Johannes Wieland / 92nd Street Y Harkness Dance Project at The Duke on 42nd Street, NYC / March 10-14, 2004

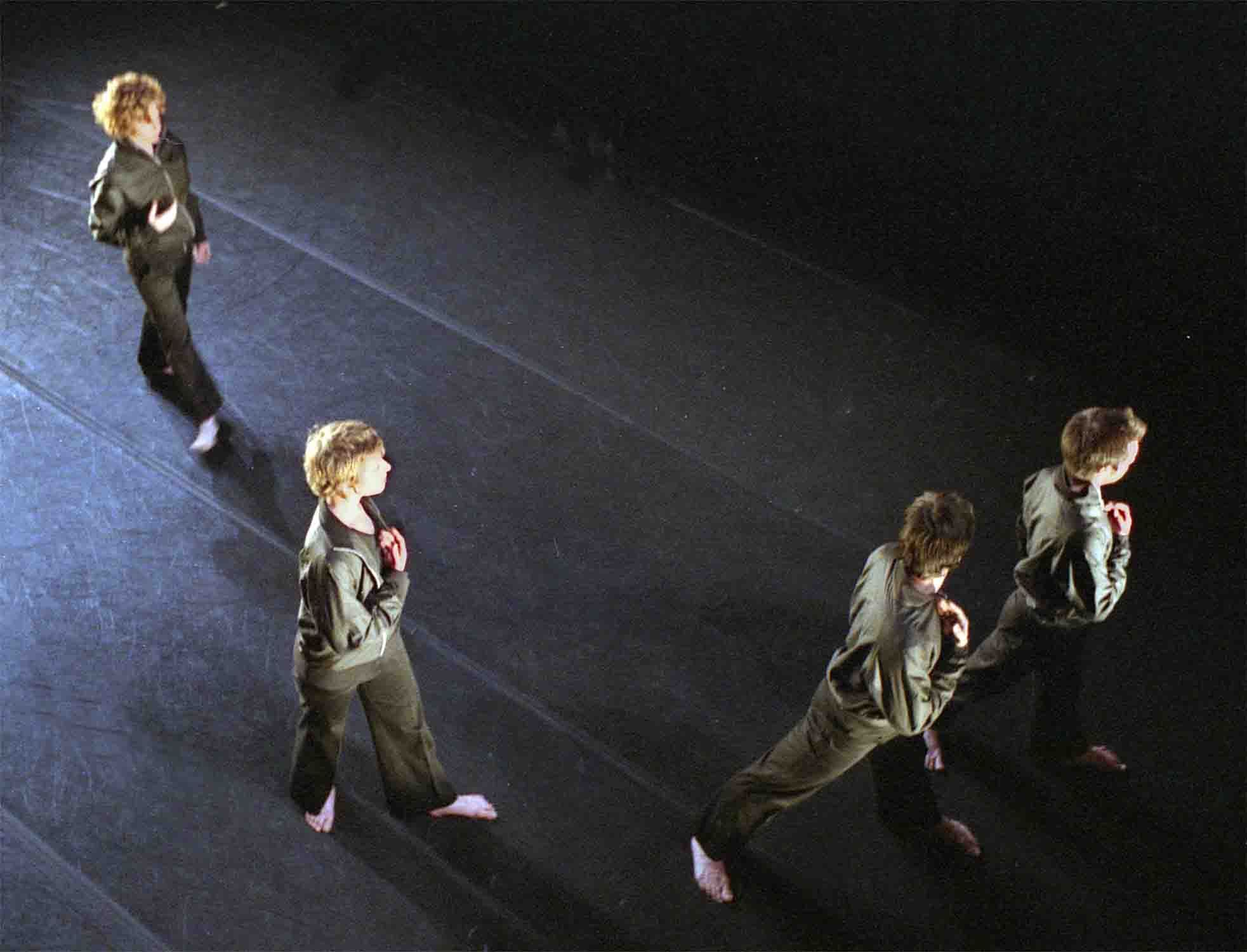

When Johannes Wieland operates in his signature style, he makes dances that are immaculately pared down and aggressive to the point of violence. Adamantly abstract on its surface, the work is haunted by subtle currents of emotion. His best achievement to date in this vein in the new Membrane, for eight black-clad dancers in a black-box void, only their faces, hands, and bare feet luminous as the moon in a midnight sky.

