New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / January 6 – February 29, 2004

George Balanchine (Mr. Neoclassicism) did time on Broadway and in Hollywood and—always one to rise cheerfully and inventively to the particular nature of an occasion—produced some fetching work for the popular theater. As a souvenir of those ventures, the New York City Ballet’s Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration offered the Slaughter On Tenth Avenue ballet he made for On Your Toes. Jerome Robbins, NYCB’s No. 2 choreographer, may well have been in his most congenial element on Broadway. Think of his dances for West Side Story and The King and I; remember that On the Town grew from his evergreen ballet Fancy Free. So it’s not incongruous that the company should have invited Susan Stroman (Ms. Broadway) to create a program-length showpiece for NYCB to premiere on the day after Balanchine’s 100th birthday. Maybe there’s even a message (or an omen) here—“This is the first day of your second hundred years, George. Enjoy!”

Peter Martins, the NYCB’s artistic director, frankly told an interviewer for the New York Times that he wanted the Stroman work because it will sell tickets. I’m baffled by this artistic policy. Is Double Feature, as Stroman’s two-part creation is called, a fund-raising device to support the company’s more balletically inclined work? Or is it supposed to lure its audience back to the New York State Theatre for an evening of Balanchine and Robbins, Martins and Wheeldon? Using an annual six-week run of The Nutcracker—for loot and luring purposes makes sense. The Stroman venture does not. The Nutcracker, in Balanchine’s unbeatable version, is a real ballet that happens to have achieved a crazy degree of popularity. The part of the audience that goes to see it because it has become a winter- solstice ritual gets to see a classical ballet and may be tempted see others. The logical equivalent of what the audience for Double Feature sees would be another flashy, overmiked Broadway show.

Peter Martins, the NYCB’s artistic director, frankly told an interviewer for the New York Times that he wanted the Stroman work because it will sell tickets. I’m baffled by this artistic policy. Is Double Feature, as Stroman’s two-part creation is called, a fund-raising device to support the company’s more balletically inclined work? Or is it supposed to lure its audience back to the New York State Theatre for an evening of Balanchine and Robbins, Martins and Wheeldon? Using an annual six-week run of The Nutcracker—for loot and luring purposes makes sense. The Stroman venture does not. The Nutcracker, in Balanchine’s unbeatable version, is a real ballet that happens to have achieved a crazy degree of popularity. The part of the audience that goes to see it because it has become a winter- solstice ritual gets to see a classical ballet and may be tempted see others. The logical equivalent of what the audience for Double Feature sees would be another flashy, overmiked Broadway show.

As its title indicates, Double Feature is a two-part deal inspired, if that’s the word, by silent films. “The Blue Necklace” is a melodrama—about a hoofer who abandons her illegitimate infant, becomes a movie star while the babe grows to nubility (much put upon by a nasty foster mom), and reclaims her daughter once the maiden is recognized through her genetically determined gift for dancing. “Makin’ Whoopee!” is a melocomedy based on the play that inspired the movie Seven Chances, starring Buster Keaton, who could elevate slapstick to a divine plane. The plot concerns a fellow too shy to propose to his sweetheart, who eventually gets his gal after severely farcical circumstances offer him dozens of brides at once, a horde of ravening white-skirted wilis, many of them played by gentlemen of the ballet en travesti. In the hands of another choreographer, the material co-opted for Double Feature might provide opportunities for charm and good fun. Stroman, however, is largely immune to such mild enticements and opts for dazzling cleverness that is all bright, tough surface, like the finish of an exceedingly expensive car.

Knock-your-eyes-out ensemble numbers, with their escalating energy, are what Stroman does best. Granted, her big ballroom scene looks embarrassingly vacant in a repertory where “ballroom” is defined by La Valse, Liebeslieder Walzer, and Emeralds. But the chorus line of femmes in sheer black tights that opens the show and the rushing flock of wannabe brides that closes it are duly effective. The way it’s set up, though, Double Feature depends on lots of intimate vignettes to tell its tales, and it’s here that Stroman reveals her lack of a large and subtle imagination. Either she dreams in clichés or thinks her audience does and cannily gives them what she believes they want. This is an example, in little, of the way American commerce works. Ballet, being esoteric, used to be somewhat immune to it.

Stroman uses the classical ballet vocabulary—and some of its sleekest executants—like a youngster fascinated with a fabulous new toy. Oddly, though she deploys them with a lavish hand, she can’t make the steps add up to dancing. Except in the rawest ways, they serve neither plot nor character; they’re not even interestingly connected. And of course dancers trained to the highest level of balletic achievement, steeped in a repertory requiring just that, lack the gustiness—the texture, the grasp of the lowdown—that makes the Broadway gypsy unique, indeed indispensable to popular theater.

The score for Double Feature is a medley of eternally engaging songs by Irving Berlin and Walter Donaldson that are barely recognizable shorn of their lyrics and souped-up by the “original” (I’ll say!) orchestrations of Doug Besterman and Danny Troob. On the other hand, the stylized sets by Robin Wagner and the costumes by William Ivey Long—fittingly in black, white, and sepia—prove to be the best part of the show.

