Stephen Petronio Company / Joyce Theater, NYC / March 23-28, 2004

The press release for Stephen Petronio’s latest creation, The Island of Misfit Toys, being given its first New York showings at the Joyce, promised “themes that include obsession, guilt, insatiable desire and the mundane details of life.” The night I went, the crowd seemed wary—baffled perhaps—and gave it a lukewarm reception. C’mon, what’s not to like?

The press release for Stephen Petronio’s latest creation, The Island of Misfit Toys, being given its first New York showings at the Joyce, promised “themes that include obsession, guilt, insatiable desire and the mundane details of life.” The night I went, the crowd seemed wary—baffled perhaps—and gave it a lukewarm reception. C’mon, what’s not to like?

For some eloquent London critics writing at its premiere last year, the piece epitomized the downtown New York Zeitgeist—all glamorized dysfunction, decadence, and desperation. As with the solo Broken Man and City of Twist, two works from 2002 that shared the Joyce program (called “The Gotham Suite”), Toys proves Petronio to be a canny practitioner of a genre I’ve come to think of as KinkyChic. And, as is his wont, the choreographer has enlisted big names to bolster the edgy quality he lays claim to. The score is drawn from Lou Reed numbers; the set comes from Cindy Sherman; the costumes, from Imitation of Christ’s Tara Subkoff.

What’s not to like? Well, I have two complaints, both of them serious. One: Petronio substitutes fashion (not just clothes, but lifestyle, to use a relevant trash word) for meaning and feeling. Two: The dancing he devises—while executed with stunning fluidity, speed, and strength—is extremely limited in vocabulary, rhythmic interest, and structure. Not surprisingly, Toys is most telling in occasional images that would make reasonably potent shots in a latter-day glossy.

Sherman sets the scene with a pair of grotesque doll-like sculptures that loll on the apron of the stage, one huge-bellied with extra limbs and two pin-heads, the other with a gigantic head that sports a gaping hole where the face should be. Later she projects a totem pole of baby faces onto the backdrop. Each is rendered as a plump infant-Buddha mask, its impassivity distorted by fear, delight, rage, or grief. The visages evoke horror because, contrary to popular wishful thinking about the sweetness and innocence of the very young, people six months old really look like this as they experience primal emotions with unalloyed force. This photographic collage struck me as being the single genuine element in the show.

