Martha Graham Dance Company / City Center, NYC / April 14-25, 2004

If a long winter—meteorological or psychological—has scuttled your courage, you might want to check out a couple of terrific Martha Graham dances now being performed in repertory at the City Center. Cave of the Heart and Hérodiade are part of the Greek cycle that Graham created in the 1940s, spurred by the period’s newly awakened appetite for a psychoanalytical view of classical mythology. Both pieces present a pair of women, each tremendously strong in her own way, who oppose and complement each other. One is clearly the star of the show, the other secondary but essential. (It’s pertinent that both characters are female. Graham was certain her gender ran the world; men were necessary, of course, but auxiliary.) Respectively, the juxtaposed women represent the impassioned renegade and the voice of reason that attempts to dissuade that reckless iconoclast from her dire purpose.

In Cave of the Heart, revived this season, Medea, her ferocious jealousy ignited when her husband, Jason, transfers his affections to an ingenuous young princess, devises a hideous death for her rival and murders her own—and Jason’s—two young sons. (Though the latter deed is not actually shown, Graham could assume her audience knew these stories.) The Chorus, in the form of a single stately woman, tries at length to deflect her from what she has resolved to do. And fails. Not for lack of trying. Not because the Chorus is wrong; it’s not; it has reason—and all of civilization—on its side. The Chorus fails because there is no stopping the raging spirits Graham embodied. The whole point of them is that they’re beyond reason, incapable of being contained. If a little self-immolation is involved, a female hero of this ilk says to herself, so be it. She is, in Graham’s words, “doom-eager.” Graham probably knew, too, if only in her secret heart, that wreaking disaster is a form of self-expression.

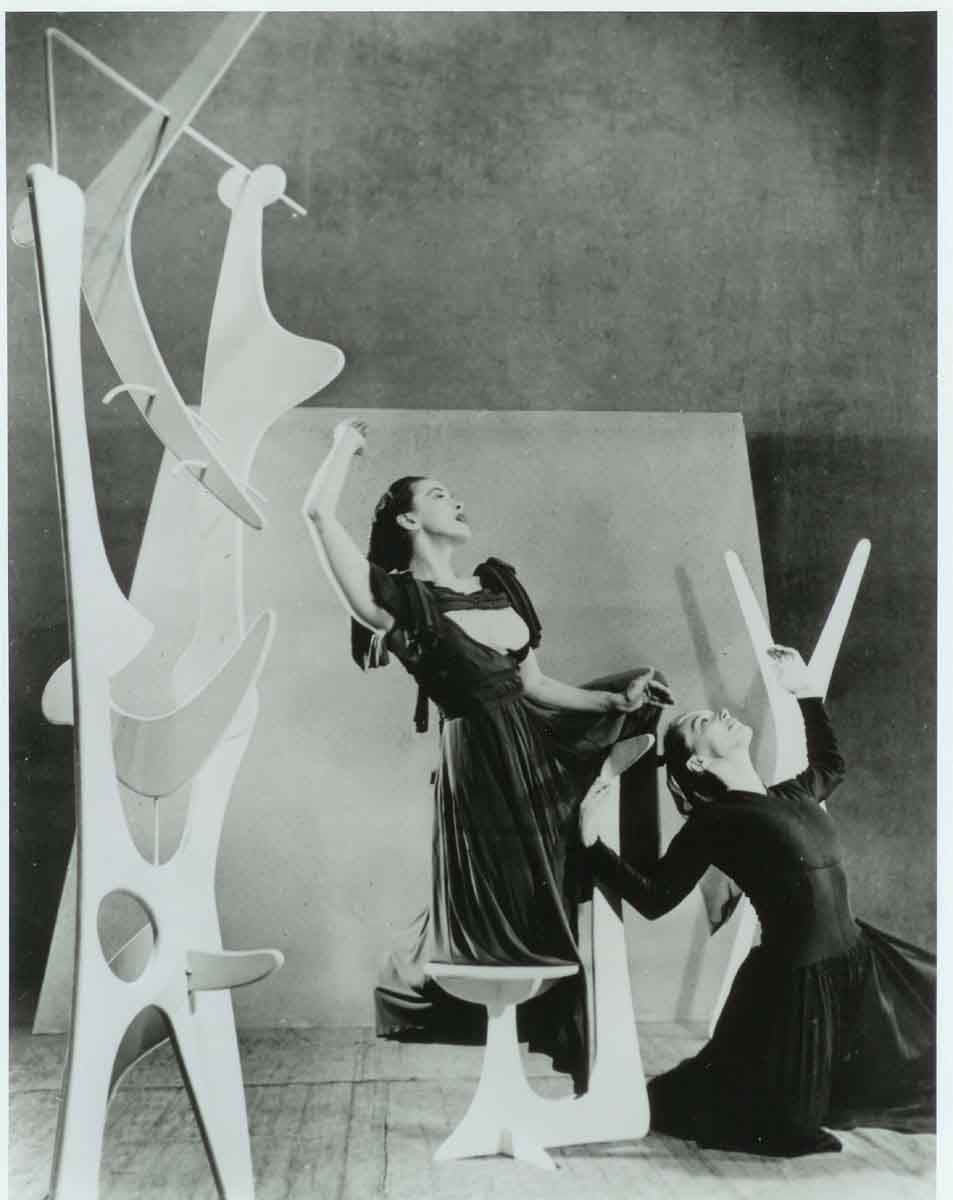

Hérodiade reduces the nature of the two women and their relationship to its essence. The pair constitutes the cast in its entirety, and ties to the St. John the Baptist narrative are all but abandoned. The Hérodiade figure is simply a daring soul in crisis, examining herself—laying her bones bare, as the set’s anatomical “mirror” sculpture suggests—and deciding to commit herself to a fateful action. The other woman fills the role of confidante and counselor, servant and protector. She personifies the wisdom of the world on how one may live placidly, which is all most people ask of their existence. Don’t embark on that path, she seems to be saying. Think of the consequences. The Hérodiade figure, of course, stands for the life lived fully, in defiance of good sense, in accordance with one’s deepest impulses. Hérodiade falters—Graham deepens the character as well as the drama by showing us that—then repossesses her resolve and goes to her destiny, radical and intrepid. Talk about role models!

