Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater / City Center, NYC / December 3, 2003 – January 4, 2004

Time was, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, 45 years old this season, specialized in dances with humanitarian themes. Created largely by Ailey and a handful of other black choreographers working in the same vein, this repertory took as its subject the fight of a stalwart, resilient people, fueled by hope—a near-miraculous optimism, given their circumstances—to overcome injustice, oppression, and their corroding, often lethal, results. (In this, it echoed the liberal/socialist mindset that pervaded mid-twentieth century modern dance without regard to ethnicity.)

Corollary to this aim ran the impulse to proclaim the multi-faceted beauty of black culture by depicting its people in moments of joy, play, and celebration. Ailey’s signature piece, Revelations, choreographed in 1960, says it all. As does Donald McKayle’s deeply affecting Rainbow Round My Shoulder (1959, handsomely revived this season), which contrasts the physically and spiritually brutal life of men on a chain gang with their dreams of womankind as the source of ideal love. Succor disguised as sassy authority (mother), delicious lust (sweetheart), tenderness and constancy (wife)—all, poignantly evoked, are lost to them, just as they are lost to the women they’ve left behind, grieving.

Corollary to this aim ran the impulse to proclaim the multi-faceted beauty of black culture by depicting its people in moments of joy, play, and celebration. Ailey’s signature piece, Revelations, choreographed in 1960, says it all. As does Donald McKayle’s deeply affecting Rainbow Round My Shoulder (1959, handsomely revived this season), which contrasts the physically and spiritually brutal life of men on a chain gang with their dreams of womankind as the source of ideal love. Succor disguised as sassy authority (mother), delicious lust (sweetheart), tenderness and constancy (wife)—all, poignantly evoked, are lost to them, just as they are lost to the women they’ve left behind, grieving.

Not surprisingly, such works, which now represent the “traditional” element in the Ailey rep, contain a big ecstatic element—intensely felt if improbable visions of better times, a better world, a better fate, to be brought about by the sufferers’ faith in a power that lay beyond objective reality. Salvation, the message went, surely lay in the next life, if not in this one.

At the time of the company’s founding, part of its mission was to showcase black dancers and black choreographers, who were denied equal opportunity on the dance scene, and to speak to a black audience eager to see material that reflected its concerns and affirmed its sense of self. (It was assumed, rightly, that the non-black part of the audience—and the dance world at large—could only benefit from this strategy.)

The Ailey, now internationally popular, has seen no reason to change its position. Most of the troupe’s phenomenal dancers would identify themselves as black, as would many of its choreographers. The rising generation of American dance makers is particularly rich in black practitioners, and some of the emerging talents—Ronald K. Brown in the forefront—show tremendous promise.

Postmodernism has, of course, made its impression on the Ailey, and many of the latter-day dances added to the repertory have been abstract, shorn of specific characters, situations, and narratives. Oddly enough, though, the old themes keep surfacing in the newer works—as subtexts. The recent pieces reflect the difficult tenor of the times (though no longer in specific terms of the black experience), where alienation in a cruelly uncaring world prevails, turning the citizenry into soulless beings, even when they’re ostensibly having fun. And many of the newer dances are built on the strategy of repetition intensifying to a climax that is not merely physical release but an epiphany experienced by the soul.

Mindful of the eternal yen for novelty—on the part of the dancers as well as the audience—the Ailey unveiled four new works this season, by both black and white choreographers, and all four fall into this framework.

Jennifer Muller’s Footprints, the best of the lot, depicts a clan of pilgrims seeking a promised land or state of being indicated only by—what else?—light. They falter and fall by the wayside, then pick themselves up and persevere; they succumb to personal “issues” and internal dissention only to re-identify, through a tame but ostensibly transformative ritual, with a communal order and purpose proposed as the ultimate good. Freshly unified, the tribe proceeds on its seemingly eternal quest, though the lovely troubled maiden at the center of the action (Asha Thomas, a star in the making), hesitates and looks back, an icon of ambivalence. The piece is constructed with a scrupulous intelligence that, alas, prohibits maverick inspiration. Its originality is confined to the brilliant costumes by Karen Small, who should open a boutique immediately. Needless to say, Footprints is gorgeously danced, demonstrating that choreographic invention and depth are not as essential to pleasure as they are to art.

Jennifer Muller’s Footprints, the best of the lot, depicts a clan of pilgrims seeking a promised land or state of being indicated only by—what else?—light. They falter and fall by the wayside, then pick themselves up and persevere; they succumb to personal “issues” and internal dissention only to re-identify, through a tame but ostensibly transformative ritual, with a communal order and purpose proposed as the ultimate good. Freshly unified, the tribe proceeds on its seemingly eternal quest, though the lovely troubled maiden at the center of the action (Asha Thomas, a star in the making), hesitates and looks back, an icon of ambivalence. The piece is constructed with a scrupulous intelligence that, alas, prohibits maverick inspiration. Its originality is confined to the brilliant costumes by Karen Small, who should open a boutique immediately. Needless to say, Footprints is gorgeously danced, demonstrating that choreographic invention and depth are not as essential to pleasure as they are to art.

The score commissioned from John Mackey for Robert Battle’s Juba is highly percussive and so is the choreography, based on the premise—investigated variously by the whirling dervishes, Mary Wigman, Laura Dean, and Lucinda Childs—that incessant repetition ferries you to a higher plane of consciousness (or whatever). Battle, who has a flair for the effective gimmick, gives us a quartet sealed into a tight matrix of togetherness, beating feet into floor and fists into thighs. The never-let-up thudding flicks the audience’s response switch to “On,” encouraging the view that the anonymous, relentlessly animated figures are not trapped, but actually enjoying themselves.

