[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Now my fourth — and next to last — post on changing the conservatory curriculum. I’ve linked the others at the end.

Remember that I’m offering free consulting sessions! Originally I’d thought they’d be about changing the curriculum, but in fact the gratifying response has also come from people who wanted help with other things. Especially career development. Which I’m happy to help with, just as I’m happy to talk about anything in your work that might need an outside eye, and some advice. Of course one reason I’m doing this is to get paid clients. But if in a free session I can give you concrete help, I’ll gladly do it. Contact me, and we’ll set up a time.

So this post is about how we teach — and how we should teach — classical music history. Which, under the old ideas of classical music supremacy, was called simply music history. But let’s not belabor that point right now. And this may surprise some readers, but I’m not going to insist here that conservatory students should learn the history of other kinds of music.

I think they should, but save that for another time. Because if students are going to study classical music, then of course they should know its history. And there are issues right there — with no thought of any other musical history — that need to be aired.

History of what?

So what is the history of classical music? Traditionally it’s taught as the history of composition. Bach used these forms and harmonies, Mozart these, and then what he (and his contemporaries) did evolved into what Beethoven did. And onward. Starting deep in the past, with Gregorian chant. And focused — always and just about exclusively — on the great composers.

But this is only one part of the history of music. The great composers, for one thing, weren’t the only ones writing. Mozart wasn’t, not by miles, the leading composer in Vienna in his day. Shouldn’t we learn who was, what that person’s music was like, and, rather crucially, why he was popular and Mozart wasn’t?

We can’t simplistically assume that the popular composer was a shallow crowd-pleaser, and that Mozart was too good to be popular. Handel and Haydn (toward the end of his life), Rossini, Verdi, and even Brahms (in some of his works) were very popular. Wagner swept the world, after the controversy over his music faded away. We need to learn how popularity works, how popular composers can easily be good, and, above all, what musical life in past centuries really was like.

Which means we also need to know about the audience. Who were they? How did they listen?

And What did they make of the music they heard? To take only the simplest aspect of this, we often hear about masterworks — the Rite of Spring! Carmen — that failed at first hearing. But what does this mean? Other masterworks, like Haydn’s London symphonies, were immediate triumphs.

And we’re much less likely to talk about works, even by the great composers, that were popular once, but now aren’t much played. Like Beethoven’s early Quintet for Piano and Winds. Why, in their day, did these pieces succeed more reaily than the ones we now revere?

I could make a long list of things we don’t talk about, in music history courses. And one crucial point would be finances. How did musicians in centuries past make a living?

What we miss

By not talking (or not talking very much) about the subjevts I’ve mentioned, we miss a lot. In fact, we miss the entire texture — the real-life existence, as part of the larger world — of music in the past. Which then means we don’t really know how even the great composers lived and worked.

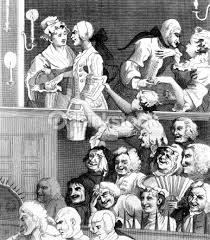

In the 18th century (and often in the 19th) audiences talked during the music. And applauded, while the music still was playing, when they heard something they liked.

Richard Taruskin (in his amazing five-volume solo performance, The Oxford History of Western Music), compares the scene in a box at a Baroque opera performance to a family in our time, watching a TV show at home together. Making comments freely and having other conversations while the show proceeds. (Though in the Baroque era there could also be shouted conversations between the audience and the singers on stage.)

Richard Taruskin (in his amazing five-volume solo performance, The Oxford History of Western Music), compares the scene in a box at a Baroque opera performance to a family in our time, watching a TV show at home together. Making comments freely and having other conversations while the show proceeds. (Though in the Baroque era there could also be shouted conversations between the audience and the singers on stage.)

Does knowing all this, about the audience, change our understanding of the music? I’d think it does. When I watched the DVD of the Met Opera’s production of Rossin’s Armida, I came — through not liking all the music very much — to a new understanding of Rossini. He wrote his operas knowing full well that if people didn’t like an aria or duet, they simply wouldn’t listen. Which then made it his job to get their attention, in whatever way he could. (In L’Italiana in Algerí, there’s secco recitative. Long ago I noticed that when the recitatives end, the aria, duet, or ensemble that follows is almost always announced with two loud chords from the orchestra. Why? Probably to let people know that now came something they might want to hear.)

