New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

You are a woodcutter, a swimmer, a football player, a god. —George Balanchine, instructing Lew Christensen, who danced the title role in Apollo at the ballet’s American premiere

When I was a child, I never read fairy tales. My mother disapproved of them for the underage, on the grounds that they were frightening. Perhaps she had read her Grimm in an authentic version instead of the watered-down, sweetened pap concocted for kiddies. If so, she was right about the scare factor. The only fairy tale I remember from my childhood was Snow White, courtesy Walt Disney, and it did, indeed, terrify me. What my mother preferred to ignore was the comfort that fairy tales can provide. Their reflection of primal emotions—rage and revenge, horror at the nature of the body and its functions—validates a child’s innermost feelings, reassuring him (albeit subliminally) that he is not a monster and that he is not alone.

But my mother, whose inclinations were decidedly artistic and literary, was not one to let me languish for lack of worthy reading matter. For fairy tales, she substituted classical myths, via Edith Hamilton, whose Mythology, published in 1942, is still widely read. Given the lives and impulses of the gods and goddesses, my mom’s strategy was patently illogical. But I was content with—indeed, enthralled by—the adventures of the divinities and their earthly connections. As a bonus, when I first encountered Martha Graham’s Cave of the Heart, Errand Into the Maze, and Night Journey a decade later, I knew—with a little help from Freud—just what was going on.

Hamilton’s fresh, accessible style makes the gods seem like real people, complete with human flaws and human aspirations, endowed with (doomed to, perhaps) the peculiarities of human temperament. Things happen to them and they cause things to happen—at once inevitably, because of who and what they are, and with a stunning randomness. In Hamilton’s recounting, the adventures and emotions of prodigious beings relate simply and clearly to our own smaller lives.

Balanchine’s Apollo, as the New York City Ballet danced it in the sixties, when I first laid eyes on it, was marked by a similar quality. The choreography creates events that are odd and wondrous, yet believable. A boy is born, emerges from his swaddling clothes a helpless infant, and goes from the condition of an eager, awkward child to that of young manhood just coming into its powers. The account of each stage is a matter of minutes—seconds, even—but the physical depictions are dead-on accurate.

Balanchine’s Apollo, as the New York City Ballet danced it in the sixties, when I first laid eyes on it, was marked by a similar quality. The choreography creates events that are odd and wondrous, yet believable. A boy is born, emerges from his swaddling clothes a helpless infant, and goes from the condition of an eager, awkward child to that of young manhood just coming into its powers. The account of each stage is a matter of minutes—seconds, even—but the physical depictions are dead-on accurate.

Exploring the domain that is his birthright, Apollo strums his lute and, behold, a trio of muses arrives. The strange moves of each, as she describes her assigned terrain, blend the danse d’école with things you might see in the street. The marvel is that none of this appears peculiar or archly contrived. You accept the astonishments of the ensuing proceedings—the shuffling on flat feet, the harnessing of the muses into a troika, the finger-snap shift between waking and sleeping—as being simply the way things are in this world.

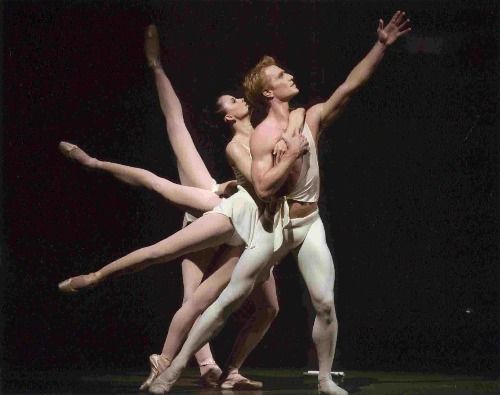

As the ballet develops, it charts Apollo’s growing confidence and authority. In his duet with Terpsichore—the mating of music and dance—it takes on aspects of sublimity that climax in the ascent to Mt. Olympus, a picture of serene ecstasy, with Apollo in the lead, one arm raised in a gesture that is part reverence, part aspiration, the muses in a faithful line behind him.

The suggestion of Balanchine’s ballet—that a god is not born fully equipped with his powers, but accedes to them through specific experience—connects the spectator to the myth. It allows him to understand Apollo’s tale as the saga of a soul finding (perhaps simply defining) its identity. In all my early viewings of Apollo—until Balanchine gave the title role to Mikhail Baryshnikov and ruthlessly cut the birth scene and the final epiphany—this atmosphere of ingenuous discovery prevailed, making the exquisite beauties of the dance all the more poignant.

At the first showing of Apollo in the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration—in the curtailed staging, alas—Nikolaj Hübbe offered an Apollo in the tradition that charts the god’s evolution, giving a performance that I consider one of the finest accounts of the role that I’ve witnessed and one of the most illustrious in his career.

A born actor as well as a richly gifted dancer, Hübbe addresses each segment of the choreography as if it were part of an ongoing story, so that every moment makes dramatic as well as plastic and musical sense. When he’s first surprised by the muses, for example, he flirts with them a little, like a college freshman delighted to encounter so many amazing girls in one spot. Gradually he becomes more authoritative as he awards each the symbol of the art she represents and then deploys them in different formations as if they were exquisitely crafted toys placed at his disposal. In his solo after the muses’ own he displays the aplomb of full manhood.

Apollo’s duet with Terpsichore, in Hübbe’s reading, becomes a grave experimental undertaking, an investigation into what the god of music can achieve or become when mated with the muse of dance. This Apollo’s approach—awed, even humble—yields increasing delights. And, as Hübbe’s interpretation proposes, increasing responsibilities that are burden as well as blessing. By the time he hears the summons to Mount Olympus, the once lighthearted, frolicsome boy has become almost tragic. With this performance, Hübbe joined my private pantheon of Apollos, which includes Jacques d’Amboise (who was present in the audience), Peter Martins, Edward Villella, and Ib Andersen.

Sorry to say, Hübbe was inadequately served by his trio of muses. Yvonne Borree (Terpsichore) was a cipher, as usual; Rachel Rutherford (Calliope) exuded her familiar loveliness and charm, but here it couldn’t cover the weakness of her attack. Jennie Somogyi (Polyhymnia), gorgeously dynamic and clear—she’s one of the most mettlesome dancers the company has ever harbored—made such an extravagant impact, the proportions of the triumvirate looked all askew. Far too often, NYCB casting seems perverse to me. I suppose I should remember that the gods have their reasons.

Postscript: I caught up on fairy tales in my own daughter’s childhood, as she avidly read her way through Andrew Lang’s marvelous collections, so aptly named for the colors of the rainbow.

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Nikolaj Hübbe and Yvonne Borree (Rachel Rutherford and Jennie Somogyi obscured) in George Balanchine’s Apollo

© 2004 Tobi Tobias