With Bounty Verses—set to music ripped from strange bedfellows like Bach, Steve Reich, and Kurt Cobain—Dwight Rhoden has created his usual knock-‘em-dead showpiece. Its frenetic disco atmosphere reflects the hectic nature of urban lives lived, as they are today, at unremitting high intensity, with its consequent mindlessness. In the world Rhoden represents, nothing—not a passage of dancing, let alone an affair of the heart—can be sustained. The piece is guaranteed to raise your stress level but, mercifully, it’s an example of time out of mind tonight, forgotten tomorrow.

Alonzo King’s unfathomable Heart Song mates a vocabulary co-opted from classical ballet with songs of Arabia and chichi stylistic devices typical of dance in the 1920s. Is King borrowing ironically from Europe’s patronizing view of black dancers—as creatures fascinating in their otherness—prevalent at that time? Heart Song is too unfocused to tell, but I’ve filed it in the exoticism category for the moment.

I doubt that any of these works will last long in the repertory; there’s no reason why they should. Next year the company might do well to relinquish one of its New Ballet slots to a resurrection from its Warehouse of Golden Oldies. Perhaps, since Donald McKayle restaged his Rainbow so vividly, a revival of his District Storyville is now in order, not merely for its historical value, not just because it would make a telling show, but also because it has the Ailey’s interests at heart.

Photo credits:

1. Andrew Eccles: Glenn A. Sims and Matthew Rushing in Donald McKayle’s Rainbow Round My Shoulder

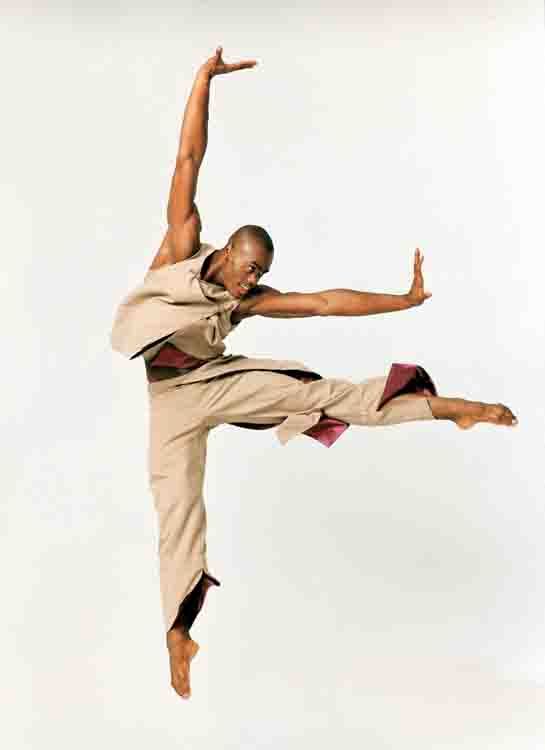

2. Andrew Eccles: Jamar Roberts in Jennifer Muller’s Footprints

© 2003 Tobi Tobias

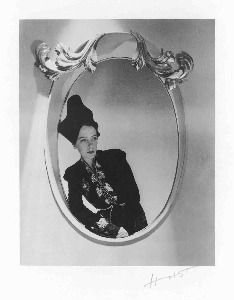

If Schiaparelli was not a beauty, neither was she a belle-laide, as is sometimes claimed.

If Schiaparelli was not a beauty, neither was she a belle-laide, as is sometimes claimed.

Dalí was incontestably Schiaparelli’s primary Surrealist influence (and collaborator).

Dalí was incontestably Schiaparelli’s primary Surrealist influence (and collaborator). Schiaparelli also linked up with the sweet ironies of Cocteau’s poetic vision, translating a pair of his continuous-line drawings into embroidered images on apparel.

Schiaparelli also linked up with the sweet ironies of Cocteau’s poetic vision, translating a pair of his continuous-line drawings into embroidered images on apparel. glamour, creating a kind of chic noir.

glamour, creating a kind of chic noir. Accessories were central, not peripheral, to Schiaparelli’s work.

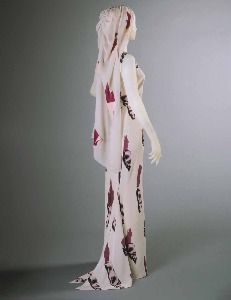

Accessories were central, not peripheral, to Schiaparelli’s work. During World War II, Schiaparelli took shelter in the States, where she refused to design, manifesting her solidarity with her French colleagues, stymied in their work by the Nazis.

During World War II, Schiaparelli took shelter in the States, where she refused to design, manifesting her solidarity with her French colleagues, stymied in their work by the Nazis. Doug Varone boldly (recklessly, if you will) co-opted Stravinsky’s Firebird score for his contribution, The Beating of Wings, but apart from some references to the old Russian tale that the composer drew on and the ballets subsequently choreographed to the music (Fokine’s the first and finest among them), he essentially made a Varonesque work.

Doug Varone boldly (recklessly, if you will) co-opted Stravinsky’s Firebird score for his contribution, The Beating of Wings, but apart from some references to the old Russian tale that the composer drew on and the ballets subsequently choreographed to the music (Fokine’s the first and finest among them), he essentially made a Varonesque work.