[contextly_auto_sidebar id=”JtNvwUOYK69GvdLi2R9Ikdv7nqFKTN1T”]

So much fuss about Peter Gelb, so many accusations flying!

And not just from the unions he’s locked in battle with. I’m late to this discussion, but what got my attention was Norman Lebrecht saying that Peter was not only wrong, but was lying — outright lying — when he says that attendance at opera performances (and at classical music events generally) is falling, both in the US and in Europe

Lebrecht:

This is untrue, and Peter knows it is untrue.

The Lyric has just reported record results. So have Vienna, Amsterdam, Dresden and more. We’ve reported these results on slippedisc.com over the past couple of weeks.

Peter Gelb is out there telling the world that opera is doomed when others are getting off their butts and making it bigger and better.

If everyone else thinks opera is growing and Peter Gelb alone insists it is doomed, what we have here is not an artistic crisis but a clinical dysfunction at the top of the Met.

But is this how we ought to think about these things?

Is opera attendance rising or falling in the US?

Is opera attendance rising or falling in the US?

Yes, some companies are doing well. That would be true even if the entire field was doing badly. It’s a basic principle of statistics. And of common sense. If you look at a large enough sample of opera companies — or shoe manufacturers, or dairy farmers, or any group you care to name — a few will be doing much better than the norm, and a few will be doing much worse.

So you can always find success stories. But in the larger picture, they’re meaningless. What you want to know is what the norm is — what’s happening to most shoe manufacturers. Or opera companies. Maybe the Chicago Lyric is having wonderful years, but how’s the field doing as a whole?

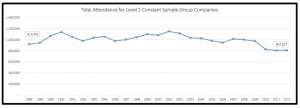

As it happens, we have an answer for that. Back in September, I asked my invaluable assistant, Caroline Firman, to contact classical music service organizations in the US, and ask if they had information on ticket sales in the area of classical music they deal with. Kate Place, research director of Opera America, supplied a chart showing attendance from 1988 to 2012 at all the larger US opera companies, taken together:

So Peter Gelb may be right. These numbers aren’t complete. We don’t know how smaller companies are doing. Kate Place says that not enough of them report their data for her to feel that she can say how they’re doing as a group. But what’s happening at the larger companies is clear. Ever since 2001, they’ve been selling fewer tickets. Maybe the numbers picked up since 2012, but what would that mean? A two-year increase wouldn’t reverse the trend. (Unless, of course, it brought the numbers right back up to where they were in 2001, but as we’ll see in just a moment, even at the Chicago Lyric that’s not close to happening.)

The importance of context

Let’s look more closely at the Lyric’s reported success. Yes, the company announced what sound like good results for their 2014 fiscal year. (See also here.) Ticket sales up by 8%, fundraising up.

But how did they do the year before? Really badly. In their 2012-13 season, ticket sales were only 83% of capacity, down from 88% the season before. That’s a 9.4% drop.

So now they’re doing better. If, when they talk about their 2014 fiscal year they mean the 2013-14 season, which just ended, their 8% sales increase brings them back up to 89.6% of capacity.But all that does is wipe out the drop from the year before. It doesn’t establish any kind of long-term trend.

And are you ready for this? Even at 89.6% of capacity they’re down — way down — from a stunning 103% in the 1990s.

How did they sell 103% of their tickets? It’s simple. When subscribers couldn’t go to performances, they’d give the tickets back without asking for a refund. And the company would then resell those seats to single-ticket buyers.

I remember those days well. I wanted to know how they’d sold 103% (which meant selling out even the contemporary operas they produced), and so I called them and had an informative talk with a member of their marketing staff. They were marketing demons, I learned. If seats were unsold for a 20th century or contemporary opera, they’d get on the phone to anyone in their database who’d ever bought a ticket to such a work, and talk them into buying yet another one.

But that was then. Now we have a ticket sales decline from 103% of capacity down to 89.6%. That’s a fall — from the 1990s to 2014 — of 13%. Or 20%, if you use the 2012-2013 numbers. (Which for all anyone knows could return in 2014-15.)

