“Fashioning the Modern Woman: The Art of the Couturière, 1919 – 1939” / The Museum at FIT, NYC / February 10 – April 10, 2004

“Temptation, Joy & Scandal: Fragrance & Fashion 1900-1950” / The Museum at FIT, NYC / February 24 – April 10, 2004

Valerie Steele’s argument is couldn’t be simpler. In the two-decade period between the World Wars (1919-1939), she points out, couturières, not couturiers—gals, not guys—dominated the field of designing for women. Before that, males held sway, as they have ever since. “Fashioning the Modern Woman,” the pleasurable exhibition Steele has curated for the Museum at FIT, reveals the depth, richness, and calm self-confidence of women’s achievement in this halcyon period. It does so with minimal supporting text and no theoretical fanfare whatsoever, but simply by offering up the primary evidence—garment by garment, the individual pieces chosen with sharply honed taste and then tellingly juxtaposed.

Represented here are the names everyone knows: Chanel, Schiaparelli—and then singular talents who are not quite household words, Madeleine Vionnet, Jeanne Lanvin, and Alix Grès. Others are familiar only to historically minded devotees of costume, among them the pair with conjoined names, Augustabernard and Louiseboulanger; Jeanne Paquin; Maggy Rouff; and the sister teams of Callot and Boué, whose collaborations might be the stuff of fairy tales. (The Boués called their house fragrance Quand les Fleurs Rêvent—When Flowers Dream.) And there are some about whom almost nothing is known, though their designs survive, bearing witness to their gifts.

Trace the winding path in the larger of the two rooms devoted to the exhibition (the entry chamber offers a historical prologue), and you encounter a parade of elegant, often innovative dresses and gowns, not one of them outlandish, each capable of transforming its wearer into a piece of poetry. If you can wrench your attention away from the sheer beauty and understated luxe of the display, you’re bound to be impressed by the element of conceptual invention.

A quartet of Augustabernard dresses from the early Thirties—one for day, three for evening—is an exercise in simplicity, at once adamant and lovely. It limits its collective palette to pale dusky peach (the hue changing according to the reflective differences between satin and crepe), matte black, copper, and a plum to which velvet lends added lushness. Like Vionnet, Augusta Bernard was a master of the bias cut, and her creations, fashioned for a willowy figure, drape as if nature allied them to the female anatomy. The dresses cling here, expand into a vertical column of fluid ripples there, giving a poignant delicacy to the figure, especially at the collar bone, the exposed shoulder blades, and the boyish hips. The hems are uneven, descending in back to make the faintest suggestion of a train—the sign, perhaps, of a princess in exile. The aggressive print of the day dress (at a distance it suggests hound’s-tooth check) is a wry joke, since the fabric is fine and the draping a marvel of lyric grace, while a little flourish of fabric at one shoulder looks like a cross between an epaulet and an angel’s wing.

The parade of 15 Chanels alone will make you want to set fire to your closet and will reveal to all but the most erudite costume aficionado a heretofore unappreciated range of the woman’s genius. Chanel’s concepts, as this display demonstrates, went far beyond the style tropes  for which she’s famous—and imitated. One example that held me in thrall was—is, it’s permanently burned into my imagination—a long black evening dress in which silk velvet, a fabric that manages to be dense and delicate simultaneously, describes a pinafore shape on the body. Inserts of fine-gauge black tulle, folded irregularly over flesh-colored material, are used for sleeves that stop, oddly, just above the elbow and for side panels at the torso, where the ribs house the lungs, as if these segments of the body had been exposed by x-ray. Velvet crops out again just beneath the shoulder, in a gathered flourish that cascades along the upper arms, like the petals of drooping flowers. The neckline plunges recklessly, and the back of the dress is slashed nearly to the waist, baring the spinal column. One imagines that, on a live woman (as opposed to a plaster mannequin), the vertebrae seemed to be transformed into eerie jewels. This is the sort of dress that makes you feel no other need exist.

for which she’s famous—and imitated. One example that held me in thrall was—is, it’s permanently burned into my imagination—a long black evening dress in which silk velvet, a fabric that manages to be dense and delicate simultaneously, describes a pinafore shape on the body. Inserts of fine-gauge black tulle, folded irregularly over flesh-colored material, are used for sleeves that stop, oddly, just above the elbow and for side panels at the torso, where the ribs house the lungs, as if these segments of the body had been exposed by x-ray. Velvet crops out again just beneath the shoulder, in a gathered flourish that cascades along the upper arms, like the petals of drooping flowers. The neckline plunges recklessly, and the back of the dress is slashed nearly to the waist, baring the spinal column. One imagines that, on a live woman (as opposed to a plaster mannequin), the vertebrae seemed to be transformed into eerie jewels. This is the sort of dress that makes you feel no other need exist.

