This article originally appeared in Tutu Revue.

Every spring, America’s two grandest classical ballet companies play a long annual season — most of May and June — opposite each other at Lincoln Center. American Ballet Theatre holds forth at the Metropolitan Opera House, while the New York City Ballet dances at the New York State Theater. The repertories of the two troupes are dazzling, in terms of both quantity and quality. NYCB is the repository of the work of George Balanchine, the giant of twentieth-century choreographers. ABT features opulent versions of nineteenth-century storybook classics like “Swan Lake” and latter-day imitations of the genre. Both companies boast additional treasures — works by dance makers like Michael Fokine, Antony Tudor, Jerome Robbins, Twyla Tharp, and Mark Morris, who are sure candidates for the history books, as well as pieces by the most adept of the other contenders, the NYCB’s Christopher Wheeldon standing just now at the head of that class.

Similarly, the dancing — together, the troupes employ some 168 performers — is of the very highest caliber. Each ensemble member can be said to represent hundreds of also-rans; he or she is, typically, the prize pupil deemed worthy of export to the mecca. Yet something essential is missing. Apart from a few senior artists whose powers have been waning for some time, neither NYCB nor ABT harbors anything you could genuinely call a ballerina. It may very well be that the species is nearly extinct.

Should we mourn it? I think so. “Ballet is woman,” Balanchine declared, and despite sensational guys like Gaetano Vestris and his son Auguste, known ‘way back when as “gods of the dance,” and, subsequently, Vaslav Nijinsky, Erik Bruhn, Edward Villella, Rudolf Nureyev, Anthony Dowell and Mikhail Baryshnikov — to say nothing of the cluster of kamikaze virtuosi currently exciting the ABT audience — Balanchine had a point. It may take a female dancer, magnified exponentially until she seems more goddess than human, to make the proceedings on the classical-dance stage cohere and reverberate to the point of moving the viewer to ecstasy. (This sense of life amplified and glorified is what transforms otherwise reasonably normal folks into balletomanes — the ballet-mad.) But what, exactly, is this creature we term a ballerina?

Marie Taglioni

One way to define her is to call to mind unforgettable examples of the breed. The ballerina as we conceive of her today can be said to have emerged in the Romantic era. In the 1830s the evolution of the soft dancing slipper to the reinforced pointe shoe, which permitted its wearer to perch on the very tip of her toes, helped to turn her into an otherworldly being, beyond the dullness of pedestrian existence. The enchanting engravings of the period exaggerated the look, so that the apparition the lady typically portrayed (the Sylphide, Giselle in her Wili guise) seemed poised on the business end of a needle, ready to be wafted into space by the merest breeze or admirer’s sigh.

Fanny Elssler

The reigning idols of that period doubled their potency by emphasizing their contrasting temperaments. Marie Taglioni was chaste and ethereal, the “pagan” Fanny Elssler, a sexy fireball.

Anna Pavlova

Anna Pavlova epitomized the ideal of the ballerina in the early twentieth century. Like Balanchine a product of St. Petersburg’s Kirov Ballet, Pavlova was an emblem of pure spirit — now tragic, now possessed by a volatile joy. Her uncanny aptitude for seizing the audience’s imagination (with the help of astute publicity) turned her into an icon. Even her death was mythologized. Legend has it that, gravely ill with pleurisy aggravated by her insistence on constant touring under grueling conditions, she died calling for her tutu so that she could give her next performance. What better way to seduce the public than immolating oneself upon the altar of art?

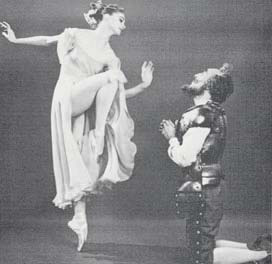

Margot Fonteyn

The ballerina of the mid-twentieth century — the one who shaped the taste of devotees born before the second World War — was the British Margot Fonteyn, whose career had an unusually extended life thanks to the charismatic partnership she formed with the young Nureyev upon his dramatic emigration from Russia to the West. Fonteyn was the paradigm of musicality, lyricism, purity of line in repose, harmony in motion. Her luminousness, which was warm rather than (like Pavlova’s) above it all, was irresistible. Dance fans in the first third of the twentieth century worshipped Pavlova; their counterparts in the forties, fifties, and sixties loved Fonteyn.

Farrell and Balanchine

One more generation down the road, just at the vanishing point of the ballerina’s dominance of the classical-dance stage, we have the incomparable adagio dancer Suzanne Farrell, Balanchine’s last and probably most significant muse, a unique mix of the erotic and the sublime. Even these few examples suggest the diversity possible within the ballerina category; the shared quality, I’d venture, though cynics will ridicule the idea, is a gift for making dreams incarnate.

Galina Ulanova

Another way to describe the ballerina is to examine her attributes. They’re a matter of both body and soul. Good-to-outstanding anatomy and technique can be considered prerequisites. (The preferred figure-type and the expected level of virtuosity have, of course, varied with the times.) Actually, some of the most memorable ballerinas have been deficient in one department or the other. Fonteyn, who happened to be a beauty, with huge, expressive eyes, and exquisitely proportioned to boot, was certainly no virtuoso. When she attempted showy feats like the thirty-two fouettés of the evil Black Swan, she zigzagged precariously towards the orchestra pit as the turns grew increasingly feeble. Her contemporary, the Bolshoi Ballet’s incomparable Galina Ulanova, who with a few steps could convince you that the human spirit was a visible substance, had the face and build of a farmhand.

Generally speaking, the less tangible attributes turn out to be the most significant ones. A ballerina can act, where acting is called for. Far more interesting, however, is her ability to express or suggest feeling even in abstract ballets, lending them a subtext of implications that keeps them from looking like infernal machines. She has, too, an enormous vein of fantasy and the capacity, through it, to ignite the audience’s imagination. Without stooping to the vulgarity of egoism — ideally, a ballerina is modest — she exercises a strong personal charisma. She fascinates you; literally, you can’t take your eyes off her. A nascent ballerina will stand out in the most obscure reaches of the ensemble. And yet the ballerina is by no means a solo show; as the critic Edwin Denby once observed, she can “spread a radiance over the rest of the cast and the entire stage.” She has mettle — an abundance of physical and psychic energy and the daring to risk it continually. The supreme hazard — allowing herself to be wholly open and vulnerable emotionally — is one she eagerly tackles on a daily basis, before an audience of strangers. Above all, she’s distinguished by a spiritual dimension that seems to be inborn. A ballerina may provide her public with visceral thrills of various sorts, but her special department is transcendence.

School of American Ballet students with the New York City Ballet. Photograph by Paul Kolnik. May not be reproduced without permission.

While companies with the clout of ABT and NYCB can, today, pick and choose from a huge number of physically gorgeous and technically spectacular dancers, they don’t find (or nurture) many who possess the intangible ballerina qualities. Why? Because, I suspect, the type is rapidly vanishing from society at large. The Romantic mode of selfless aspiration, of dedication to an ideal, of single-minded commitment has simply gone out of style. Currently we live in a savagely pragmatic world, and this discourages the more ingenuous virtues. If we’re guided by a vision, we know it’s not cool to admit it. Imagine the hoots that, today, would greet a remark like Fonteyn’s “I dance every performance as if it were going to be my last.”

This attitude-shift in our culture is, to my mind, the primary reason for the disappearance of the ballerina, but secondary factors abound. Today’s near-maniacal emphasis on technique also inhibits her development. The dance audience has become fixated on athletic prowess; you’d think it was watching the Olympics. Ironically, this avidity for multiple pirouettes in uncanny forms and aerial feats that seriously challenge the laws of gravity is self-defeating. There’s a point – and we’re edging close to it – beyond which the human body can’t go; once most of a company’s ensemble as well as its stars have reached that level of prowess, extravagant bravura loses its zest for the spectator. I’ve had the disconcerting experience of observing a company class that finished with nearly every woman in the studio whipping off those damned thirty-two fouettés, in unison. More is often less.

