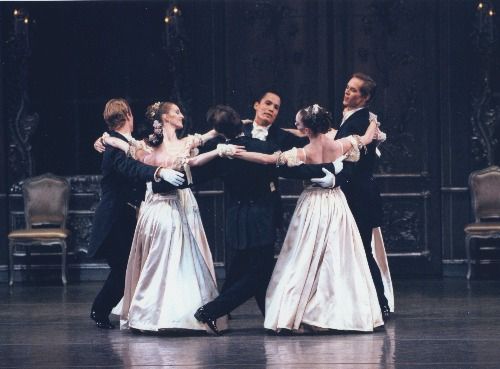

In the Inn: A man and woman meet casually at a club, enjoy a sophisticated danced flirtation—they’re worldly wise, attractive and mutually attracted—then go their separate ways with insouciance. No strings, no regrets, just that gorgeous interlude in which they charm and challenge each other and we get to watch, relishing their savoir-faire. There is no indication whatsoever of how this section relates to the darkness that prevails in the rest of the ballet. You’re left to figure that out for yourself—if you need to.

In the Night: The landscape of the first section has now become the sole action. Once again, in the gloom, the anonymous figures trudge cross-stage on their knees—until the inexorably failing light makes them invisible. Matthew Arnold’s “We are here as on a darkling plain” verses would seem to apply but for the fact that what Balanchine gives us here is not a cri de coeur like “Dover Beach,” with a proposed escape route (“Love, let us be true to one another”), but a simple, uninflected statement of fact that proves to be ineradicable.

No one mentions Ivesiana when lists of Balanchine’s masterpieces are being drawn up, but it is one nevertheless. And, half a century from the date of its making, it remains as new as tomorrow.

DANCE THEATRE OF HARLEM

An element in the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine 100 centennial celebration has been the appearance of guest artists from companies with close ties to the master. Most recently it was the turn of Dance Theatre of Harlem’s Tai Jimenez and Duncan Cooper, who dispensed their troupe’s signature warmth and graciousness in the Liberty Belle pas de deux from Stars and Stripes. Ironically, their visit coincided with the dismaying news, made public by an article in the New York Times, that DTH was in danger of folding.

While the extraordinary DTH school continues to function, the 35-year-old company, 44 dancers strong, is now operating with only a skeleton staff, there being no money on hand to pay salaries, while the board of directors has been swiftly bailing out. DTH will fulfill its upcoming engagement at Kennedy Center, June 8-13, but its future is uncertain unless sufficient funding is found to meet a $2.5 million deficit and cover the costs of ongoing production. Blame for the current fiscal shambles and the company’s lack of a sound infrastructure is being concentrated on Arthur Mitchell, the company’s founder-director, who is accused of “inept management,” according to the Times report.

Inept management? Mitchell, the NYCB’s first African-American principal dancer, conceived DTH to correct the virulent concept that blacks can’t do classical dancing, curtailed his own performing career to bring the company (and the school necessary to it) into being, and miraculously held these enterprises together for three and a half decades, leading the troupe to successive moments of glory and repeatedly getting it to rebound from near-death situations endemic to arts institutions. You call that inept management? I call it heroic achievement, and I think it should be acknowledged with admiration and gratitude—at the same time as the current grievous problems are being addressed.

Apparently, the company is now in the process of hiring an executive director, who will take care of practical matters while Mitchell, who has agreed to the arrangement, concentrates on the artistic side of the company’s affairs. This solution, simple and logical as it is in theory, may be difficult to carry out in practice, for two reasons. First, it assumes, wrongly, that there is no overlap between administrative decisions and artistic decisions. When it comes to repertory, then, will Mitchell be allowed to select or commission dances solely on their aesthetic merit? Or will he, like every other ballet director functioning today, have to give equal or greater weight in his decisions to what sells? (Ironically, Mitchell has always emphasized—purist critics would say overemphasized—ballet’s obligation to “entertain” its audience.) Second, it assumes that Mitchell will actually be able to relinquish authority on ostensibly administrative matters. From what I’ve seen, supreme authority has been essential to his achievement with DTH. Without it, and his overwhelmingly charismatic exercise of it, the company would never have existed.

In order to operate under conditions of shared authority, Mitchell will have to reshape an essential part of his personality, an element that has lain at the heart of his success. I hope he will have the courage and fortitude for this latest challenge, as he has had for so many previous ones, because his mission—making black performers an integral part of the classical-dance world—has not yet been fully accomplished. The executive director, when s/he comes on board, will need empathy for the struggle with himself that Mitchell will be undergoing and a constant awareness of the fact that even the most expert administrator could not have made Dance Theatre of Harlem happen.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias