I’m grateful to everyone who answered me — here, on Facebook, and on Twitter — when in a blog post I asked how long the classical music crisis has been going on. And I’m also grateful for the lively discussion that followed.

When I asked the question (in the post I’ve linked to above), I said I thought we’d learn something from the inquiry. And that’s certainly been true. Several people offered some detailed memories of when they saw the crisis hitting, often in the course of work they were doing in the classical music world. These people — in a future post I’ll pass on what they said — are helping to outline what up to now has been a hidden history.

But what I think the responses most show — and it’s a powerful lesson — is that we don’t know how to talk about our crisis. Some people think it’s been going on for ages, maybe perpetually, and some people don’t think it’s even real. I’ll have responses to those thoughts, again in future posts, because I’m going to do a series of posts on the crisis, on what it is, why it’s real, and how long (when we look at all the available information) it really has been going on.

But what I think the responses most show — and it’s a powerful lesson — is that we don’t know how to talk about our crisis. Some people think it’s been going on for ages, maybe perpetually, and some people don’t think it’s even real. I’ll have responses to those thoughts, again in future posts, because I’m going to do a series of posts on the crisis, on what it is, why it’s real, and how long (when we look at all the available information) it really has been going on.

But for now I want to say that we in classical music don’t know how to talk about our crisis because the information we’d need to know what’s going on isn’t readily available. There are many reasons for this, but one of them is what I can only call a reluctance — or something like that — to gather information. You’d think, with all the talk of a crisis, that people in classical music would be hungry for data, would be demanding it, would be saying (for instance) let’s gather and publish data on how many tickets are being sold to classical music events, now and in past years going back a couple of decades, so we can see if there’s a decline, and if so, how large it is.

But we don’t do that. More on this in future posts, but to me it’s almost shocking how little we know, and how little we seem to care that we know so little. It shows, I think, a striking immaturity in our industry, and an unwillingness to face what’s really going on.

To show how little we know, let me make a comparison, one I fear I’ve made before, but will continue to make until I’m blue in the face. Or until my typing fingers turn blue.If we were talking not about classical music, but instead about American newspapers — another industry in crisis — we’d know exactly where we stood.

Everyone knows what the newspaper crisis is about. Fewer people are reading print newspapers, and fewer advertisers are advertising in them. Both these things mean a loss in revenue. Many readers have migrated to reading newspapers online, and newspapers have tried to make money from that, by charging for access and by selling online ads, but this revenue doesn’t equal the money the industry used to make from print. So newspapers seem unsustainable, and have responded to these problems with extensive cutbacks, which if anything make the problem worse, because now the papers aren’t as good as they used to be, giving people less reason to read them.

Details of these problems are readily available. Look, for instance, at the story that ran in the New York Times back in August when the Times sold the Boston Globe, which it had owned since 1993:

According to the Alliance for Audited Media, circulation at The Globe from Monday through Friday declined 38 percent in 2013 from 2003, to 245,572 from 402,423. Before the Times Company bought The Globe in 1993, it had a weekday circulation of 506,996.

As circulation declined, so did advertising. According to the second-quarter earnings statement released by the Times Company on Thursday, advertising revenue for the New England Media Group dropped 9.5 percent, to $44.4 million, compared with the same quarter in 2012.

If we had information like that about leading classical music institutions — big orchestras, for instance, or opera companies — we’d be talking very differently, and with much more confidence, about where our field is heading.

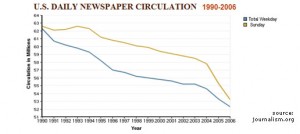

Long-term information about newspapers is easy to find. One thing I found, in two or three minutes online, was this graphic, showing the decline in newspaper readership since 1990:

And I found a Washington Post article from 2009, in which I read this:

U.S. newspaper circulation has hit its lowest level in seven decades, as papers across the country lost 10.6 percent of their paying readers from April through September, compared with a year earlier.

The newest numbers on newspaper circulation, released Monday by the Audit Bureau of Circulations, paint a dismal picture for an industry already feeling the pressures of an advertising slump coupled with the worst business downturn since the Great Depression.

The ABC data estimate that 30.4 million Americans now pay to buy a newspaper Monday through Saturday, on average, and about 40 million do so on Sunday. These figures come from 379 of the nation’s largest newspapers. In 1940, 41.1 million Americans bought a daily newspaper, according to the Newspaper Association of America.