The large cast, including children from the School of American Ballet and a trained dog, did their best under circumstances essentially unsuited to what they are—either by nature or nurture. The pervading enthusiasm made me think of Balanchine’s comment on a another occasion: “This was not high art, of course, but we tried to do it merrily and professionally.” In “The Blue Necklace,” Kyra Nichols danced the mean mom with great (albeit misplaced) emotional sincerity, as if she’d wandered into the Tudor repertory. Damian Woetzel, as the Guy of Her Dreams, transformed his crudely pyrotechnical solo, endowing it with grace, wit, and Astairean charm. In “Makin’ Whoopee!,” Tom Gold fell short of the sweet pathos required of the hero, but Alexandra Ansanelli was delectable as his intended, though given very little to dance. Albert Evans shone in a secondary role, being an ideal crossover dancer, every bone in his body theatrical.

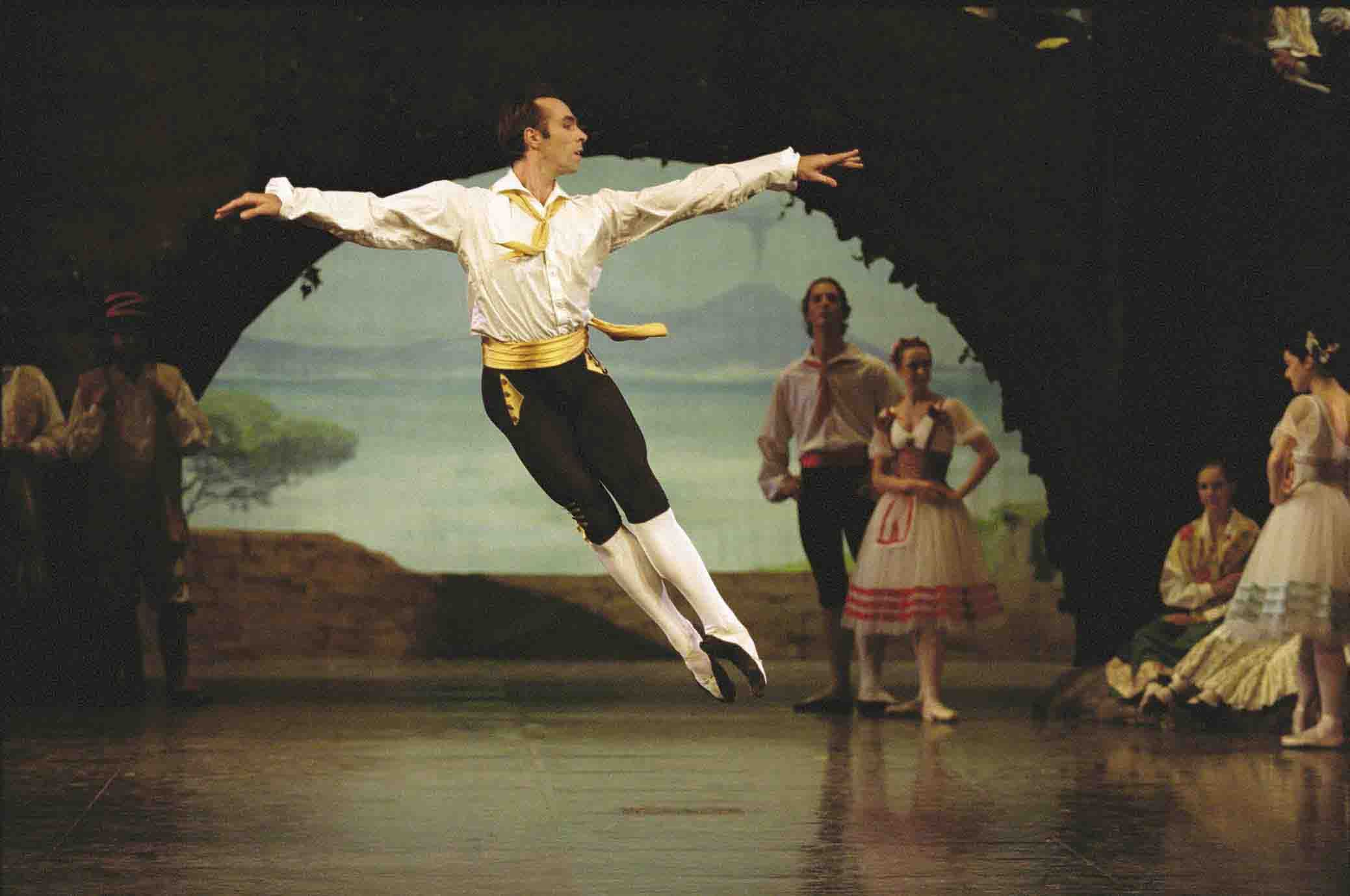

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: Tom Gold and company in “Makin’ Whoopee!” from Susan Stroman’s Double Feature

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

As its name suggests, Napoli is set in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius—hence, perhaps, the volcanic temperament of its characters—and mixes the exuberant mime of this population with lusty folk dancing as well as classical dancing in both its poetic and bravura modes. The ballet tells a love story—among common folk, rather than the highborn favored by much 19th-century ballet—with its only to be expected contretemps and an untypical, for the period, happy resolution. (Bournonville’s optimistic outlook is one of his charms).

