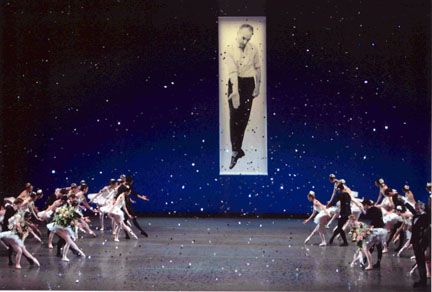

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, Lincoln Center, NYC / November 25, 2003

The George Balanchine Foundation: Videotaping of Violette Verdy coaching George Balanchine’s Emeralds / Samuel B. and David Rose Building, Lincoln Center, NYC / October 27, 2003

Works & Process: Balanchine’s Lost Choreography / Guggenheim Museum / November 16 & 17, 2003

January 22, 2004 marks the 100th anniversary of George Balanchine’s birth. The celebratory “year” that is wrapped around this propitious date follows the art and social worlds’ custom of beginning in the fall and extending through the following spring. It has been and will continue to be filled with activities centering on the man who shaped twentieth-century ballet according to his singular vision. No end of exhibitions, archival undertakings, film and video screenings, symposiums, and – most important – productions of the ballets worldwide are calling attention to Balanchine’s genius. (A continually updated schedule of the happenings is available at http://www.balanchine.org/05/archive/2003cent3.html.) There will even be a George Balanchine postage stamp, Mr. B sharing an American Choreographers commemorative with Miss Graham, Miss De Mille, and Mr. Ailey. (Leave it to the U.S. Postal Service to indicate the marginality of dance in our culture by determining that none of its practitioners deserves solo homage!)

January 22, 2004 marks the 100th anniversary of George Balanchine’s birth. The celebratory “year” that is wrapped around this propitious date follows the art and social worlds’ custom of beginning in the fall and extending through the following spring. It has been and will continue to be filled with activities centering on the man who shaped twentieth-century ballet according to his singular vision. No end of exhibitions, archival undertakings, film and video screenings, symposiums, and – most important – productions of the ballets worldwide are calling attention to Balanchine’s genius. (A continually updated schedule of the happenings is available at http://www.balanchine.org/05/archive/2003cent3.html.) There will even be a George Balanchine postage stamp, Mr. B sharing an American Choreographers commemorative with Miss Graham, Miss De Mille, and Mr. Ailey. (Leave it to the U.S. Postal Service to indicate the marginality of dance in our culture by determining that none of its practitioners deserves solo homage!)

Despite this all-over-the-map activity or, perhaps, stimulated by it, one still looks to the New York City Ballet, Balanchine’s home base during the major part of his career, for the truest performances of his canon. In the course of its extended winter and spring seasons at the New York State Theater (aka the house built for Balanchine), amid a flurry of peripheral activities, the company promises to perform 54 of the choreographer’s works, 42 of them created for the NYCB. “Balanchine 100: The Centennial Celebration,” as the project is called, will be further extended by national and international engagements. (For details, go to http://www.nycballet.com/nycballet/homepage.asp and click on the “Balanchine 100” poster.) The incomparably rich repertory will be organized into easily identified categories: “Heritage” this winter, “Vision” in the spring, with subsets grouping the ballets according to the composers of their scores. While this corralling and labeling is no doubt necessary for marketing purposes, what ultimately matters is the quality of the productions themselves.

On November 25, the company offered a single night of repertory, preceding the endless weeks of “The Nutcracker” that help pay its bills. The event temptingly offered itself as a litmus test, indicating how the Balanchine legacy is faring in the place where its treatment counts most.

The program consisted of “Serenade,” the first ballet Balanchine made in America and one of the most inventive, beautiful, and moving he ever made; “Bugaku,” a top contender in the choreographer’s “strange and marvelous” mode; and that icon of neoclassicism, “Symphony in C.” The performance of this last ballet was the most commendable – for its rendering of crisp clean dazzle throughout the ranks. And overall the evening demonstrated that the New York City Ballet remains by far the most eminent custodian of Balanchine’s work, a force schooled to dance with a precision and musicality that still look like news. Yet the very fact that this needs to be said indicates some flaws in the picture.

I believe that a good part of the problem is that no one is as deeply and unremittingly concerned as Balanchine once was with the nature of individual dancers’ specific personas and gifts. He was acutely conscious of such matters when he created his ballets and when he recast them over the years as well. He developed his dancers not merely in the classroom but through the roles he gave them. Nowadays, casting often seems thoughtless. Kyra Nichols, Yvonne Bourree, and Sofiane Sylve, dancing the three leading women in “Serenade,” made a disconcertingly odd trio; they hardly seemed to be in the same ballet. Bourree looks weak and ineffectual, while Sylve is robustly athletic but not yet able to give her physical force a dramatic dimension. Nichols, on the other hand, in the last stage of her performing career, technically muted though still gloriously pure, has become increasingly luminous emotionally. She alone seemed to know that something is going on in “Serenade” besides steps.