Hérodiade reduces the nature of the two women and their relationship to its essence. The pair constitutes the cast in its entirety, and ties to the St. John the Baptist narrative are all but abandoned. The Hérodiade figure is simply a daring soul in crisis, examining herself—laying her bones bare, as the set’s anatomical “mirror” sculpture suggests—and deciding to commit herself to a fateful action. The other woman fills the role of confidante and counselor, servant and protector. She personifies the wisdom of the world on how one may live placidly, which is all most people ask of their existence. Don’t embark on that path, she seems to be saying. Think of the consequences. The Hérodiade figure, of course, stands for the life lived fully, in defiance of good sense, in accordance with one’s deepest impulses. Hérodiade falters—Graham deepens the character as well as the drama by showing us that—then repossesses her resolve and goes to her destiny, radical and intrepid. Talk about role models!

Having created such female heroes for herself—not only on her own idiosyncratic body, in a vocabulary she invented for the purpose, but also from her own ecstatic mindset—Graham inevitably set up a succession problem. What dancer was dynamic enough to inherit these parts and inhabit them as they deserved? A glorious few live in the memory of veteran fans. Today’s answer to the question is Fang-Yi Sheu, who, this season, is reanimating the title role in Hérodiade.

Born and initially trained in Taiwan, Sheu is a small, delicately boned woman with powerhouse strength and laser beam concentration. Her face has the theatrical impact of a Noh mask. In all of this she resembles Graham. One hardly knows what to marvel at first—the sheer technical command (her ability, for instance, to spring from one shape to another without any visible transition), the psychic capacity that enables her to maintain intensity even in stillness, or the dramatic power, which draws the viewer inexorably into the world of her imagination and holds him there, riveted, until at the end of the dance she lets him go, shaken and quite possibly changed forever.

Wisely, the company confined the repertory chosen for the current season almost exclusively to the great works of Graham’s early and middle periods. This strategy ensured that nearly all the sets on view would be the stunning sculptural inventions of Isamu Noguchi—an added advantage. Nevertheless, management decided to revive Circe, a later and lesser affair—perhaps to show off the bodies beautiful of the men it now has on hand. Ulysses, who sails into the realm of the evil enchantress (ironically in a Noguchi set recycled from an earlier, failed, dance), was played by Kenneth Topping as a straight arrow, while his Helmsman (David Zurak) appeared uncomfortably undecided as to his own erotic inclinations. But the crew, already transformed by the lethal lady, when we encounter them, into Snake, Lion, Deer, and Goat—well, my dear . . .

The Graham legend, a mythology in its own right, contends that she combined the Puritan and the sensualist in her makeup; ostensibly this made her an authority of sorts on forbidden games. Today, forty years after the premiere of Circe, its would-be sexy parts seem dopey to the point of embarrassment. The hero’s choosing to couple up with the ostensibly seductive witch bitch (a gimcrack figure in a gold maillot and firehouse-red cape) appears downright illogical; surely the extended soft porn shenanigans are setting him up for a frolic with the Helmsman. Snake, Lion, Deer, and Goat (Martin Lofsnes, Whitney Hunter, Christophe Jeannot, and Maurizio Nardi, respectively, the night I went), clad only in bikini trunks and face paint, were indeed ravishing to ogle. I’m happy to report that they danced with a grave beauty their circumstances hardly encouraged.

A third revival, The Owl and the Pussycat, proved, for any newcomer to Graham’s domain, that the choreographer had no gift for entertainment in the blithe gaiety mode. She could be mordantly witty—as in Acrobats of God, where she played herself, only slightly exaggerated, in the role of a driving ringmaster who has brought the cult of her own personality to the same fever pitch as her dancers’ skills. But the lightweight and the lighthearted lay beyond her.

Like Maple Leaf Rag, also included in this season’s repertory, presumably to leaven the dark psychological turbulence of Graham’s finest works, O&P was resurrected with André Leon Talley—Mr. High Style—speaking the familiar Edward Lear verse that the choreography illustrates with suffocating whimsy. A gentleman of impressive height, bulk, and panache, in still more impressive clothes (tweeds, cape, spats—contrived by Ralph Lauren), he was a sight to see, as were some charming moves the choreographer contrived for a trio of mermaids. (Unmentioned by Lear, these delectable, bipedally challenged creatures are viewed by the dance’s protagonists from their “beautiful pea-green boat,” contrived, in Noguchi-lite mode, by Ming Cho Lee.) Still, this is not the sort of concoction you want to encounter more than once in a decade. As for Maple Leaf Rag, I went home before its forced good cheer could be foisted upon me.

Photo credit: Arnold Eagle: Martha Graham (left) and May O’Donnell in Graham’s Hérodiade. Set by Isamu Noguchi.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias