George Piper Dances / Joyce Theater, NYC / November 4-9, 2003

George Piper Dances, at the Joyce through November 9, is named for the conjoined moniker-in-art of Michael (middle name: George) Nunn and William (Piper) Trevitt. The pair of Brits with charm to spare and an unexpected taste for austere, ostensibly cerebral choreography are also known as the Ballet Boyz, after the title of a popular T.V. series they did on dancers’ backstage and offstage lives (a subject of enduring public curiosity).

Brief chronology: Pals at the Royal Ballet’s august academy, Michael and Billy (as he prefers to be called) went on together to put in a dozen years with the parent company, rising out of the corps to the rank of First Soloist and Principal respectively. Gradually they found their jobs to be same old same old, and their discontent was exacerbated by internal roiling in the grand old institution. So off they went to do their own thing, to “make it new,” as feisty artists have longed to do since modern times began. A venture called K Ballet in Japan turned out to be insufficiently high art for them, hence George Piper, founded in 2001.

Brief chronology: Pals at the Royal Ballet’s august academy, Michael and Billy (as he prefers to be called) went on together to put in a dozen years with the parent company, rising out of the corps to the rank of First Soloist and Principal respectively. Gradually they found their jobs to be same old same old, and their discontent was exacerbated by internal roiling in the grand old institution. So off they went to do their own thing, to “make it new,” as feisty artists have longed to do since modern times began. A venture called K Ballet in Japan turned out to be insufficiently high art for them, hence George Piper, founded in 2001.

Last spring, Nunn and Trevitt worked up Critics’ Choice *****, a program of short pieces by five contemporary choreographers they admired intercut with videotaped documentation of the works’ creation—the idea being to show how each choreographer operates. The Joyce program continued the policy of offsetting the live dance numbers with hyperactive video footage that may not reveal all that much about the creative process but vividly presents the Ballet Boyz as regular guys, modest and dedicated to their work, at the same time wry and irreverent—in other words, apt candidates for popularity.

Five dancers performed the Joyce bill of three strenuous works: Trevitt and Nunn, along with Hubert Essakow (another ex-Royal) and a pair of killer-chic women from elsewhere, Oxana Panchenko and Monica Zamora. The dances were uniformly abstract, with long monotonal stretches and minimal affect—a programming flaw guaranteed to make the most resolute modernist sensibility succumb to a momentary longing for a story, a recognizable character with a self-evident problem, even a swan.

William Forsythe’s 1984 Steptext, which opened the show, stated the adamantly non-objective aesthetic that was to prevail. Set to shards of a Bach chaconne, it glamorizes ferocious mean-mindedness. The dancers labor arduously in isolation, handsome and fraught, or in couple work that masks deft physical cooperation with a confrontational attitude. A repeated motif consists of raising the arms, right-angled at the elbow, and beating the fists together. Someone—the other guy, the whole goddamn world—is angling for a fight. Much of the action suggests the disjunctive dancing that takes place in rehearsal—isolated bits and pieces that cut off abruptly, impatient waits for musical cues, frustrating passages of partnering that don’t cohere. Of course, if you’ve a mind to, you can take this stuff as a metaphor for life itself. Or, if you prefer, you can fret over the way Forsythe’s women get manhandled, despite their own tough hostility. At one point, the growing menace of silence is broken by the music, whereupon the stage lights are extinguished, and the audience sits watching a dance it can’t see.

Christopher Wheeldon, Resident Choreographer at the New York City Ballet and the rising youngish hope of the ballet community, provided the show’s most attractive piece, Mesmerics, expanded to quintet status from its earlier trio form. Set to a kaleidoscope of Philip Glass music, the dance centers on an elaborate, languorous twining of long, svelte limbs, often with the dancers splayed out on the floor. They might be underwater swimmers, even dream figures enacting a wordless romance, except for the fact that brute strength clearly underlies their grace. Erect, the dancers travel on lateral paths, arms wheeling occasionally, as if as if tracing brief moments of turbulence on an infinite timeline.