The casting of Darci Kistler in “Bugaku” was well-nigh disastrous. At this point in her dancing life, what with the erosions of injury and age, she’s not equal to the technical demands of the piece. Even more significantly, the peculiar stylized Japanese-court eroticism of the piece is utterly uncongenial to her fresh-faced American girl style and temperament. Her formidable imagination carried her a long way, as usual, but not, I think, in the direction Balanchine was going here. But then the whole piece has been shorn of its original atmosphere, and without the sense of exotic ritual and mystery that once informed it, it seems, by turns, pointless and vulgar.

In all three ballets, actually, most of the principals’ dancing looked badly in need of coaching, and the ballets themselves lacked a sense of vision behind them. It’s the rare dancer who can figure things out entirely on his or her own. And choreography is not just an objective text of moves; it requires interpretation. This is where the custodians of history come in. Once a choreographer is no longer available to revivify his or her works, dancers who knew them best can help to recreate them and ensure their ongoing viability.

Since Balanchine’s death in 1983, however, the NYCB, essentially under Peter Martins’s direction, has been reluctant to let Balanchine’s celebrated galaxy of ballerinas (and important male dancers as well) participate in coaching its productions of the ballets to whose creation or rich ongoing life they contributed so memorably. Artists of the caliber of Suzanne Farrell and Violette Verdy, who effectively do such work for other American companies (Farrell now has her own) – and abroad from Paris to St. Petersburg – are shut out at home, Balanchine’s home.

The George Balanchine Foundation has instituted two archival video projects that demonstrate what can be accomplished when the past is retrieved and revered. Launched in 1994, the Interpreters Archive, according to its statement of purpose, “documents the coaching of Balanchine roles from those on whom the roles were created in order to preserve original choreographic intent.” The recordings of Allegra Kent, the most haunting of Balanchine’s ballerinas, coaching “Bugaku” and “La Sonnambula” alone prove the worth of close personal instruction from dancers set in motion by the choreographer himself.

I had the privilege recently of observing the day-long taping of Violette Verdy coaching dancers from the NYCB in the solo and pas de deux (assisted here by her partner, Conrad Ludlow) that she originated in the “Emeralds” section of “Jewels.” As Verdy worked – with her usual brisk energy, seemingly concentrating on practicalities of steps and rhythms – she restored to the ballet the full force of its signature texture and perfume. At one point she attempted to elicit from the very young Carla Körbes, an exceedingly promising NYCB talent, the quality that she, Verdy, brought to the arm and hand gesture that is a key motif in the solo. Demonstrating as she spoke, Verdy suggested that she think of the hand as a long, lovely feather with which the girl caresses her cheek. Though Körbes has never even seen the ballet live, she’s an apt vessel for received wisdom, and she got it in one. The phrase she had first reproduced mechanically – to perfection – was now transmuted into an emanation.

Edited, the videotapes in this project are made available to research libraries worldwide. In other words, they have arrived at, and will continue coming to, a source near (or accessible to) you. So you can see for yourself, without taking my fallible word for it, elements of Balanchine’s vision no longer present in today’s productions of a given ballet, qualities that, if attended to, could add significantly to the resonance of current stagings.

Another Balanchine Foundation enterprise, the Archive of Lost Choreography, according to the dry, modest reportage of the organization, “retrieves fragments of Balanchine works no longer performed.” This too, is essentially a videotape project – material to be accessed at a library – but its latest incarnation was vividly supplemented with live public performance. In the estimable Works & Process series at the Guggenheim Museum, Maria Tallchief (foremost among Balanchine’s early American muses) and Frederic Franklin (profoundly influenced by Balanchine at the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo) worked with young NYCB dancers on versions of “Le Baiser de la Fée” and “Mozartiana” that Balanchine later discarded in favor of his new conceptions of their respective Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky scores. Ironically, the old, recouped choreography offered the felicitous shock of the new, even to a veteran viewer like me. Imagine, here was the very thing we never expected to see again, a new Balanchine ballet (well, only a passage from one, but still . . .).

The evening was enhanced by film fragments of the material being rescued from oblivion, danced inimitably more than a half century ago by Tallchief, Franklin, and Alexandra Danilova. It was also punctuated by interview segments with the articulate senior artists on hand, conducted by the dance scholar (and former NYCB dancer) Nancy Reynolds, who masterminds both the projects discussed here. At one point Reynolds proposed, rhetorically, of the original “Baiser,” “So it’s a lost ballet,” to which Tallchief snapped back, “Not while Freddie and I are around.”

Franklin, sharp and spry as they come, active as a stager and coach in many venues, blessed with a sanguine personality that makes him the most accessible of instructors, also has a birthday coming up. He’ll be 90 in June. What is the dance world waiting for? It is now twenty years since Balanchine’s death. Let’s assume that Balanchine’s home team, for its own good or not so good reasons, chooses to forego the input of Balanchine’s illustrious associates. Surely other companies can benefit from their counsel – indeed, from their very presence. What is now done to some extent on an ad hoc basis is crying out to be organized and subsidized. What more suitable birthday tribute to Balanchine could there be?

Photo credit: Paul Kolnik: New York City Ballet bows to Balanchine, November 25, 2003

© 2003 Tobi Tobias