Royal Danish Ballet / Kennedy Center, Washington DC / January 13-18, 2004

Frank Andersen, artistic director of the Royal Danish Ballet, has a mission. In a campaign that will climax with the 3rd Bournonville Festival in Copenhagen, June 3-11, 2005, celebrating the 200th anniversary of the great Danish choreographer’s birth, Andersen is aiming to make August Bournonville’s ballets vivid to the contemporary viewer who may not instinctively find them accessible and appealing.

Last fall, Andersen entrusted Nikolaj Hübbe (an RDB alum known best as a principal dancer in the New York City Ballet) with the responsibility for a new staging of Bournonville’s best known work, La Sylphide. I reviewed the production at its first performances in Copenhagen, where it was given with Harald Lander’s surefire crowd pleaser, Etudes. The repertory for the RDB’s recent week-long engagement at Kennedy Center, comprised this La Sylphide program and the three-act Napoli, often referred to as the Danish ballet’s calling card.

As its name suggests, Napoli is set in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius—hence, perhaps, the volcanic temperament of its characters—and mixes the exuberant mime of this population with lusty folk dancing as well as classical dancing in both its poetic and bravura modes. The ballet tells a love story—among common folk, rather than the highborn favored by much 19th-century ballet—with its only to be expected contretemps and an untypical, for the period, happy resolution. (Bournonville’s optimistic outlook is one of his charms).

As its name suggests, Napoli is set in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius—hence, perhaps, the volcanic temperament of its characters—and mixes the exuberant mime of this population with lusty folk dancing as well as classical dancing in both its poetic and bravura modes. The ballet tells a love story—among common folk, rather than the highborn favored by much 19th-century ballet—with its only to be expected contretemps and an untypical, for the period, happy resolution. (Bournonville’s optimistic outlook is one of his charms).

Napoli is filled with the choreographer’s vivid recollections of his Italian travels, recorded in his memoirs, My Theatre Life. The ballet’s first and third acts take place in a seaside market square (the hero, Gennaro, is a fisherman) that is flooded with sunlight and, on occasion, suddenly accosted by violent storms. The haunting second act occurs in the Blue Grotto of Capri, understood in the ballet as an underwater dream world (read realm of the id) only faintly illuminated by the moon. (Of this hypnotic locale, with its phosphorescent-blue water, Bournonville wrote: “How mysterious is the atmosphere, which suddenly takes away the thought of everything that has delighted—or offended—one in the outside world.”) Here Gennaro and his beloved Teresina, faithful Christians like the rest of their community, now lulled by forgetfulness of the real world with its principles and responsibilities, encounter demons of the irrational. These take the form of the powerful triton king, Golfo, and his band of naiads, whom he holds captive in a life of thoughtless (essentially erotic) pleasure. Teresina and Gennaro escape from the Blue Grotto’s temptations, which test their virtue and their free will, but only just.

Given what Andersen is trying to do—and what ballet director today is not intensively cultivating his audience?—it’s no wonder the current staging of Napoli is somewhat souped up. The opening panorama, a tour de force that presents a bustling crowd pursuing more than a dozen different agendas, is just a shade pushed—and perhaps a shade too rapid as well. Throughout the first act, the rush and the exaggeration undercut the calm, the sweetness, and the ingenuousness that have traditionally been typical of the way the RDB dances its Bournonville. Still, the staging, credited to Anne Marie Vessel Schlüter, Eva Kloborg, Dinna Bjørn, and Frank Andersen, is blessedly devoid of the newfangled “concepts” that plague many a contemporary approach to golden oldies. And the Danish dancers come through with their typical ability to take things personally, making their mime phrases “readable” and their dancing not merely a display of (often dazzling) technical accomplishment but also a communication between the dancer and dancer, as well as dancer and audience.

Several of the dancers in the two casts I saw gave extraordinary performances, and it was their interpretations, more than the production per se, that thrilled me. Tina Højlund, a perfect Teresina, is, to my mind, the most naturally talented woman in the company. Unfortunately she hasn’t had a steady stream of major roles to showcase and develop her gifts. Whether this is the company’s fault or her own or both, I can’t say, but when she’s allowed a major assignment, she can be sheer heaven.

Her dancing is everywhere fluid and graceful, given resonance by a sensuous weight. She never freeze-frames poses, like arabesques, which dancers are prone to dwell on as if they were turning their bodies into pieces of sculpture. Højlund dances through such shapes. Even more uncannily, she makes traveling steps—a high floating jeté, for instance—look like traveling, not steps, in other words, not discrete units that she has been painstakingly perfecting since she was a child, but simply an aspect of ongoing free-form locomotion.