Average daily circulation of all U.S. newspapers has been in decline since 1987 as papers have faced mounting competition for reader attention and advertising. Online, newspapers are still a success — but only in readership, not in profit. Ads on newspaper Internet sites sell for pennies on the dollar compared with ads in their ink-on-paper cousins.

The newspaper crisis is thoroughly quantified, and well understood. And transparent, since all the crucial data is easily available to anyone who wants it. Our crisis is none of those things.

I know you were just using newspaper circulation numbers as an example, but have you ever thought about the fact that the classical crisis is closely connected with circulation decreases? How do you think those audiences heard about the classical concerts they attended en masse just a few decades ago? Think about the people who still attend those concerts now and how much they overlap with the people who still subscribe to print newspapers.

It seems to me as though the ignorance about the details of the “classical music crisis” may be due, not so much to fear of what might be discovered, but to a combination of complacency and devotion by musicians to the music.

Not being a professional musician, only an amateur and an audience member, I can’t be sure of how the professionals have been operating, but I imagine they generally have been going on a feeling that audiences have always showed up to concerts (whatever their numbers) and been appreciative of what they hear (or the recordings they buy), and anyway the business details need to be left to the management people who have heads for business — just let us go ahead making the music as we always have.

Now the crisis is more apparent to everyone (or a lot of people, anyway), but the data weren’t being accumulated all along as systematically as they were in the newspaper business, which was always understood to be a business.

“One thing I found, in two or three minutes online, was this graphic, showing the decline in newspaper readership since 1990”

I hate infographics which imply that a 16% decline is something like a 90% decline. It should be more like this: http://static.guim.co.uk/sys-images/Media/Pix/pictures/2010/3/10/1268220314766/google-newspaper-circulat-001.jpg

Your point is well-taken, though the chart you linked to looks pretty devastating, especially since it puts the current decline in a longer context.

But sometimes an objective graphic doesn’t tell the whole story. If you think the graph I used is too sensational, from a statistical point of view, I don’t think anyone could deny that the effect of the circulation decline on the newspaper business has been has been sensational. So the graphic that might be exaggerated, if you’re thinking purely of numbers, isn’t out of line as an impressionistic picture of what’s happened to the newspaper business.

It just suggests that no one will be reading newspapers by… well, 2014. It certainly is a bit sensational 🙂

I’ve been down this road many times, Greg, and I’m convinced that the reason we don’t seek the market intelligence we need is that it will reflect a reality we refuse to face. Arts professionals – especially in classical music – don’t want a clear, objective, fact-based description of reality because it will force them to change in ways they find intolerable. Or worse, they don’t want to learn that they no longer occupy an elevated position in western culture’s value hierarchy. Most arts leaders believe they’re on top when, in reality, survival demands they compete on a value-neutral playing field alongside everyone else for a share of an increasingly fragmented market. On some level these leaders know that seeking honest market data will force them to accept their more humble, democratic, we-need-you-more-than-you-need-us positions, and many will go well out of their way to avoid doing that.

Excellent point!

I think one of the reasons why the crisis in classical music is hard to talk about — and why some will deny it exists — is because in many ways it’s a crisis of “soft” support, rather than the “hard” kind. And soft support problems can’t be readily gleaned from hard statistics about ticket sales, etc.

For instance, when Van Cliburn won the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958, he got a ticker-tape parade in New York and the cover of Time magazine. What winner of a classical music competition would get a fraction of that kind of media attention today? Similarly when Itzhak Perlman was first introduced to American audiences, 1958, it was through the Ed Sullivan show — the most widely watched talent show of the day.

The attention that these two artists received in back in 1958 were significant both for their cause and effect. People in high places in the mass media felt that enough people were interested in these artists to justify this kind of exposure. And the middle-class population, exposed to these artists in this way, felt assured that they were prominent figures — and that it behooved them to at least know a little about them.

Today, while there is evidence to suggest that the “core” audience for classical music and opera remains strong (at least within America’s more successful musical institutions), the outlying would-be soft supporters — people who, in former times, might be casually interested this art form — are looking elsewhere. Certainly the mass media is not telling them otherwise.

