I’m continuing my posts about the classical music crisis, and I’m coming now to the crisis timeline, which will how and when the crisis developed, decade by decade. I started these posts by asking when the crisis began. Here are some answers, in three parts. First, two snapshots. Then, tomorrow, a savvy overview, written as a comment to my original post. And on Thursday a detailed timeline.

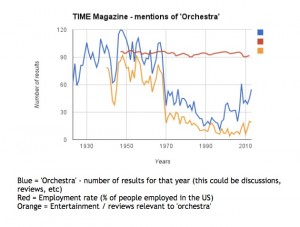

Two snapshots. First: a graph showing mentions of the word “orchestra,” tracked year by year through every issue of Time magazine from its founding in 1923 to the present. This was emailed to me by Michael Di Mauro, who searched the Time website for mentions of orchestras, and graphed the result:

You can download this, if you’d like to see it more clearly. Could the meaning of it be any clearer? It shows classical music losing its force in American culture. The mentions of orchestras — in both articles and music reviews — fell by two-thirds in 1969, and continued to fall after that, picking up only in the past few years. But not by much, and for the most part only in articles, not reviews. It’s easy to guess that the mentions were due to the current orchestra crisis — that orchestras, to Time, were newsworthy because they were failing, not because of the music they played.

Time, I should note — though currently just a ghost of its former self — was for decades one of America’s top magazines, right up through the end of the last century. What it covered is one way to measure what Americans thought was important.

Which leads me to snapshot two: classical music on the cover of Time, as tallied two years ago by Yvonne Frindle, Publications Editor and Music Presentation Manager.for the Sydney Symphony, who’s a reader of this blog. She presented this data on her own blog, in the form of a graphic, beautifully done, but too big to read easily here. You can download it.

What it shows (just like Michael Di Mauro’s graph) is what Yvonne calls “classical music’s changing prominence in culture.” Or rather its declining prominence. As Yvonne said in her blog, around three quarters of Time‘s classical music covers — from the start of the magazine in 1923 to 2011 — appeared before 1956. And there hasn’t been one since 1986. (That last classical music cover, 27 years ago, showed Vladimir Horowitz.)

Many thanks to Michael and Yvonne for all the work they did to bring us this data. We’re all in their debt.

The crisis series so far:

How long has the crisis been going on?

Why that question — how long the crisis has been with us — is hard for most of us to answer

Before the crisis — what classical music in the US was like before the crisis hit

Some thoughts on crisis skeptics

Portrait of the crisis — hitting all parts of the classical music business

basically what I am witnessing in my lifetime is the END of Western Culture as we knew it. I am 53 years old, and I remember clearly how my friends and I would wait at the Sam Goody in Massapequa, NY, for the latest classical albums to be released. I remember attending concerts at Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall, and those concerts were sold out. Now? It is not an issue to purchase a ticket as there are more empty seats than there are ones that are sold. Bye bye orchestras and classical music. Hello sports, Lady GaGa, and Miley Cyrus! How disgusting!

Perhaps the pop music was more fun than the garbage of the mid-20th Century?

What a good point you’ve made, Mr. Sandow: .”The larger picture shows classical music as a healthy, vibrant, central part of our society at least through the 1960s.And then…”

There were several huge changes during the ’70s about the kind of “entertainment” we had available and how we participated in it: (1) availability of cable TV/satellite TV all over the country. (2) invention of the VCR for home use; (3) invention of the Sony Walkman; (4) invention of the personal computer (the IBM PC Junior, 1978.) All of these changed FOREVER they way we listen to music, watched TV and movies, and how we could have unlimited entertainment on demand. We are still feeling these repercussions today.

Another part of the problem — the elephant in the room so to speak — was that the establishment of the NEA in 1965 spawned thousands of new arts organizations all over the map so, by the end of the ’70s/early ’80s, there was a glut of arts groups in the country who could never be supported and still can not be today.

BTW…there’s a big difference between talking about a ” crisis in classical music” and a “crisis of how professional symphony orchestras can survive in the 21st century. It’s great that people are downloading more classical music than ever before or that a string quartet does a gig in a bar. But operating a 52 week per year orchestra, with 90+ musicians on the payroll, is quite another thing.