Højlund’s acting has a similar flow and naturalness, its emotional rhythm a cousin to the rhythms of the dancing. If Teresina’s adventures seem to be happening to a real young woman, the reason lies in Højlund’s registering her feelings in every phrase. These feelings—delight, annoyance, jealousy, exasperation, tenderness, fear, sexual attraction, indecision, confusion, devout (almost desperate) faith in a protective Madonna—surge and ebb like the waves of the sea. They all belong to Teresina, they’re all expressed as parts of a single personality, but each changes the character’s personality for a moment, making her as authentic as someone you love.

Magically, none of Højlund’s dancing or acting looks as if she had been taught to do it. It looks like natural behavior. This is almost unheard of in classical ballet, and it is as pleasurable to witness as it is rare.

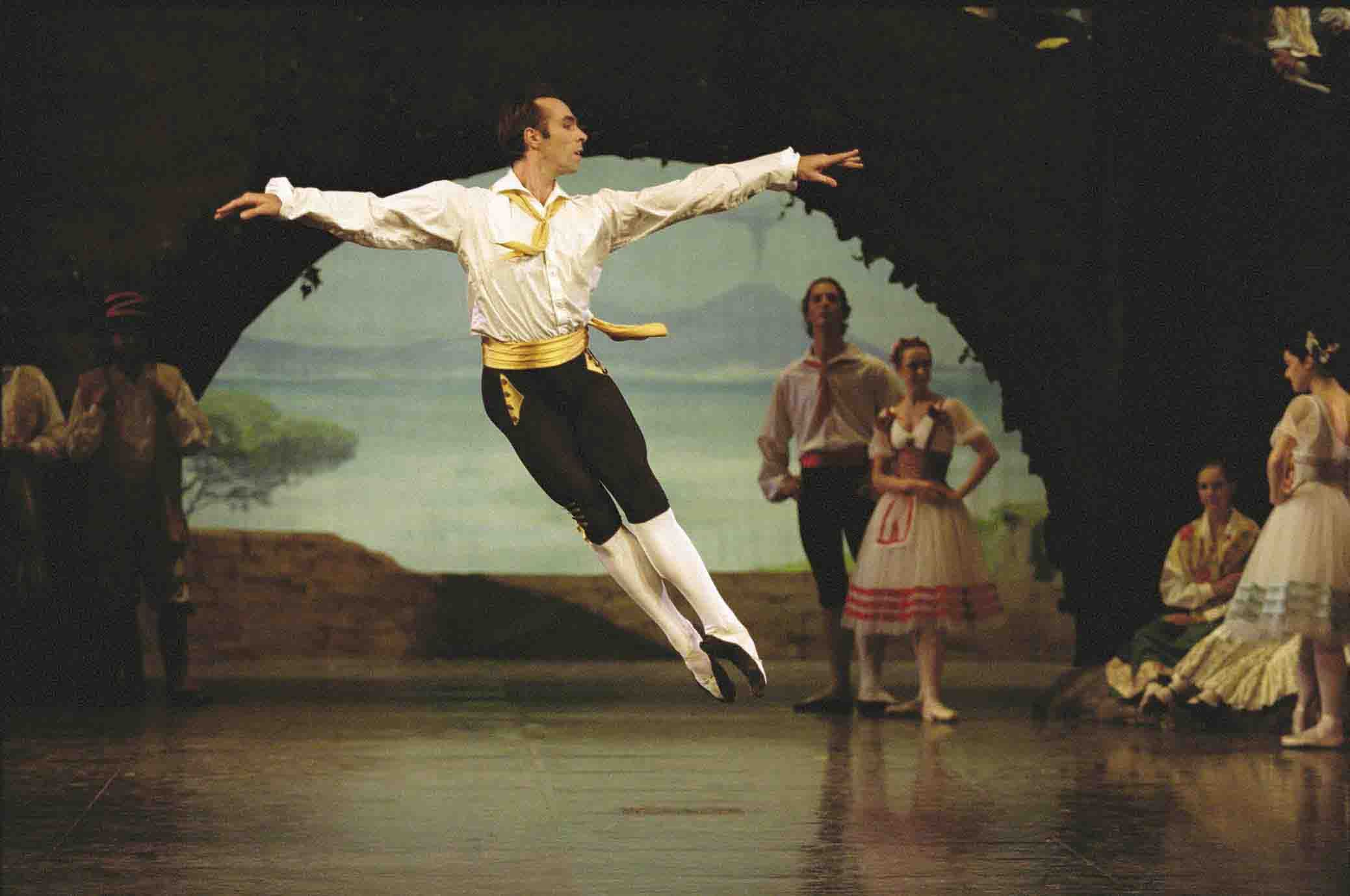

When Thomas Lund makes his entrance as Gennaro, in a huge sailing leap that charges through the assembled crowd straight down the middle of the stage, opening his arms in a wide curve as if to embrace the audience, he seems to be saying, “Here I am. Love me.” The appeal—all invitation, no ego—is impossible to resist, though Lund has neither the looks nor the build classical dancing prefers for its hero roles. Of course it would be wonderful if he had the physical glamour of gorgeous-to-die dancing Danes like Erik Bruhn, Henning Kronstam, Peter Martins, and Arne Villumsen. The gods, alas, are not always so generous.