The figures are outfitted identically in jerseys, trousers, and windbreakers. Those chest-hugging zip jackets, though, are as much prop as costume. And they evolve, as the action develops, into a metaphoric skin—tough but capable of being shed or penetrated—that encloses and isolates the individual, cloaking his vulnerability to the effect of others, thwarting real connection.

The piece opens with a prologue of sorts. The man and woman who will prove to be the central couple (Julian Barnett and Eliza Littrell) maneuver each other into and out of their jackets, twisting and twining like a pair in a rubber-jointed circus act. Then the rest of the cast galvanizes into movement—sudden, powerful, and raw—that makes you think of gang warfare. Repeatedly, one dancer flings another’s weight around his body, finally positioning the partner high on his shoulders. The ploy suggests that their roles have abruptly reversed, slave becoming master, victim becoming terrorist.

The dancers group into duos, trios, quartets that reveal Wieland’s inventive command of structure. (He actually makes good on his press materials’ lofty declaration that he employs “an architecturally driven understanding of bodies, movement, and space.”) One trio, replicated by another in greater shadow, has dancer A supporting dancer B in a burly grasp so that B, predatory legs scrambling in the air, can tread up and down dancer C’s body as C stands riveted in place, stoically tolerating the repeated aggression. Then Wieland adds the two remaining cast members, who’ve stood immobile on the outskirts of the scene, like bystanders at a horrific event who can’t stop watching but do nothing to intervene or turn their backs, stonily refusing the role of brother’s keeper. And at this moment Wieland exercises his true gift. He gets you to quit admiring his organizational acumen and feel what a tough world these figures (indeed, all of us) inhabit, physically and psychologically. He has you walking right down those mean streets.

Eventually the dancers shed their windbreakers, and much is made of the stripping (usually at another’s hand) and of the garment stripped, which the owners continue to animate—viciously flinging it about, nuzzling it like a child with his “blankie”—even though they’re no longer wearing it. The shedding of the protective shell and the ensuing ridding the self of it—so that it’s not merely gone from the wearer’s back, but no longer in his possession–leads only to more violence, which builds to a frenzy. So much for the romance of attaining maturity.

In what you might call a coda, the dance refocuses on the main couple, now alone in the gloomy arena. Having, with the greatest difficulty and effort, laid themselves bare, they reap no reward. Instead, they’re consigned to continue their hard-won togetherness in a void of endless inconsequential repetition, treading in an amorphous space with no destination. It’s a suitable latter-day ending for a latter-day condition. Wieland neither sentimentalizes nor overdramatizes it. This calibrated reticence is a key aspect of his talent. He need only beware that it doesn’t stifle him.

Occasionally Wieland ventures into modes quite different from the one Membrane epitomizes. Another new piece, Filtrate, uses three distinct generations of dancers; eerily lit Plexiglas boxes that serve as cages for the participants; and an absurdist text involving a freezer, memory, and ice cubes. For the first third of its 27 minutes, while I was still making my best effort to scrutinize it, I found it inscrutable. After that, I found it affected and dull. But, though I would never willingly watch this piece again, I’m not railing at Wieland for making it. Like ordinary folks, choreographers have to explore paths that may lead them to swampland, even quicksand, in order to get where they’re really meant to go.

Photo credit: Sebastian Lemm: Isadora Wolfe, Eliza Littrell, Branislav Henselmann, and Julian Barnett in Johannes Wieland’s Membrane

© 2004 Tobi Tobias