I wasn’t sure whether or not problemization was a word until I looked it up and found that it is one. Problemization is to consider or treat as a problem (Merriam Webster).

I’ve been thinking about this a lot. The reason is that increasingly when you look at a foundation’s grant guidelines you are asked: “What problem are you trying to solve?” I put the following into Google: “Foundation funding what problem are you trying to solve.â€Â The search result: 182 million hits that included dozens of foundations’ guidelines and many articles about how to write successful grant proposals. The additional question is “What is the need or problem that will be eliminated if your request is granted?†(And subsequent questions about how you identified and documented the problem, what logic model you followed to design your solution and how will you measure your results.)

I wonder what effect this culture of pathology, of diagnosis and treatment, is having on the nonprofit sector in general and the cultural sector in particular. Do foundations increasingly see themselves in the role of a sort of benevolent physician, identifying social “disease†and using their grants as the medication needed for wellness to be achieved? Not that long ago, a primary framework for organized philanthropy was one of ideas and experimentation; the mindset was one of risk capital and the ability to fuel new ideas that are interesting and should be tried.

The problem/solution framework is especially insidious for the arts. Yes, we do solve problems in the arts, particularly we work on aesthetic and philosophical problems, though these are not problems a foundation could help solve (at least not directly). In fact, the problems we solve are not easily documented, it is difficult to apply a social scientist’s approach to them, and our documentation of results is more likely qualitative than quantitative.

What problems are we trying to solve? Here are a few. More people should encounter beauty as part of their daily lives. Artists who are able to focus uninterrupted time on their creative work will create stronger work, work that will create more meaning and value for those who encounter it. All people deserve access to the transformative power of artmaking, and its ability to simultaneously draw on the physical, intellectual and spiritual aspects of being human. The creative impulse is as basic to our species as the need for food and cultivating individual creativity will result in richer, fuller lives.  Communities should have permanent structures where creativity can be fostered and artists can find meaningful work. There are many more.  But, do we really see these as problems?

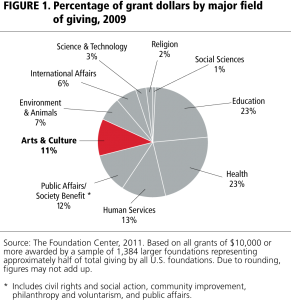

I think that people working in the arts see the world through the lens of human potential and not through the lens of disease (or human failing). I wonder whether this accounts for the widening chasm between foundation priorities and arts giving (arts grantmaking is shrinking as a proportion of overall grantmaking, down 21% between 2008 and 2009). Perhaps the reason is that those in the cultural sector are unwilling (and unable) to re-orient their deep-seated belief in human potential to satisfy an analysis by those who look at society and see what’s wrong, rather than what’s right.

Problemization is a world view and the nonprofit sector seems only too willing to embrace it. You may argue that this has meant more rigor, more focus on results, and better outcomes. But something also has been lost. Maybe you can help me put my finger on it.