Likewise Baroque opera. It’s hard to pretend that Handel or Vivaldi wrote masterworks only — as sometimes we like to pretend — with only drama uppermost in mind. Their first job (especially Handel’s, since he owned two of the opera companies that performed his works in London), was to make sure the people in their audience had a good time, so they’d come back and buy tickets again.

And so Handel improvised at the keyboard, with such élan that his playing became an attraction in itself. Vivaldi played — as high and fast as possible — flights of crazy fancy on his violin.

The players in the orchestra also improvised. And to understand what the singers did, first we have to rid ourselves of any thought that the da capo aria — the standard form in 18th century opera, which permeates almost every piece you’re likely to hear — is rigid. Or that its purpose was in any way to suit some conception of serious drama.

Yes, there’s always an opening seciton, then something that contrasts, and then a repeat of the opening. Seems very formal, but not to the 18th century singers or audience! The singers improvised, changing the music at will, especially during the opening section’s repeat, where they’d unleash such a torrent of crazy fast singing that the composer’s melody might disappear.

Audiences lived for that. And also for spectacular sets and scenic effects. And for gossip! They gossiped about what the female singers wore, and certainly about the scandalous sex lives of the castratos (castrated men who sang leading roles, and whose castration left them infertile, but not impotent; some were gay, some were straight, and the straight ones quite wonderfully couldn’t get an aristocratic female lover pregnant).

And such scandal about Vivaldi! Who in his later life traveled through Italy, producing his operas, openly living with two much younger women who’d been his pupils at the girls’ school in Venice where he so famously taught. Don’t think that people in the 18th century didn’t draw the same conclusions from this living arrangement that we might. Plus — adding such spice to the scandal — Vivaldi was a priest! Who (more scandal) hadn’t said mass in decades.

Coming to a temporary close

I’ll stop here for now, and say more in my next post. But one last thought. Maybe some people think that, well, fine, all the things I’ve talked about really did happen, but the great composers disapproved, and put up with it reluctantly.

There’s no evidence for that. Mozart wrote a famous letter, telling his father how he’d composed his Paris symphony, structuring the piece to make the audience applaud. (In the middle of the music.) He doesn’t sound reluctant. If anything, he sounds gleeful, and happily proud of how well his plans worked.

Vivaldi, as I’ve said, made sure to entertain his audience. Would he have gone to such lengths if he disapproved?

When Handel made his London debut as a composer with his opera Rinaldo, he had dragons flying through the air breathing fire. And to give extra appeal to a garden scene, he released birds into the theater. Something he hardly needed to do, since his music, featuring sopranino recorder as the song of the birds, is delicious all by itself.

But release birds he did, though it didn’t work out very well. The birds wouldn’t leave, and did what birds will do, right on the heads of the audience.

If all these things went on — and I’ve only given a few snapshots; there’s much, much more — then don’t our music history courses give little idea of what music in the past really was like?

So then we don’t know where our masterworks really came from. And we don’t know what classical music really is. Which makes it harder for us to make changes in what we do now.

My previous posts on curriculum change:

“Changing the curriculum” (why we have to do it)

“The highest road” (about entrepreneurship, and why the tension some people feel between teaching entrepreneurship and teaching music doesn’t need to be there)

“Music theory for a new century” (about why a literate musician today needs to analyze many kinds of music)

Greg, thank you for your postings on music theory and history. There are so many ideas that have run through my head over the years on these topics and their place in a college/conservatory music curriculum that it’s difficult to limit my thoughts, much like the teaching of these topics themselves. I’ll stick with four points (standard lecture format, hey?).

