[contextly_auto_sidebar]

This summer came a CD release which — with all respect to the major classical music forces involved — is the kind of project I wish we wouldn’t do.

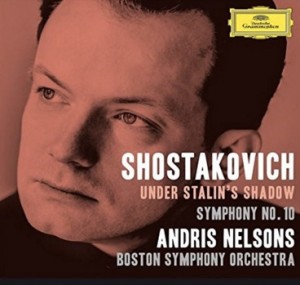

This was a Deutsche Grammophon recording, Andris Nelsons conducting his Boston Symphony in two Shostakovich works, the Tenth Symphony and the Passacaglia from Lady Macbeth of Misensk, packaged unitl the title Shostakovich Under Stalin’s Shadow.

This was a Deutsche Grammophon recording, Andris Nelsons conducting his Boston Symphony in two Shostakovich works, the Tenth Symphony and the Passacaglia from Lady Macbeth of Misensk, packaged unitl the title Shostakovich Under Stalin’s Shadow.

And it all seems so thoughtful, so serious. And so connected to the larger world.

The new recording initiative will focus on works composed during the period of Shostakovich’s difficult relationship with Stalin and the Soviet regime— starting with his fall from favor in the mid-1930s and the composition and highly acclaimed premiere of his Fifth Symphony, and through the premiere of the composer’s Tenth Symphony, one of the composer’s finest, most characteristic orchestral works, purportedly written as a response to Stalin’s death in 1953.

That’s from DG’s press release, which I received by email. But the problem — and, really now, how obvious is this, once you think about it? — is that not many people care.

And I say that even though I care (though see below), because I’m a Communist history buff, and Stalin fascinates me. I’m eager to read the first 900-page book in Stephen Kotkin’s new three-volume biography.

But out in the wider world, do many other people care? Of course they don’t. Stalin — and much less Shostakovich’s life under his rule — aren’t active topics of discussion. They’re history, not part of our present life.

So why do we in classical music keep trotting them out, in performances, discussions, recordings, even in theater presentations built around musical performances?

I think it’s because we’re looking for relevance. We want to reach outside our bubble, and connect to larger things. And to more people.

But Stalin won’t do it. In fact, I think the mere mention of him only shows how stuck we are in the past. Underlines this. Shouts it to the world.

And so we ought to stop. No more Shostakovich and Stalin.

And, while we’re at it, let’s retire some of our other unconvincing steps toward relevance:

- No more about Brahms and the Schumanns (which quite a part from no one outside classical music caring, is at best a minor-league love story).

- No more Dvořák in America.

- No more Shakespeare and music. (Even though Shakespeare is wonderful, and relevant for theater companies to perform. Or they can make it so. But when, for the thousdandth time, we bring forth our long-dead composers and show how Shakespeare inspired them, we’ree going backwards.

All we do, by stressing these tired stories — over and over — is…well, I said it. We just show the world how fixated we are on the past.

[ADDED LATER] I’m not saying we won’t attract a few more people with these programs. There’s always someone who’ll be interested, or who’ll be drawn by the thought of something new, or something unusual in classical music, especially if we do these themes with theater, or some other nontraditional format. But we’ll never break out of our bubble with these things. We’ll never have any wide appeal.

So enough! Let’s connect ourselves to things that people care about today.

And on the subject of Shostakovich and the Communist regime (since Soviet history is something I know a bit about) I’ll explain in my next post how we miss the real story in our Shostakovich/Stalin presentations. How complex it all is, and how fascinating. And how many opportunities we miss — if we’re going to go there — to really bring the history alive.

Greg, although I tend to agree with most of your musings, I think you missed the mark here. Symphonies can be a focal point for multi-disciplinary examinations of music’s place in a larger, historical context. And just because it’s history, it doesn’t mean it’s not interesting, and perhaps on a good day, even compelling. The relationship of Shostakovich and Stalin can be more than a mere faded historical footnote. The Pacific Symphony recently participated with Chapman University in producing an extensive, well attended festival centered on the life and context of Shostakovich. (https://www.pacificsymphony.org/shostakovich_festival). But you won’t pick on us unless we produce a CD, right?

Hi, Mike. Good to hear from you. I’d reply to you as I’ve replied to others — I’m not saying the Shotakovich history isn’t interesting or relevant. Only that it won’t draw many people in. By citing the educational project the Pacific Symphony did (which may have been wonderful), I think you underline my point. It takes something that major to develop interest. And so bravo for doing it, but, once more, simply crying out the names of Shostakovich and Stalin won’t by itself get people interested. Further, educational projects, on any level (elementary school to something like what you did) aren’t the answer to the survival and thriving of orchestras in our age. What we need is box office — things that people instantly respond to. And, once more, though Shostakovich and Stalin may be a story a thousand times worth telling, in themselves those names don’t provide the instant box office we need.

An experiment I would like to see: For the period of one year, any time a music director or curator wants to program Shostakovich, substitute a composition by Galina Ustvolskaya or Alfred Schnittke.instead.