I see a radical decrease in attendance in many organizations: organized religion, classical music, jazz, etc. I was at a concert by Christian Howes (one of the best jazz violinists out there)–about 80 people showed up. I think our biggest challenge is that there is just so much out there—and for so much of it you don’t even have to leave your house.

Christopher Brooks is absolutely right. Today’s “target audience” — ie., twenty somethings, thirty somethings, etc. has only known a world where unlimited entertainment is available 24/7 right in their own homes.

Still, many millions of people will shell out $100 dollars 6 months in advance to attend a rock concert. Granted it may be once or twice a year they do that… but examine what they are anticipating: a spectacle or new sights and sounds, to hear (meet) a favorite celebrity/personalty/rebel, to sing a long with that person without disturbing anyone, to dance to their music, to be “blown away” by a wall of sound, to hang out with like-minded friends, to drink and be rowdy, to SEE something that’s NOT on the commercial releases, to take a video home to share with friends, and to brag that they were there at all. And if that’s not a communal experience, I don’t know what is.

Can classical music do anything like this? I’d say YouTube Symphony already has, and there will be more in the near future. The Philly Orchestra pop up last week is proof that the occasional “carnival atmosphere” of an impromptu event might just be what orchestras need to balance (shake out) the perceived stuffiness of the tradition. Spontaneous experimentation with engagement methods, like the conducting competition (after the Conduct Us video), serve to bring the audience onstage by proxy. It would get old to do this every week… but once in a while surprises a new audience. I want my audiences to say to their friends, “It’s about time they started doing this with classical!” We can even advertise events that are “New Classical” and which are traditional (pure). We could even have a sliding scale.

Some very good points from Rick Robinson however statistics show that attendance for rock concerts is also down, along with jazz, Latin music, many sporting events, etc.

Larry, that’s audience fragmentation. There are far more entertainment options today than there ever were, so smaller pieces of pie for any one live entertainment option.

U2 has consistently been the highest grossing touring act for years and yet didn’t turn a profit during their 2009 360° tour and Lady Gaga went bankrupt during her Monster Ball tour in 2011. The “Who is Paul McCartney” twitter stampede after his Grammy Performance literally made me laugh out loud.

Sports audience decline is starting to become a give too. Interesting to see that the NBA is having a difficult time filling stadiums even by giving away tickets; the NFL wants to institute wifi for their declining audiences so they can “transform live games into multimedia entertainment extravaganzas.” And Sports teams often lie about attendance because since those numbers can affect blackout rules and sponsorships–in other words, it can affect non-performance revenue which is the lion’s share of all sports revenue.

The irony is how often solutions being suggested for changing classical music culture are those which both the Sports and Pop Music industry have done, but which aren’t working much for them any longer. So again, the Classical Music field is behind the times being two steps behind the popular entertainment industries.

The sixties do indeed mark a turning point in the importance of classical music in American culture. This is tied to the phenomenon loosely known as the sixties generation, (my generation) which was that group of young adults who defined themselves by a package of interrelated traits.

Members of the sixties generation;

1. were vehemently against the Vietnam war

2. Passionately in favor of racial equality

3. Used drugs

4. Sexually liberated

5. Identified with rock music and regarded it as the music of their generation.

This was the package which was generally adopted by the best and the brightest of that entire generation. More specifically it was adopted by those people who, in former times would have gravitated to classical music. The sixties generation adopted rock music as it’s own, and the lyrics of social protest that went with it. Rock music became young people’s music and the expression of the now legitimized social protest, and has remained so to this day. However the former protesters, now aging and respectable, have by in large not joined the classical music audience as their parents and grandparents did.

So, perhaps this accounts, at least in part for the phenomenon of the Time Magazine covers.

The comment about “huge changes during the 70s” reminds me of a music class that my younger daughter (who plays flute, clarinet, alto sax and electric bass) took when she was in college around 1981. The instructor reminded the students that “Until about a hundred years ago, if you heard music, someone was playing it.” This was just after the 100th anniversary of Thomas Edison’s “talking machine”.

