New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

The Sleeping Beauty, that touchstone of classical ballet, addresses and illuminates several absorbing issues—among them, hierarchy. This is only natural. The work was created in 1890 in St. Petersburg. Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky, its composer, and Marius Petipa, its choreographer, lived and worked under the rule of the tsars. And classical ballet itself, in its training methodology and in the operation of the institutions that make it possible at its highest level of evolution, depends upon hierarchy—upon systematic development and the ordering of greater and lesser into a strong, self-confident whole.

The New York City Ballet’s production of Beauty—on display for two weeks to close the first half of the company’s Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration—is not by Balanchine, but by Peter Martins. Apart from its function of selling tickets—I hadn’t seen so many little girls assembled to witness a theatrical spectacle since I’d been to the ice show—it was included in the season to represent Balanchine’s heritage. The original Beauty was one of the glorious products of the Maryinsky Theatre, in whose academy the young Balanchine was bred.

The Sleeping Beauty proposes the court of the fictive King Florestan and his queen as a macrocosm, a hierarchical universe in itself. Attendants to the great are everywhere present in it. Beginning at the beginning—the christening of the royals’ infant daughter, Aurora—tiny, seemingly genderless pages bear the reigning monarchs’ trains, heads held high, chins thrust forward, feet busily working as they, probably first-year pupils in the company’s academy, progress in the adults’ footsteps. Soon slightly more substantial pages appear, bearing ornate cushions on which repose the gifts each of the fairies offers to the newborn princess. Just as a pair of nursemaids hovers over Baby Aurora, an octet of fairies-in-waiting accompanies the Lilac Fairy who will save, sustain, and bless the royal offspring’s life. Carabosse, the wicked fairy, is appropriately seconded by a team of jet-black insects who not only draw her carriage but also scuttle around her, metallic carapaces glittering, exuding, like a noxious fog, an atmosphere of fear and corruption. Even Little Red Riding Hood, one of the fairytale characters summoned to grace Aurora’s wedding, played by the most minuscule child imaginable, has a retinue of just slightly more robust children to play the trees of the forest that’s the scene of Perrault’s vulpine melodrama.

The Garland Dance, performed at the celebration of Aurora’s coming of age, is a veritable lesson in hierarchy. In the NYCB’s Beauty it is the one segment choreographed by Balanchine (after Petipa, of course). Here 16 pairs of adult men and women—their costumes executed in garden tints and adorned with flowers—waltz in unison, manipulating stiff semi-circular hoops festooned with blossoms. As soon as their charm has registered, they’re joined by 16 little girls with flexible flower chains that evoke the tender new growth trees sprout in spring. Eventually eight adolescent-looking girls are added to the picture, and the stage becomes a strictly organized floral tapestry—the geometric patterning recalling the formal gardens of the seventeenth century—its design shifting kaleidoscopically. Beyond the sheer prettiness and ingenuity of the display lies a clear message about the scrupulously calibrated stages of growth through which a ballet pupil must move to attain even a first foothold (corps de ballet rank) in the company and the strength such an institution acquires through each of its members and aspirants having and knowing her place.

Throughout the ballet there are myriad examples (in the many soloist roles and principal parts) of the further stages possible in a dancer’s development as well as rich evidence of the variety of functions to which a dancer may be assigned (technical virtuoso, soubrette, character dancer, mime), according to his or her particular gifts.

Today’s audiences finds the neophytes—the bevy of diminutive Garland Dance girls in their floppy pink skirts—irresistibly cute, and indeed they are. I just wish the same viewers would take a moment to think about what these very young children represent—how poignant their commitment to their goal is in a world that now scorns the restrictions necessary to hierarchal order, how fragile and unpredictable the artistic future of each child is, and how necessary they all are to the continuity of their art form.

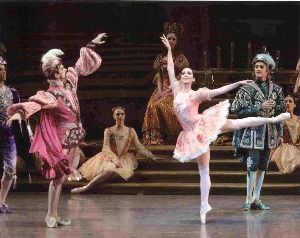

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Jenifer Ringer as Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty (choreographed by Peter Martins, after Marius Petipa; Garland Dance choreographed by George Balanchine)

© 2004 Tobi Tobias