This doesn’t strike me as a very well-considered post. If only the issues posed by Stalin and Shostakovich were part of a dead past. If only mass terror and art’s attempt to respond to it were irrelevant for our world. Try telling the artists in China and Putin’s Russia that there’s nothing to be gotten out of the story of Shostakovich and his relation to an oppressive regime. Try telling it to artists in Britain and America looking at Guantanamo and state-sanctioned torture. The notion that history is “not part of our present life” seems wrong-headed. Try Faulkner: “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” Contemporary classical music may speak to our present more directly, but the idea that narratives of love, death, terror, and courage have nothing to say to us because they are old and “tired” is false. People respond to those narratives when they know them. The back of a CD can’t present that narrative in a very compelling way but when I lecture on Shostakovich and the 5th Symphony to a roomful of college students–and then play them that music–they feel its power. What’s “tired” to you, an expert committed to new music, is no measure of what people with no such exposure will find compelling. And if they like DSCH, then there’s a path ahead to Schoenberg and Henze and Pärt, all of whom have roles in the larger narrative in which Shostakovich and Stalin play a part.

Robert, same thing to you that I said to Andy. Don’t confuse general issues with specific cases. The issues you mention are alive today, but the memory of Shostakovich and Stalin isn’t nearly so vivid. In effect you’re saying that people _should_ be concerned with Shostakovich and Stalin, and maybe they would be if they learned about what went on. But they won’t be drawn in to learn no matter how strongly we headline the names. You mentioned Guantanamo. Good connection. If DG released a CD probing the Guantanamo problem, don’t you think there’d be more response. Or, as I said to Andy, if we did a concert about the restrictions on teaching evolution some states impose, then we’d also get response. But just because you feel the Shostakovich issues are still relevant today doesn’t mean people will respond to the name.

Greg,

I am very curious as to where you are going with this in the next installment.

“Connect(ing) ourselves to things that people care about today” would certainly include what it was like for Shostakovich to live under complete and thorough socialism, in a place where thoughts could be crimes and everyone was in fear of being labeled politically incorrect, aka anti-revolutionary. It’s shocking for me to see a younger generation that neither experienced one of the darkest chapters in the 20th century through real time news or even their history studies. Music of various eras is certainly a window to stimulate such investigations.

Hi, Andy. Don’t confuse the general issue you raise — a very big one — with the specifics involved in Shostakovich’s case. People may care about the general issue, but not respond to the names Shostakovich and Stalin. If we could find a way to connect to, let’s say, states that restrict the teaching of evolution and control the way it’s written about in textbooks, then we might get instant interest.

I don’t quite agree with you, Greg, although I do think the people at DGG missed a chance here to make their recording more relevant than they did.

In January of this year I broadcast my own 2-hr program that included the Shostakovich 5th Symphony where I highlighted Shostakovich’s work in light of his continual battle with government censorship (including threats on his life). It was not long after the heinous attack on Charlie Hebdo offices, so I dedicated my program to the theme of music and artistic censorship and freedom of expression, My playlist included works by Hindemith, Pfitzner, Beethoven, Harris, and Shostakovich.

While few people may resonate or care about Shostakovich’s plight during Stalin’s reign of terror, his struggle is still relevant to today in light of all the censorship (in arts, textbooks, anti-science, etc.) that are continually in the headlines.

I think *linking* current issues to their historic analogs/counterparts reminds us these things have always been with us. In Shostakovich’s case, he not only suffered under the regime, he sought to subvert their efforts with and within his art. What could be more heroic and relevant?

Heroic and relevant for sure (though see my upcoming post for a moment that was less than heroic; complex figure, S was). But only heroic and relevant once people hear about it. As a way to draw them in, it’s not likely to work, because they won’t, right out of the box, be interested enough to find out why they’d be interested. That’s our dilemma. In any case, as I’m going to post, there’s much we normally miss about this story.

Although the Shostakovich-Stalin story is interesting and relevant, so is Prokofiev’s relationship to Stalin, and Aaron Copland’s to FDR, and Mozart’s to two or three nobles, etc., etc. You know what I have never seen, in over fifty years of concert attendance? A program note on the relationship of Prokofiev’s music to Shostakovich’s! Wouldn’t that be more enlightening? Shostakovich’s connections to jazz are important, too, it being the anti-establishment music of his era; how about comparing this to more recent composers’ relationships to rock and roll? That might even interest some people younger than sixty.

Actually, 60 is pretty much exactly the age of people who grew up when rock was popular and anti-establishment.

Now, if you want to talk about composers’ relationship to EDM…

(Of course, Mason Bates for one already has that covered – and it’s made him America’s “second-most performed living composer”! Too bad his music isn’t better.)

Robert, my assistant goes through the blog and approves comments. But not always immediately. Don’t be concerned. Yours will get through. If we didn’t have the approval process, we’d have too much spam, as I’ve learned from experience.

A belated “Oh God, yes, thank you for saying it!” to every single prescription in the above piece.