@Larry: well pointed out. Are you professionally involved in classical music? You sound like the kind of person who should be at classical next.

Yes, I am a professional involved with classical music, for the past 44 years.

I notice that you are equating the term orchestra with ‘classical music’. I would suggest that your comments might address the declining influence of the ‘orchestra’, not the declining viability of classical music.

Your post last week about the programs that begain in Whitehorse, Yukon Territory were very much about the vibrancy of classical music.

It’s a simplistic univariate analysis as well. Individual articles in the Time Magazine shrank in number after the death of foundery, Henry Luce, in 1967. There was less of everything in favor of the longer “Time Essay” pieces which we now associate with this newsweekly magazine. A more useful historicometric measurement would be the proportion of word count for Orchestras (or classical music) against the total word count.

Jon, two things might be said of your hypothesis.

First, it seems unlikely on its face. The number of items in Time mentioning orchestras decreased to less than a third of what they’d been in the past. Can this have been due largely to a change in format? Hardly seems possible. There were, after Luce’s death, so many fewer items in each issue of the magazine?

The other thing to say is that your hypothesis can easily be tested. All we have to do is search for some word that — thinking of the overall state of our culture — would be as likely to show up in, let’s say, the 1930s and the 1970s. So i searched for “baseball.” The word appeared in 82 articles in 1939, and 71 in 1979. If your hypothesis proved true, we’d expect to see many fewer articles with baseball in them in 1979. But we don’t. The hypothesis appears to fail.

That’s why a simple univariate analysis of data doesn’t tell us much and why I would suggest a bivariate (at the least) analysis of word count versus number of articles. A trivariate analysis compariing the proportion articles in each issue would be best and would actually tell us something.

And if you’re looking at the broader historical context. With the passing of the Sports broadcasting act of 1964, Television became the primary medium and revenue source for sports, functioning in a similar “non-performance” income source for sports that donors and foundations serve in the non-prof world. After the passing of that act, which legally allowed sports teams to function as cartels to collectively package and sell broadcast rights of games, there was naturally more media coverage.

Once media conglomerates started to rise after the 60s it was in the best interests of newspapers and magazines to promote their economic interests and products (in a similar way that happened with Pop music). With the two factors of favorable legislation (some have criticized it as preferential legislation, since cartels function to shut out competitors–hence why we a number of leagues in favor of the 3, and then 4 that we now have in the US) and favorable rising media giants (ironically, also allowed to happen by legislation since all corporate mergers must be approved by an allowed to happen by federal legislation) it should be no surprise that Sports wouldn’t see as much of a decline in all media (though that’s now changing as traditional broadcast media is declining).

The sad fact is that the classical music world never could figure out a way to capitalize on the newer media (television) as it did with the broadcast medium it replaced (radio) as the new dominant media.

In other words, a univariate analysis of one magazine amongst all the print, broadcast, and [now] digital media coverage doesn’t tell us much without the broader historical context that gives us a bigger picture than a cherry picked example.

Am I saying that Classical Music isn’t having problems? No. But it’s not necessarily the problem(s) we think they are. It’s as I commented to Liza on your facebook wall when she mentioned that “The media is a reflection of what interests the public. If they want people to buy their magazines etc., they have to cover stories that interest the public.”

Media corporations can drive things far more than audiences. And in the case of sports, as revenue through Broadcast rights increasingly become the lion’s share of total revenue over the dwindling proportion of ticket/gate revenue (interesting that this parallels what happens in the arts with decreasing proportion of ticket revenue over increasing proportion non-performance revenue), it makes perfect sense to see an increase in media coverage. It’s just too bad the Classical Music field couldn’t (or wouldn’t) create this kind of symbiotic partnership in the way that Sports (and Pop Music) has done.

Oh, and by word count–that’s referring to word count of the articles. 10 articles about orchestras averaging 50 words apiece is smaller than one piece about orchestras totaling 1000 numbers.

I’m looking at the second page of the first issue of the times–there are seven different pieces on it. The lowest word count per piece is 36 (not including title) and the largest is 322. There are only a handful of small photos (usually of people) scattered throughout the issue–each takes up roughly the same space as the average sized article (roughly 150 words).