As always with Wheeldon, everything that happens is beautifully contrived, carefully placed in a scrupulous architectural structure. The piece maintains its look with a consistency you’ve got to admire, yet this thoroughgoing adherence to pattern suggests an unfortunate cousinship with sleek interior decoration. Although the piece eventually achieves some mounting intensity, little happens that’s unexpected, nothing occurs to disturb the universe as the choreographer first proposed it. I admire Wheeldon’s skill, but I distrust his impulse. To me, all his exquisitely crafted dances seem to be fashioned from the outside in. They may look terrific, but they fail to accomplish one of art’s first duties—shaking up the mind or the heart.

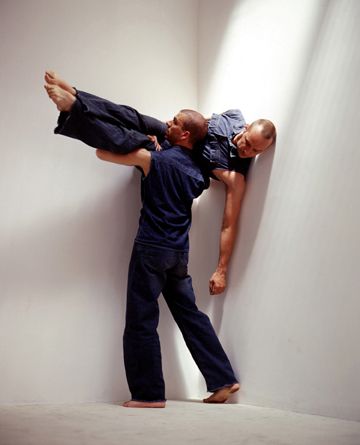

A duet for Nunn and Trevitt, seemingly based on the dancers’ close friendship, Russell Maliphant’s Torsion relies on that oh-so-yesteryear tactic of combining movement genres that (1) have little in common and (2) are absent from the curriculum of traditional dance academies. Contact improvisation dominates here, seconded by devices from capoeira, hip-hop, yoga et al. The friendship business goes on forever, oddly blue in tone, as if togetherness were impossible to maintain or reclaim, and dismayingly dependent on the partners’ alternately outstretched and clasped hands. And here we were thinking, from the upbeat sophomoric humor of those videos, that the boyz were going great, their bond so firm and cheerful. If the audience is not to confuse life and art, then George Piper should not employ strategies encouraging it to do so.

Things to know, if you believe the folks who say that GPD represents the future of classical ballet, an art they claim is dying on its feet: (1) Classical ballet is a technique that can serve anywhere. Wheeldon is essentially operating in it, using newfangled stuff largely as ornament. Forsythe seizes parts of it as his heritage then proceeds to conduct an ongoing argument with it, sometimes with inventive results. Even Maliphant, with his polyglot, anti-Establishment movement vocabulary, falls back on it when he thinks you’re not looking. (2) Classical ballet is also an art form that, like opera, is most itself when it can operate with a goodly number of performers in a sizeable house. The court ballets of Louis XIV’s era, the ballets of Petipa, and most of Balanchine’s and Ashton’s memorable works depend on generous dimension and on a hierarchy that distinguishes among principal, soloist, and ensemble ranks for choreographic purposes. Corps de ballet, remember, may be translated as “body of the ballet” and the power of a group moving in unison is not to be underestimated (as military parades prove). To be sure, there are unforgettable chamber-scale ballets (think of Ashton’s Monotones), but a repertory consisting solely of small numbers, even if they’re gems, offers its audience a very limited experience.

Another thing to know: Even with the purest of intentions—for the sake of argument, let’s credit the Boyz with these—it may be impossible to engage a broad audience with highbrow “advanced” choreography. Mikhail Baryshnikov had a splendid go at it for some years with his White Oak Dance Project on the strength of his name and his gifts as a dancer even after age and injury eroded the virtuoso aspect of his powers. But, to paraphrase Lincoln Kirstein—who masterminded Balanchine’s career, to say nothing of the development of the New York City Ballet as an institution—ballet is simply not destined to interest as many people as football does. There are indeed ballet moms as well as soccer moms, but a huge difference remains in their numbers. While George Piper Dances is fine and dandy, Nunn and Trevitt might do well to concentrate their considerable talents and energies on expanding the scope of their repertoire instead of trying to make themselves household words.

Photo credit: Hugo Glendinning: Michael Nunn and William Trevitt in Russell Maliphant’s Torsion

© 2003 Tobi Tobias