As its name suggests, Napoli is set in the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius—hence, perhaps, the volcanic temperament of its characters—and mixes the exuberant mime of this population with lusty folk dancing as well as classical dancing in both its poetic and bravura modes. The ballet tells a love story—among common folk, rather than the highborn favored by much 19th-century ballet—with its only to be expected contretemps and an untypical, for the period, happy resolution. (Bournonville’s optimistic outlook is one of his charms). that charges through the assembled crowd straight down the middle of the stage, opening his arms in a wide curve as if to embrace the audience, he seems to be saying, “Here I am. Love me.” The appeal—all invitation, no ego—is impossible to resist, though Lund has neither the looks nor the build classical dancing prefers for its hero roles. Of course it would be wonderful if he had the physical glamour of gorgeous-to-die dancing Danes like Erik Bruhn, Henning Kronstam, Peter Martins, and Arne Villumsen. The gods, alas, are not always so generous.

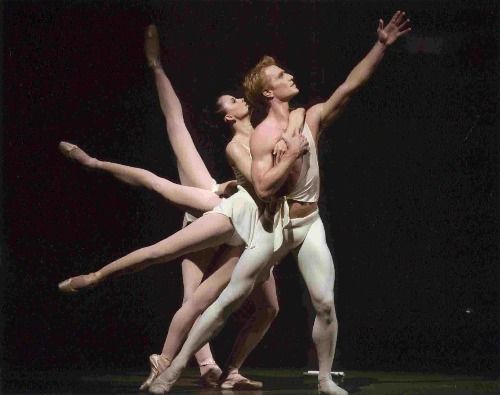

that charges through the assembled crowd straight down the middle of the stage, opening his arms in a wide curve as if to embrace the audience, he seems to be saying, “Here I am. Love me.” The appeal—all invitation, no ego—is impossible to resist, though Lund has neither the looks nor the build classical dancing prefers for its hero roles. Of course it would be wonderful if he had the physical glamour of gorgeous-to-die dancing Danes like Erik Bruhn, Henning Kronstam, Peter Martins, and Arne Villumsen. The gods, alas, are not always so generous. Balanchine’s Apollo, as the New York City Ballet danced it in the sixties, when I first laid eyes on it, was marked by a similar quality.

Balanchine’s Apollo, as the New York City Ballet danced it in the sixties, when I first laid eyes on it, was marked by a similar quality. repertoire, also fostered the dancers’ acting prowess, which has been further encouraged by latter-day additions of dramatic ballets to the company’s repertoire.

repertoire, also fostered the dancers’ acting prowess, which has been further encouraged by latter-day additions of dramatic ballets to the company’s repertoire. One might assume that the secret of the Danish school lay in a particularly ingenious or efficacious training system.

One might assume that the secret of the Danish school lay in a particularly ingenious or efficacious training system. Danish ballet’s teaching style emphasizes a

Danish ballet’s teaching style emphasizes a weekly gymnastics class–to build upper-body strength for lifting those girls over their heads and for, as an instructor put it, “joy and playfulness.”

weekly gymnastics class–to build upper-body strength for lifting those girls over their heads and for, as an instructor put it, “joy and playfulness.” they reach the age of 16.

they reach the age of 16. So what’s going on here?

So what’s going on here? The 1952 Scotch Symphony, which has just entered the Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration repertory, capitalizes on Highland local color—the valiant kilted men; the unobtainable female spirit haunting the foggy landscape; the portents of doom.

The 1952 Scotch Symphony, which has just entered the Balanchine 100 Centennial Celebration repertory, capitalizes on Highland local color—the valiant kilted men; the unobtainable female spirit haunting the foggy landscape; the portents of doom. The atmosphere Balanchine invokes—of a fairyland that can absorb human incursions and is itself fully capable of folly—is big on charm.

The atmosphere Balanchine invokes—of a fairyland that can absorb human incursions and is itself fully capable of folly—is big on charm. Daria Pavlenko, dancing Odette-Odile, was far and away the best thing about the three performances I saw (all three casts) of the Swan Lake the Kirov Ballet brought to Kennedy Center. She has, beside formidable technique, the magisterial authority of a ballerina. This is rooted in the ability to draw the audience into an imaginary universe of which she is the center.

Daria Pavlenko, dancing Odette-Odile, was far and away the best thing about the three performances I saw (all three casts) of the Swan Lake the Kirov Ballet brought to Kennedy Center. She has, beside formidable technique, the magisterial authority of a ballerina. This is rooted in the ability to draw the audience into an imaginary universe of which she is the center. Just look at the

Just look at the