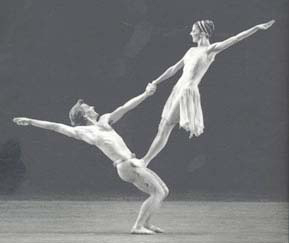

Sandra Brown and Johan Renvall

Needless to say, superficial feminist thought condemns the ballerina role for a woman. The traditional ballerina is perceived as fragile, passive, dependent on her male partner’s support — in other words, politically incorrect. As long as we misapply sociological values to art and scorn all cultural values but local ones, the sylphide model is not going to stage a comeback. Actually, those sylphides and swans are strong as longshoremen (longshorepersons?) and their partnered work is a paradigm of cooperation between the sexes, an extended miracle of cantilevering, balance, and timing. What’s more, modern choreography for the ballerina makes her look empowered to a degree never dreamed of by the princesses and poetic wraiths depicted in nineteenth century classics. This evolution has been accompanied by a change in the nature of pointe work. In the nineteenth century its purpose was to make the woman appear delicate; today, both the dancer’s technique and her toe shoes are far sturdier, and the effect can be Amazonian.

Present-day conditions — some beyond human control, others capable of remedy if only there were more time, money, and purity of purpose — limit the cultivation of ballerinas. Dance is a tough art; so much depends on circumstances. While a writer can work alone and in obscurity (think of Emily Dickinson), a complex and hard-to-come-by support system is required to develop a ballerina. She needs first-class choreography to teach her how to dance; classroom work alone will never do the job. And not only should she have a rich repertory available to her, she should, ideally, also have ballets created on her by a master who will instinctively tailor the dance to her anatomy, her skills, her temperament. He (classical-ballet choreographers are most often male; it’s a Pygmalion-and-Galatea thing) will enhance her gifts, conceal her weak points, and, most important in promoting the performer’s growth, unveil facets of her heretofore unrecognized. “He would reveal you to yourself,” the French-bred NYCB star Violette Verdy liked to observe about Balanchine — without whom Suzanne Farrell, Patricia McBride, and many another idiosyncratic talent might not even have had a significant career. Unfortunately, choreographers of worth are rare, and we are living through a particularly dry time, while the golden-oldie ballets are difficult to preserve in the style proper to them and still more difficult to retrieve if they’ve been shut away in storage for too long.

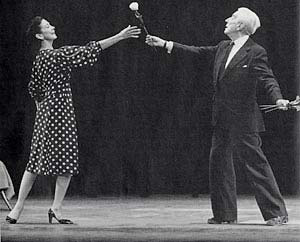

Fonteyn and Ashton. Photograph by Leslie E. Spatt. May not be reproduced without permission.

A potential ballerina also requires an artistic director who is perceptive about her needs and in a position to respond to them, someone who knows what can and should be done with the raw material she offers. Fonteyn was the most fortunate of beings; her choreographer was Frederick Ashton, who shaped the aesthetic of England’s Royal Ballet; her artistic director was the founder of that company, Ninette de Valois, who commented, on her first glimpse of the fifteen-year-old then called Peggy Hookham, “We are just in time to save her feet,” and only a few years later thrust her into leading roles in the classics. A ballerina also requires one-on-one coaching — either from her choreographer or, in time-hallowed roles, from an astute and generous predecessor with a gift for instruction. This is a lot to ask. Like choreographers, artistic directors of genius are not abundant, and their creative freedom has been increasingly restricted by boards of directors fixated on the bottom line. In the coaching department, ABT does what it can, which isn’t enough; NYCB has given short shrift to the possibility of coaching from the ballerinas Balanchine molded, Farrell foremost. All in all, the outlook is discouraging.

