“Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration” / Film Society of Lincoln Center, Walter Reade Theater, NYC / October 4 – November 5, 2003

Dance aficionados as well as film connoisseurs will be drawn to the Walter Reade Theater for the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s “Yasujiro Ozu: A Centennial Celebration,” October 4 – November 5. The lure for the dance crowd? The iconic director’s insight into movement and his rendition – always sensitive and frequently sublime – of feelings that lie past the reach of words.

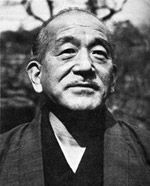

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing – an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period – extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties – once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Those just glancingly acquainted with the work of Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963), as well as his committed fans, characterize the Japanese film director as the master of non-action. At heart, his films concern themselves with being, not doing – an attribute of the Zen thinking with which his outlook is allied. Ozu embodied the quality of transcendent stillness most perfectly in his middle period – extending from the mid-thirties to the mid-fifties – once he had, somewhat reluctantly, adopted sound, but before he had, with equal reluctance, succumbed to color. (His earliest films, enchanting silents, are often highly animated.)

Creating a peerless series of black and white “talkies” over two decades, Ozu probed the extraordinary ways in which limitation can serve to reveal the intangible (and most significant) aspects of existence, focusing the attention on essences rather than events. One of his most apparent means was stasis: minimal body and facial movement for the actors (emoting was thus precluded) and a fixed position for the camera, which then regarded the material before it like the unwavering eye of God. What is most curious about this denial of motion is the tremendous importance motion assumes when it does occur. Like that of very different masters – Balanchine, Ashton, and Tudor – Ozu’s “choreography” creates epiphanies by manifesting intense, unarticulated feeling through physical action. And it does so in remarkably varied ways.

In the 1953 Tokyo Story, as is typical of the mature Ozu, plot has become as fragile and translucent as a silver-penny petal. The film is dominated by a theme that obsessed Ozu throughout his career: the nature of human experience as it is expressed in the relationships between parents and their grown children.

An aging pair make a momentous visit to the big city where they find their adult offspring largely too preoccupied with their own concerns to give them the loving respect and attention one might assume to be a parent’s due. Resigned to their disappointment, they journey home, whereupon the mother succumbs to a stroke and lies unconscious on her deathbed. Ironically too late, the children gather in attendance around her pallet. Although charged with feeling, the scene – with the inert body at its center – is utterly quiet and self-contained. It’s almost a still life, the actors and the camera are physically so subdued.

The younger brother arrives after the others, explaining he’d been away on business when the summons came. He’s literally too late; while the camera gazed outward to the town, the sky, the river – the larger, sentient universe – the mother expired. By custom, her face is covered with a square of white cloth. “Look at her,” an elder sibling urges the latecomer, “she looks so peaceful.” The son moves to lift the cloth and, with typical Ozuian obliqueness, the camera – its rhythm as unforced and acutely timed as a sleeping child’s breath – cuts away. So we don’t see what the son sees – the mother’s placid face in death. We don’t need to. It already exists in our imagination. Nor do we see the son’s face; Ozu would consider even such a minor bit of melodrama tactless both emotionally and aesthetically. Instead, he slews the camera around to the other figures’ response, a kind of visual harmony to the unrecorded event. Kneeling, passive as hills, gazing down at their hands, they lift their heads to witness their brother’s sight, then, as one, incline slightly from the waist and neck, instinctively bowing to the sacredness of the moment.

This passage from Tokyo Story epitomizes the beauty and deftness with which Ozu makes his primary emotional point through a single move – the bow – in an environment of physical and emotional quiescence. In The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice (1952), the climactic scene is based upon a journey – geographically minute and on domestic turf, poetically immense and structured as formally as a classical ballet. An estranged husband and wife, having reached the point of reconciliation, penetrate by stages into the core of their home, the kitchen. A modest room at the back of the dwelling, down several stairs, it fulfills a basic human need – hunger – yet this long-wed couple hardly knows where it is. (The erotic parallel is obvious, though it’s not in Ozu’s nature to belabor it.)

The husband is a simple man – blunt, good-hearted, tenaciously unaffected. His taste is for the common, unpretentious things of his background. They fit him, he explains at one point, later amplifying his observation: “It’s how a married life should be.” Superficially sophisticated, disappointed in the dullness of their union, his wife has rebuffed him for his lack of refinement. Now, having learned through pain to understand and appreciate each other, they celebrate by going in search of a midnight bowl of rice doused in green tea – a peasant meal, typically consumed with slurping relish.

The kitchen is hidden, almost unknown, territory to this comfortably-off pair, but to preserve the intimacy of their newfound accord, they choose not to summon their sleeping maid to serve them. Side by side, touching each other so lightly and unemphatically, their physical contact is barely visible, they slide back the wall panel of their living room, pass through a narrow, dimly lit corridor, slide open yet another panel, and illuminate a primitive hanging lamp that discloses the humble kitchen so mysterious to them. Together, they prepare their repast – he gently draws back her kimono sleeve as she washes her hands – and return by the same route, soft-edged shadows on the translucent panels they shut behind them.

Their journey – with its unstressed sexual parallel – is one of venturing by degrees, of lifting veils and entering uncharted passageways. As it progresses, the bourgeois environment and the bourgeois situation dissolve into evocations of legendary quests: Orpheus descending into the underworld in search of Eurydice, the prince of Perrault’s Sleeping Beauty crossing the barriers that separate him from his heart’s desire.

Late Spring, made in 1949 and perhaps Ozu’s most exquisite achievement, uses an image of nature in motion to express human feeling. The tale – again, one that Ozu reiterated as if he could never be done with the issue – concerns a widower who realizes he must release his beloved and devoted daughter from tending him into a life of her own. She’s reluctant to leave the serene, secure shelter of her girlhood, so he deceives her into thinking she must marry because he wants to remarry. The idea of her father’s entering into a sexual alliance after her mother’s death revolts the young woman. Matters come to a crisis at a Noh performance, when the daughter sees her father exchange gazes with the lovely widow who will presumably appropriate her place.

This being an Ozu film, not a word is spoken directly about the matter, but the daughter’s swiftly mounting feelings of anger and desolation are clear, almost unbearable in their repressed intensity. The theater scene ends and, as is Ozu’s custom in shifting locale, a landscape shot is inserted. Technically, it’s a transitional device; aesthetically, it’s a container for human emotion so dense and many-faceted it can’t be particularized. Several such shots, earlier in this film, showed a few thin, barren tree trunks. Now Ozu’s camera looks up at a flourishing tree, proudly set against the blank sky. At the peak of its maturity, the tree is wide and thickly branched, in full leaf. A wind blows through it, making its foliage dance in the sunlight, as if to emphasize its vitality, and its already luxuriant expanse seems to inflate, like a lung. The tree – whether you take it to be just a tree or a symbol of unquenchable, continuing life – is breathing. The breath is the breath of immanence.

© 2003 Tobi Tobias