Telling us the word Orchestra itself is mentioned less (or has declined more) doesn’t tell us much if a piece about orchestras in post 1969 articles take up more page space (ie wordcount). And your baseball example doesn’t tell us piece about baseball actually contain the word “baseball” in them with more or less frequency than pieces about orchestras.

Far too many ways to look at the whole issue and that’s why wee have statisticians who’ve developed different kinds of statistical analyses that get beyond simplistic univariate descriptions like the above so we can understand things in context.

Jerry, I think you have something here. The 1930’s began the boom of big bands or dance bands which were often referred to as orchestras. Here are a few, Duke Ellington Orchestra, Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra, Benny Goodman Orchestra, Tommy Dorsey, Count Basie,and on and on. Also Desi Arnez, Guy Lombardo, and the like. And then there was Mantovani and Kostelanetz.Orchestras were never more popular than the 1930’s through the 1950’s. The majority, however, didn’t happen to be symphony orchestras.

The “dumbing down” of culture to the lowest common denominator – the crude violence on tv and in movies…..all appeal to the basest of emotions. The music we are all talking about appeals to the highest and most elevated of ideals and emotions. When the general population is surrounded by the “easy titillation”, they aren’t inspired to seek out more ennobling experiences. How can we fight that? How can we make the press cover Carnegie Hall rather than Kardashians?

I think many ARE ready for more ennobling music… but in alternation with music for fun. As long as they can access the music, many curious, young people are looking to round out their knowledge base and music collections with something completely different. What’s old becomes new again when presented as an alternative or in a new context.

Conversely, instrumental music (as are most symphonies) also appeal to base emotions. One just needs to be shown the LANGUAGE of music. One marvelous way to do this is with DANCE, which often reflects the rhythms, direction, drama and contrast of instrumental music. There are Isadore Duncan societies which may already have these aesthetics in mind. Else, many choreographers would be happy to have the work. Best of all, “interpretive content” is not an either-or suggestion… rather may be incorporated selectively or even quite separately from the action onstage to build an audience for it.

I have many more suggestions but let’s start there.

I get slightly different results using Google’s ngram app on “Beethoven.” We hit peak Beethoven 1945-1950, and then there is a SHARP plunge (sorry not to add the image) that continues into the 1980s, and then a rambly plateau to today. Interesting to note that “Beethoven” started falling out of the cultural conversation well before Woodstock. I first did the query expecting to see a spike around 1970, the Beethoven bicentennial, and I was quite surprised by the results. No spike in 1970, but a huge spike around WW II. Dit-dit-dit-dah?

Dave, I think the 1940s spike might be due to the music appreciation movement, which was so widespread in the 1940s. Maybe a lot of introductory books about classical music was published. Or, as you suggest, it could have been due to the use of the the rhythm at the start of Beethoven’s Fifth as a symbol of V for Victory. From Morse Code, wasn’t it?

Anyhow, thanks so much for doing this! We should make many more searches — opera, chamber music, for instance. And see what we find.

Congratulations–I really enjoy reading this–very insightful and relevant.

This decline is disconcerting and demoralising but we should not quit or despair–

let us think of new strategies. In fact, I am setting up an orchestra (in Melbourne, Australia) with a friend which will perform both Western classical and Chinese folk music–we are market-oriented as there is a large Chinese community here–we also intend to introduce Asian music alongside Chinese in 2015 onwards. The bulk of our repertoire will still be Western classical—

we are trying to bring West and East together –our name is Australian-Asian Orchestra which will debut on 16th Feb 2014 in Melbourne. A major aim is to perform in regional Victoria so that we can serve local needs.

Dr. Lim–this is wonderful! I actually often blog about non-Western Orchestras in the US and around the world (here’s my most recent post about Chinese Ensembles in New York City) and often perform with musicians from all around the world in various non-Western styles. I would love to hear more about your orchestra and good luck with your debut concert!

re “dumbing down of the culture”: I’m reading Berlioz’s Evenings with the Orchestra. Interesting how few of the composers he mentions are still played, and (according to Berlioz) what dreck they played to please an utterly boorish audience. But they were working–and getting paid, albeit poorly.