The position of classical music in higher education reminds me of the position of Judaism and Christianity in American life. It used to be that those two religions were the players of significance in the U.S. (outside the largest metro areas and California). The only challenges to their dominance were made by atheists, agnostics, and freethinkers. Today, just about every community has a host of different religions and organized non-religions present. It used to be that Classical music was the only player of significance in higher education. To the world outside colleges and conservatories, traditional Classical music is a minority “religion.” How different the situation is at most music schools (I don’t think I’ve ever seen busts of Jimi Hendrix or Taylor Swift adorning the walls of such schools, let alone Ravi Shankar or Earl Scruggs.) To challenge musical orthodoxy by admitting the existence and substantial presence of other types of music, most of which grow in non-academic soil, is often considered apostasy or heresy. Serious contemplation of such musics at the higher education level is often treated with contempt, disdain, or condescension—“pandering to the masses or to special interest groups.” Of course, today most large music programs have some jazz and world music programs. The existence of such programs in itself provides a healthy challenge for the core curriculum. I think that smaller programs that can’t afford to branch out too much tend to cling to the orthodox curriculum. It is perhaps to those programs that some music publishers pay attention to when producing textbooks.

The roadblocks to successful teaching of music theory and history tend to be predictable. Many students want to master, perform, and teach music they already have some experience with and, hopefully, passion for. For some, this boils down to developing technique and learning repertoire. Anything that takes them away from the practice room or the stage is a speed bump. Many teachers of performance focus on certain techniques and repertoire. (I doubt if many voice teachers will embrace autotune any time soon.) They teach what they care about and feel that they know. Some of these teachers incorporate aspects of music theory (including analysis) and history in their teaching, but some do not. Students who are not naturally interested in music theory and/or history will likely not get much help integrating their study of theory and history with performance teachers who largely ignore these subjects and might even treat them with some disparagement. Even highly gifted teachers of theory and history I know often wonder what use their students will make of the processes and ideas explored in their classes.

This second idea leads directly into the third. In the Classical music world there tend to be a division between absolutist and contextualist views of music. I hold to a contextualist view, but many of my former colleagues (I’m now retired from teaching, but not from the “practice” of music) were (are) staunch absolutists. While they might admit the advantage of theory and analysis as tools for learning and understanding, history is another thing. In my dual role as a teacher of music history/literature and piano performance, I always presented composers and pieces of music as part of an environment. I developed a thread where context affects aesthetics which affects how composers use different techniques. In the time of Haydn and Mozart, for example, public concerts were a new thing and were a part of a rising middle class. In some respects, the growth of the Classical style reflects attention to this new group of listeners. Composers wanted to engage listeners, who might indeed be talking or gossiping during a performance. Those who engaged listeners the most, or even didn’t care much if they carried on during a concert, were usually the most popular. Mozart was very well aware of this fact. He might not have been happy being number 7 in popularity among opera goers in Vienna, but I don’t think he could bring himself to do what it would take to be number 1. When playing a minuet, it helps to have danced a minuet. Does musical phrasing have anything to do with dance patterns and dance steps? How does the fact that Berlioz never (to my knowledge) played the piano affect his orchestration practices (versus say, Brahms)?

My final point (I promise!) is notion that women and “minority” composers continue to be woefully unrepresented on traditional classical concerts. This circumstance leads to the assumption that they have written nothing worthy of inclusion, and might be programmed from time to time as a novelty. They will never be “staples” on the Classical concert stage. It will also be some time before any white male composer of today is “canonized” as well. This reality of concert life might lead female and minority students to believe that there’s not really a place at the table for them as composers. I always enjoyed talking with students about the status of women at the Paris Conservatory in the 19th and early 20th centuries and how Lili and Nadia Boulanger helped change it to some degree. It’s also interesting to have a discussion about the social and musical situation of Mrs. H.H.A. Beach (not Amy Beach, please) in the U.S. in the early 20th century.

Please excuse any botched metaphors or comparisons and any long-windedness on my part. I only hope that the learning environments in both theory and history will open up to a larger world without sacrificing the discipline, rigor, and passion needed for musicians to be successful. (With a healthy injection of joy and enthusiasm, please!) Musicians still have to be able to deliver the goods. Personally, I always felt that as a teacher of music history/literature and piano performance, the questions I asked students were always far more important than the answers I gave them. They’ll come to their own conclusions anyway – I hope. Both the “scubaists” and the “snorkelists” out there have to admit that sound is the musician’s water and water is at its base H2O wherever you go. Salaam Shalom Namaste Peace be with you Hi