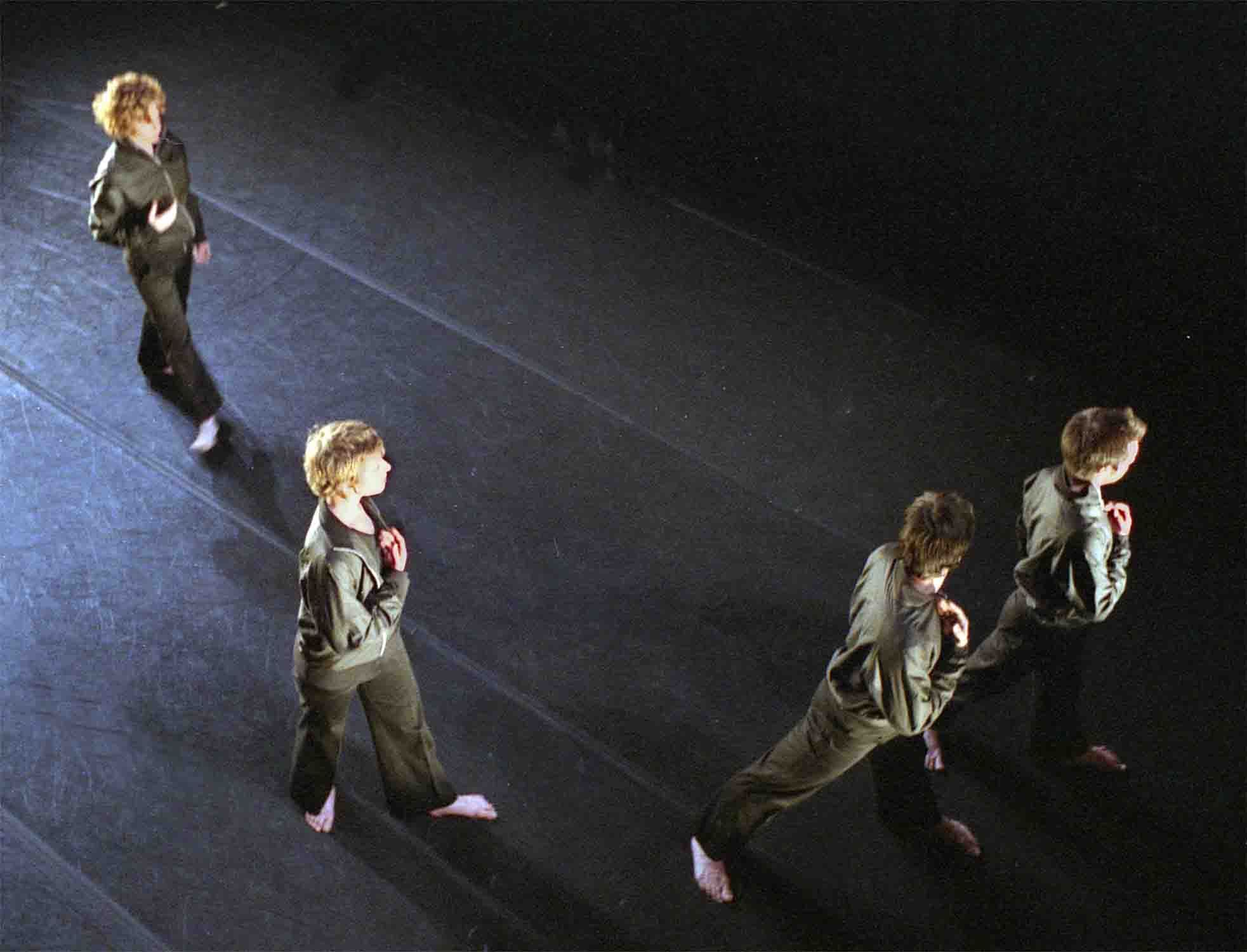

As the piece opens, Petronio—head shaved, sleek body outfitted in menacingly weird evening dress—lolls in a chair, back to the audience, smoking as he scrutinizes a bunch of figures with unreliable spines. He might be a PoMo Diaghilev auditioning prospects for his company. But, as if in a wannabe reference to E.T.A. Hoffmann’s riveting tales of the subhuman, the hapless dolls—creations, perhaps, of the Petronio character’s own imagination and ingenuity—come to half-life and wrest away his power.

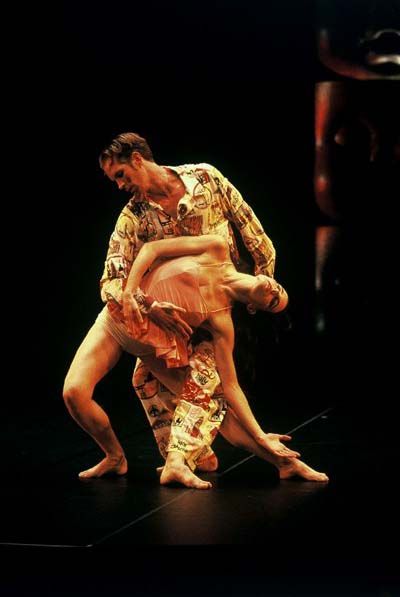

The balance of the piece chronicles the gradual disintegration of the dolls—pajama-clad bodies inclined to mildly depraved sexual practices and an increasing impairment of their sense of center. As their physical coordination diminishes, they lose harmony, eloquence, purpose—in other words, the traits, based on connection, that define civilized beings. The dehumanization process goes on at a length that could only hold the attention of a voyeur, and I think Petronio casts his audience in that role. He doesn’t elicit empathy for, or even understanding of, the creatures in his garish, disjunctive parade; he offers the stuff up merely as titillating entertainment. Oddly enough, his inventions aren’t strong or singular enough to fill the bill.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

Photo credit: Angela Taylor: Gino Grenek and Jimena Paz in Stephen Petronio’s The Island of Misfit Toys

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely-Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless-to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?

Le Grand Puppetier, being given its world premiere, takes off from Fokine’s Petrushka, a key work in the dance canon created in 1911 for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, which starred Vaslav Nijinsky in the title role of the puppet who proves to have an immortal soul. Ingeniously, Taylor uses Stravinsky’s pianola version of the score he created for the Fokine ballet. Then, confusingly, Taylor junks Fokine’s libretto, while appropriating some of Fokine’s characters, so that viewers familiar with Petrushka will be driven to distraction by the matches and mismatches, while viewers unacquainted with the Fokine are likely-Taylor’s plot being improbable and pointless-to remain in the dark. Why, they may well wonder, is the Emperor, as Taylor calls his Puppet Master, bent on marrying off his daughter to a gay fop? Is it likely that the Emperor’s pathetic Puppet would (1) overthrow his master’s tyrannical regime and, (2) having done so, cede control back to the dictator?