that charges through the assembled crowd straight down the middle of the stage, opening his arms in a wide curve as if to embrace the audience, he seems to be saying, “Here I am. Love me.” The appeal—all invitation, no ego—is impossible to resist, though Lund has neither the looks nor the build classical dancing prefers for its hero roles. Of course it would be wonderful if he had the physical glamour of gorgeous-to-die dancing Danes like Erik Bruhn, Henning Kronstam, Peter Martins, and Arne Villumsen. The gods, alas, are not always so generous.

Lund earns his hero status sheerly through his dancing. Early in his career, he revealed himself to be a consummate stylist in the Bournonville technique—a master of the speed, clarity, buoyancy, and energy concealed as delight that it demands. Of late—thanks, perhaps, to the coaching he received from Nikolaj Hübbe in the new staging of La Sylphide—he has been daring to try matching that textbook perfection with a genuine, full-out expression of feeling.

Lund is not yet (may never be) completely successful in amplifying his interpretation in this way. His rendition of Gennaro’s hysterical monologue when he thinks himself responsible for Teresina’s drowning in the Blue Grotto—a passage akin to Giselle’s Mad Scene—isn’t yet fully realized or grasped as one long cry of despair rather than bite-size morsels of sorrow. But Lund’s acting has become motivated in every detail and it looks genuinely felt. With further thought, creative coaching, additional performances, and—critical for a dancer like Lund—the courage to crash the firewall of decorum, it may yet become entirely convincing.

Lis Jeppesen, who moved into character parts some years ago after an illustrious career in ballerina roles, is beginning to acquire the skills peculiar to her new mode, one of them a sense of weight. She did a swell job as Veronica, Teresina’s volatile, impassioned mom, abandoning herself to wild grief or robust joy according to the circumstances of the moment. And the DC performances indicated that she’s beginning to apply her newfound knowledge to the most challenging of her roles, the witch, Madge, in La Sylphide. Audiences, and critics especially, must learn patience. If it takes ten years to make a classical dancer, it takes the better part of a lifetime to develop a mime.

As Golfo, which can be a thankless role of standing around making power gestures, Peter Bo Bendixen cut a masterful figure. His sheer physical rightness for the role—he’s tall, dark, handsome, and admirably built—takes him a long way, of course, but he offered much more than appearance. His Golfo carefully calibrated his attempted seduction of Teresina on a scale ranging from authoritative domination to a cautious, longing gentleness, and his behavior when it’s clear he’s lost her—to Gennaro, to reality, to sunlight—bordered on the tragic.

Tommy Frishøi, one of the troupe’s senior character dancers, predictably distinguished himself as Fra Ambrosio, the monk who is the focal point in Napoli of Christianity’s belief in the power of good to overcome evil. Frishøi made you see that behind the cleric’s spiritual serenity lies a troubling doubt, and beyond that, a still-hopeful faith. Switching roles the very next day, Frishøi distinguished himself further as the Lemonade Seller, Peppo. Here, in direct contrast to his portrayal of the monk, he created a salacious figure, full of misplaced self-esteem, conniving for the sheer pleasure of making mischief. His face was an animated mask that shifted from one Daumier-like caricature to the next; his every move exuded the joy of making believe.

Frishøi’s performances are likely to be his final ones with the company in the States. He plans to retire at the end of the season—at the unreasonably early age of 63. Some of the company’s most highly evolved character dancers—who specialize in the mime roles that give a unique resonance to Bournonville’s ballets—have soldiered on, their portrayals growing ever richer and deeper, until the mandatory retirement age of 70.

When asked why hale and hearty septuagenarians were not allowed to continue their stage careers with the RDB, one of them, the late Niels Bjørn Larsen—who entered the company’s school at the age of six, served for a time as the company’s artistic director, simultaneously directing the Pantomime Theatre in Tivoli, and was an unforgettable mime—liked to explain, “We old ones have to leave to give a place to the young ones.” I can’t think of a single young one—or for that matter, middle-aged one—currently in the company who could begin to fill Frishøi’s place, who could come anywhere near the combination of realism and soul with which Frishøi infuses his characters. He is not merely irreplaceable, he’s a member of an endangered species. In the January 18th New York Times, Matthew Gurewitsch wrote, “Most full-length [ballets] reach full length by means of endless filler.” If what Frishøi does at Bournonville’s instigation is filler, balletomania is not a passion worth cultivating.

Photo credit: Martin Mydtskov Rønne: (1) Jean-Lucien Massot and (2) Thomas Lund and Tina Højlund, in August Bournonville’s Napoli

© 2004 Tobi Tobias