New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

At the time of its creation for the New York City ballet in 1967,  Balanchine’s Jewels was much touted as the first program-length plotless ballet ever. The claim—good marketing fodder, like the anecdotes about the choreographer’s “fondling” a cache of gems, courtesy Van Cleef and Arpels—is tenuous. It is actually three discrete ballets—Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds—each independent of its sisters, as we saw subsequently, when Rubies successfully entered the repertory of other companies as a stand-alone.

Balanchine’s Jewels was much touted as the first program-length plotless ballet ever. The claim—good marketing fodder, like the anecdotes about the choreographer’s “fondling” a cache of gems, courtesy Van Cleef and Arpels—is tenuous. It is actually three discrete ballets—Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds—each independent of its sisters, as we saw subsequently, when Rubies successfully entered the repertory of other companies as a stand-alone.

The distinct difference among the segments of Jewels is the music, which calls on various aspects of Balanchine’s style—the French Fauré for the evocative, Romantic Emeralds; the American Stravinsky (like Balanchine, a Russian transplanted to New York) for the brash, jazzy Rubies; the nineteenth-century Russian Tchaikovsky for Diamonds. The latter two composers, of course, were Balanchine’s closest collaborators.

The segments vary in strength. Diamonds has always seemed to me to be the weakest—a reiteration of familiar Petipa-derived devices, apart from its poignant pas de deux—but that’s partly because it doesn’t hold a candle to another Balanchine evocation of the grandeur of imperial Russia (and the imperial Russian ballet), Tschaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 (né Ballet Imperial). Rubies epitomizes the New World breakneck energy and syncopated rhythm that seized Balanchine’s imagination when he emigrated to urban America and fueled it for the rest of his career. The haunting Emeralds, conjuring up love not as it is, but as it’s remembered, has always been my favorite. In atmospheric force, its price is above rubies.

Originally, the unifying element of Jewels, apart from Balanchine’s sensibility, was the set—overhead, the same simple jewel-bedecked sky, below a cleared space for the action, the lighting shifting from green to red to white, according to the gem being celebrated. Peter Harvey, who created that décor, has come up with a new one for the Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration. Program notes claim that it’s meant to make the ballet look more contemporary (as if it needed cosmetic surgery!). What it does is intrude upon the choreography’s air space and, egregiously, like those extended labels for art works in museums, “interpret” the nature of the individual ballets (as if such choreography needed explaining!).

Emeralds, once “a green thought in a green shade,” has acquired a backdrop suggesting a woodland park, with strings of vulgarly enlarged brilliants looped overhead, as if for a low-end fête champêtre. Rubies, a seize-your-eyes ballet, must now fight for attention with a vicious abstraction of narrow vermilion columns that pierce the space vertically like exclamation points and crisscross in the heavens to fence in a fiery thundercloud; red glitter-glue is applied here and there for entirely superfluous emphasis. Diamonds has been converted to Snow, with backdrop and side pieces a wallpaper of white swirls against a meteorologically incorrect blue sky. An etching of black lines, like a beginner’s efforts with ruler and compass, provide a visual equivalent of static, while the requisite sparkling gems assemble themselves as overgrown snowflakes. The effect is everywhere ugly and claustrophobic.

As for the dancing in the current production of Jewels, there’s no point in my reiterating the complaints I’ve already made in this “Balanchine at Home” series about unfathomable casting, the lack of an empowering vision about the ballets, and the lamentable absence of coaching from the originators of the great Balanchine roles. I’d rather concentrate on some very good and interesting dancing in the two casts I saw.

In Emeralds, Miranda Weese, cast against type in the role Violette Verdy originated, was technically immaculate, cold, and voluptuous. She gave every phrase its carefully considered due and, by her second performance, had loosened up just enough, gained sufficient confidence in what she was doing, to make this carefully thought out rendition heart-catching. Of all the dancers I saw in Jewels this time round, Weese, from whom I’d least expect it, was the only one who made me feel the surge of profound, complex emotion, inexpressible in words, that used to be an all-but-guaranteed experience in watching Balanchine. I also admired Pascal van Kipnis in the pas de trois, where she captured the strange and wonderful combination of devotion to classical form and delight in sheer decoration typical of French culture.

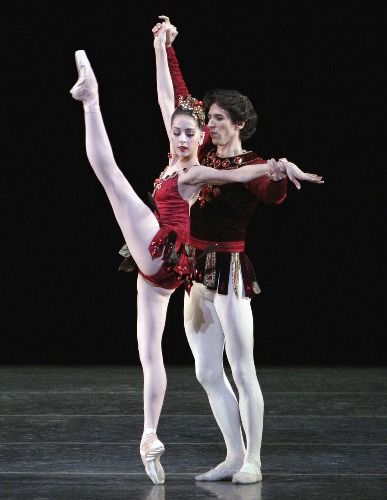

Alexandra Ansanelli and Damian Woetzel can’t compare to Patricia McBride and Edward Villella, the original central pair in Rubies, who made their performance a glorious duel of wits. Still, this new team is altogether up to its assignment in terms of bravura technique and sensitivity to maverick timing. Woetzel needs to recover the street-smart aspect of his dancing persona evident in the brash performances of his early career, while Ansanelli, a very young principal, needs only someone to assure her she doesn’t have to be darling.

The tall, odd-girl-out role was entrusted to a relative newcomer to the company, Teresa Reichlen. She’s a throwback to a Balanchine type—pinhead, incredibly long legs—that the company no longer cultivates with ardor, though some key roles in the rep are based on it. The type, which Balanchine probably extrapolated from the image of the American showgirl—comes in two varieties: sharp and brittle or luscious. Reichlen, with her lush thighs and uncanny pliability, belongs to the latter group. She’s part goddess, part freak of nature, and, perhaps because she’s still inexperienced, seemingly innocent of her own effect. I’ve never seen anyone I’ve liked as much in this role.

In Diamonds, Maria Kowroski, City Ballet’s adagio specialist, with Philip Neal as her cavalier, made the pas de deux elegant and meaningful, a privileged glimpse into the very nature of a tsarina—a young woman subject to the urgings of love and the obligations of aristocratic duty, whose responses are all the more touching for being cloaked in exemplary behavior. Now I’ve gone and made the ballet sound as if it enacts a story. No, it’s both plotless and characterless, free from any of the literal stuff that can be pinned down in a program note. But the genius of Balanchine ensures that every viewer, on every viewing of Diamonds, can derive a new story—as well as new personas and new implications—from the rich store of potent suggestions the choreographer has planted in the ballet, all the while claiming that he was simply responding to the dictates of the music.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Alexandra Ansanelli and Damian Woetzel in George Balanchine’s Rubies

© 2004 Tobi Tobias