This isn’t a success story. It’s a story about a long-term decline. The Lyric might now announce what seem, in the present climate, like wonderful results, but in the past 20 years they’ve taken a big hit to their bottom line. Which hardly refutes what Peter Gelb said. Instead, it provides supporting evidence suggesting that he’s right.

More coming. We still need to look at the health of opera in Europe. And at why Peter Gelb sits in the center of so much commotion.

Two points to remember:

When you want to know how an entire field is doing, don’t cherrypick your facts. Get comprehensive data.

And when you do discuss an individual case, put it in the proper context.

Has anyone pointed out the irony yet of Norman Lebrecht accusing others of lying to make classical music seem more doomed than it really is?

I believe that Klaus Heymann of Naxos recently made that observation about Lebrecht. In a courtroom, in fact. With some success.

Bless your heart for using real numbers, Greg, but these are opera people and they don’t do numbers.

Actually, they do do numbers, but they cherry pick the ones that fit their beliefs, they make illogical connections between unrelated statistics, and they conflate qualitative observations with quantitative measures. They’ll even do it after an institution has actually died to rationalize their belief in opera’s immortality.

Normally I believe it’s wise to ask arts administrators to focus on facts, but when it comes to opera, I think we’re dealing with a culture that’s incapable of understanding itself in relation to the world on which its survival depends.

Might as well ask Marie Antoinette to understand bread shortages.

Trevor, I think you speak from experience! We could have an interesting talk, you and I, about classical music and numbers. The field as a whole doesn’t have good data on itself, and seems unconcerned about that. And then what happens when the numbers are in fact known? They’re not publicized, or in the case of orchestras, even kept secret. Which then means that the institutions lose an incentive — public shame — to fix their problems. An orchestra that admitted it had been losing ticket sales since 1990 would naturally be asked what it planned to do about that. An orchestra that’s losing sales but not admitting it can temporize quite a bit, even internally.

I’m really surprised more people haven’t commented on the fact that Chicago only made those ticket sales numbers by programming 30 (!) performances–a third of their season–of The Sound of Music, amplified, with only two opera singers in the cast. So I’m not sure how you could say the numbers support an argument that opera is thriving in Chicago (though it sounds like musicals are doing fine.)

Good point, John. I didn’t want to appear to bash them, and also didn’t want to make the post too long. But yes, they’re now doing one musical each year. Interesting, though, that the first one they did, in 2012-13, Oklahoma, only sold 65% of its tickets. I don’t know how Sound of Music did. But even if the musicals don’t sell so well, they lead to a couple of sad reflections.

I want to make clear that I like musicals (quite a lot, in fact), and have nothing against opera companies programming them. But it’s sobering to think that in the 1990s the Chicago Lyric could do contemporary or 20th century opera and have full houses, whereas now they’re doing Oklahoma to 65%. When they announced that figure, they said it was what they expected to sell, so that leads to another sad thought: That they may have felt in such potential trouble about ticket sales that they scheduled a musical, expecting not to sell many tickets — but that, just possibly, it’s better than they expected to do if they’d scheduled another opera.

It’s also true that their programming seems much more anodyne than it used to be. A focus on popular pieces. That can be a bad strategy, even if it sells more tickets initially, because a feeling develops that the company doesn’t do much that’s interesting.

Lyric Opera of Chicago has enjoyed great success over multiple decades. Yes, 103% sales is eye-catching but it was true during the 90’s.

I don’t get the bashing of producing musicals however. Here we are talking about what classical music organizations need to do better in their offerings and in selling tickets.

Lyric seems to have found a way to do this. Sound of Music sold extremely well. Ticket sales were robust and did indeed comprise a large percentage of total season sales. But so what?

It is a great piece of musical theater. Classical one could even say. And it was well marketed and it connected with those audiences who went and heard it. My friends in the orchestra enjoyed performing it.

So why is this a bad thing? And perhaps it should be duplicated at companies such as San Diego that may be on the edge of faltering.