It’s not that the scene lacks raw material. The female ensembles of both companies, it’s commonly proposed, offer enough burgeoning talent to provide every company in this country with a ballerina. The NYCB has eagerly promoted the flowering of Maria Kowroski, a breathtaking adagio dancer who reminds veteran viewers of the young Farrell. Yet, despite her phenomenal gifts, Kowroski is usually at a loss in allegro work and, worse, at a loss when it comes to knowing who she is and what she’s doing on stage. Too often her performances are vague and unfocused because she’s hasn’t yet learned how to inhabit her roles. Who will help her? Granted, she’s only twenty-four, but she’s already been with the company for six years, trusted with significant assignments from the very start. If she’s worth cultivating, the process should be inextricably linked to every challenge given to her.

ABT’s rising generation — a cornucopia of talent — is headed at the moment by the stunning Gillian Murphy, all regal authority and confident technique. So far, though — I write just after her debut as Odette/Odile in “Swan Lake” — she has failed to reveal the vein of fantasy and individual expression essential to a ballerina. Her demeanor is invariably grave, that handsome face frozen into a mask of retro glamour, the lush, big-boned body disciplined to a tautness that is understandable in an aspirant bent on perfection and success. Now that tight rein needs to be relaxed so that she can enter the human dimension in which the self is acknowledged, vulnerability is admitted, and artistry happens. Perhaps Murphy can manage this metamorphosis on her own; she appears to have a more self-sufficient temperament than Kowroski. The tragedy of a self-made dancer, though, is that she can be seen to be working in a vacuum.

Nina Ananiashvili

A ballerina is not an isolated phenomenon; she is the construct and the emblem of an artistic community. Perhaps it’s for this reason that Nina Ananiashvili, one of the most lustrous dancers of our day, has been shortchanged in her ongoing relationship with ABT. The company seems to perceive her as belonging to a “foreign school” of dancing, and showcases her exquisitely in that way, but has not been able to integrate her as one of its own. While Ananiashvili’s dual emphasis on plastique and impassioned theatrics does indeed recall her great Soviet-school predecessors, she is unusually “teachable,” eager to absorb fresh takes on the classical tradition. The freest and most soulful performance I’ve seen her give was in Balanchine’s “Mozartiana,” staged and coached for Bolshoi dancers by Farrell.

Further depleting the ballerina ranks among our American-trained dancers is the dismaying increase in abortive careers witnessed in the last fifteen years or so. A corps member identified early on as ballerina material is likely to be plucked out of the ensemble too soon and overburdened with responsibility instead of being allowed — and helped — to mature gradually. Today’s wunderkind is too often tomorrow’s burnt-out case. The NYCB’s lovely Miranda Weese, who seemed every inch a ballerina-in-the-making, has gone into a baffling eclipse, just as, a decade earlier, ABT’s Amanda McKerrow, a crystalline dancer with the touching air of a princess in exile began to fade from the scene without ever realizing her full potential. Yes, injuries, illness, and failures of confidence play their part in such sad trajectories, but one wonders if the salvage rate couldn’t be bettered.

The hardiest survivors of forced development, in which vicious competition plays its inevitable part, sometimes turn tough and calculating, able to foster their prominence but not serve their art. Others — I think of ABT’s Paloma Herrera — are corrupted by circumstances into becoming caricatures of their most saleable qualities. No one seems to mourn what has been lost; the prevailing mood is eagerness for the next potential star. Today’s audience has a ravenous appetite for novelty — this is a disease that pervades our entire culture — and so the turnover is swift. Like so many commodities, the newest discoveries efface previous ones before the older ones have really had their day. Besides being wasteful and cruel, this frenetic turnover works dead against the best interests of an art bound by its very nature to tradition.

The only way, perhaps, to live with these difficult truths is to admit that an era is irrevocably over. The world of classical dancing is reconstructing itself according to radically different conditions and values. Ballet is very likely to continue and flourish without ballerinas as we once knew them, and, in its new guise, will no doubt find a responsive audience — probably a young and inexperienced one. The seasoned viewer who is unable or unwilling to journey into this cooler and harsher domain may have to rest content with memories.

© 2007 Tobi Tobias