A cluster of creations by Jeanne Lanvin almost equals the Chanels and is as eye-opening about the designer’s range. Though beautiful, much of Lanvin’s work seems bound to its time. Not so here. A trio of evening dresses, ankle-length and slim-lined, plays on the infinite possibilities possible in the manipulation of a mere three basic ingredients: black silk net, black silk tulle, and black paillettes (some square, some round). The resulting garments, playing on the contrast between translucent and opaque in costume’s most powerful hue, evoke seduction and armor, an inviting vulnerability and an arrogant glamour. Created in the early Thirties, these dresses would turn heads today even in the trendy restaurants and clubs of New York’s meat-packing district, where appearance is everything and the notion of chic is updated hourly.

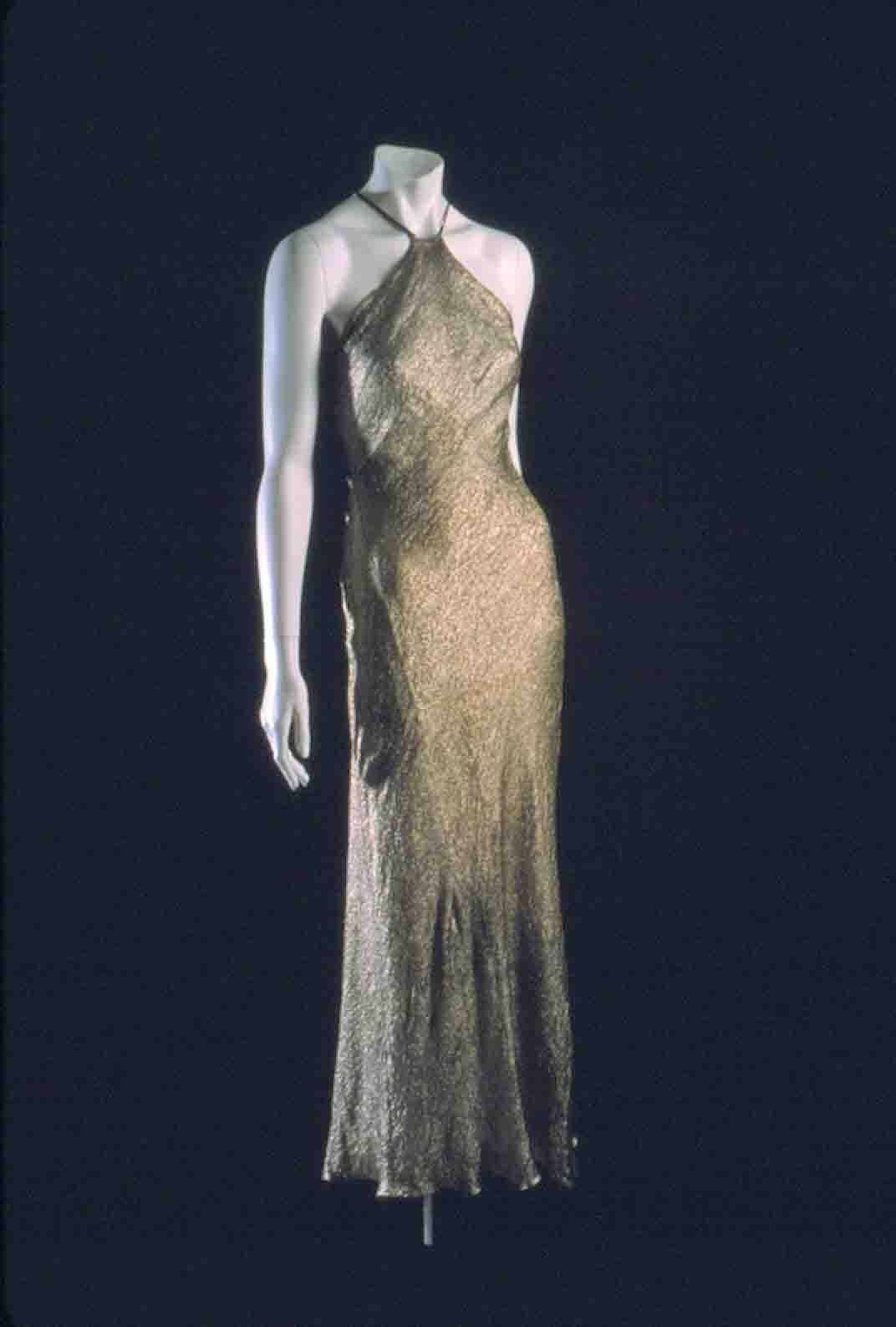

My own taste leans to the simple and severe—to an emphasis on cut rather than adornment, to matte black rather than satiny pinks, but if it’s pretty you favor, there’s plenty of it here too: dresses that are effusions of poppies and roses; tributes to ancient Greece executed in metallic lamé; homages to the harem elaborated with beaded embroidery; even a handful of jeunes filles en fleurs affairs. In the hands of Vionnet, this last genre is treated so subtly, it achieves an immense sophistication, despite the sherbet tints.

Complementing this show is an exhibition rakishly titled “Temptation, Joy & Scandal,” with the subtitle “Fragrance & Fashion 1900-1950” to ground it. It was curated by FIT’s graduate students, but is no more an apprentice affair than the annual Workshop Performances of the School of American Ballet.

The modest available space has been transformed into a cave of dull-finish midnight blue that virtually swallows light. The soft, suggestive darkness is illuminated only so that a host of vitrines—poised so the visitor gazes not frankly at them but down into them—glow with their myriad scrupulously arranged treasures. Exquisitely fashioned bottles (collector’s items today) and their ingeniously contrived packaging gleam like Aladdin’s hoard, a medley of clear and etched crystal, burnished old gold, insouciantly painted flowers, and sleek stinging lacquers of Chinese red and implacable jet, here and there accented with turquoise and lapis lazuli. The show offers the requisite measure of scholarly reportage (and its excellent complimentary brochure, even more), but the presentation itself, aptly taking its cue from the nature of scent, is sheer enticement.

Photo credit: Irving Solero: (1) Madeleine Vionnet: Evening dress, silk lamé, c. 1938; The Museum at FIT, gift of Mrs. Rodman A. Heeren; (2) Gabrielle Chanel: Evening dress, black silk velvet and black silk chiffon, 1932-33; Museum of the City of New York, gift of Mrs. Harrison Williams

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

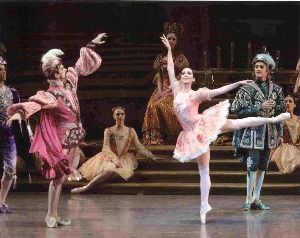

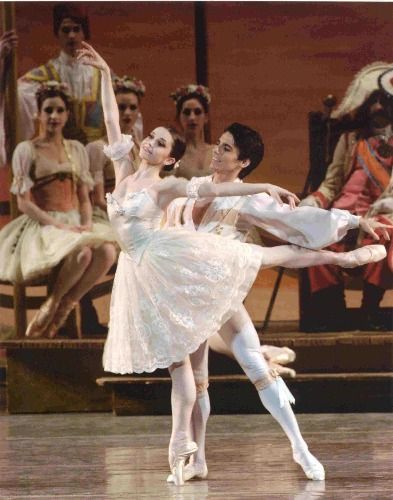

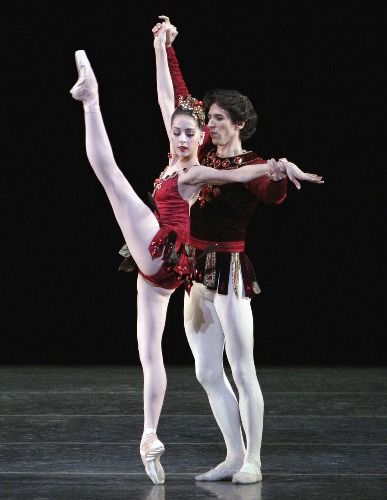

Balanchine’s Jewels was much touted as the first program-length plotless ballet ever. The claim—good marketing fodder, like the anecdotes about the choreographer’s “fondling” a cache of gems, courtesy Van Cleef and Arpels—is tenuous. It is actually three discrete ballets—Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds—each independent of its sisters, as we saw subsequently, when Rubies successfully entered the repertory of other companies as a stand-alone.

Balanchine’s Jewels was much touted as the first program-length plotless ballet ever. The claim—good marketing fodder, like the anecdotes about the choreographer’s “fondling” a cache of gems, courtesy Van Cleef and Arpels—is tenuous. It is actually three discrete ballets—Emeralds, Rubies, and Diamonds—each independent of its sisters, as we saw subsequently, when Rubies successfully entered the repertory of other companies as a stand-alone.