I don’t think this is a very comforting picture. Classical music in America has always been very much dependent on soft support — the support of people who feel that it’s “important” to have a local symphony orchestra, even though they would rarely (if ever) attend a performance.

When did the crisis begin? It is said that a mountain starts to shrink as soon as it stops growing. So, by applying the same line of thinking, I’d say that the crisis began in 1958, when classical music in America seemed to be on top of the world.

Colin, the soft crisis you describe is very real, and quite dramatic. But there’s no way that it doesn’t translate into a hard crisis with tangible, in some ways devastating effects. The classical music audience, just for instance, has been getting older ever since (approximately) the late 1960s. Which means that it’s shrinking. Audiences are smaller than they used to be. We might not notice that from the outside, because if ticket sales drop from 94% of the house to 87% (I’m making these numbers up), you don’t really notice the difference. By looking at the audience, I mean. But if you’re the organization selling the tickets, then for sure you notice. The impact on your bottom line is intense, and very likely you start running a deficit.

Classical music is in the business of pretending that it is not a business. As Christopher Small points out in his book “Musicking,” classical music events are set up to obscure any connection with money. There won’t be talk (as there is in pro sports, for example) about what individual players are paid, or about how much the business made last year. Newspapers, on the other hand, are clearly businesses, and they’re not embarrassed about it. Contrast classical music with other kinds of music, where an artist’s success may be measured in albums sold and annual profits. In classical music we seem to believe that the business side of our work is unseemly, so we don’t collect many numbers, and we don’t share what numbers we have. And we don’t like talk about our business being in trouble, not just because we don’t want to admit there’s a crisis, but because we don’t see ourselves as a business.

John, nice to hear from you.

A little anecdote. One night, at a dinner party in a city that’s not New York, the development director of one of the Big Five orchestras amused us all by telling us how cutthroat her department was. They followed every large real estate deal in their city, to discover people with a lot of money whom they hadn’t talked to yet. And they looked at every will that was probated, for the same reason.

You can’t tell me that she wasn’t thinking her orchestra was a business, or that her boss, the Executive Director, didn’t know how her department operated. These organizations may not like to talk as if they were a business, but from the inside, they certainly know they are.

I’ve been in meetings with a group of orchestra executive directors and also with a group of marketing directors. Same story. They talked like businesspeople. Baffled businesspeople, maybe, but businesspeople.

A lot of what you say is true, though. I’d add that I think these people are to some extent paralyzed, because they know they have to change, but don’t want to make changes as large as those that will be needed. So it’s easier for them to be fuzzy in public about problems they’re much sharper about when they speak privately. If they were honest in public, their donors would expect them to offer solutions to their problems. And since they can’t yet do that, they’d be in trouble.

Agreed. A key difference – newspapers are mostly publicly traded and have duties to shareholders. Their trends are public because that information is not proprietary. Orchestras are usually closely held non-profits with boards (mostly rich or privileged people) who are accountable to no-one. Look at Minnesota – not even the musicians have been allowed to review the orchestra’s books. There is simply no way even to compile the information you are seeking unless the orchestras themselves agree to — or their funders’ demand — an unprecedented level of transparency. Perhaps that is the answer — the foundations who contribute (and who are granted access to at least some revenue information) could be the catalysts for a proper collective review of the state of the music community.

From another point of view, you’d think nonprofit institutions that depend on public support — both from donors and from government — would have even more reason to be honest about their condition. Or at least as much obligation to be so. If donors are easier to fool than investors, well, that does make sense. But some donors have seen through the facade. Look at all the talk about “donor fatigue” among people who’ve given money to orchestras.

However, the necessity of the fundraiser and executive director (and even the board) to remain continually upbeat about their product in order to entice and attract donors is one of the reasons that this “Pollyanna-ish” delusion exists. Our product is not newspapers — it will never bring in the revenue needed, which is why we must fund-raise. The continued slide of the balance of earned vs. unearned income is where the “crisis” lies.

Hi Greg,

You and your readers may be interested to know my book: The Symphony Orchestra in Crisis: A Conductor’s View, is available on Amazon, discussing the very questions you ask. Perhaps you could propose a larger debate about this current crisis, which orchestras and communities are doing well and why, and what we can all do beyond simply talking about it. Thanks for sharing! All best, John

http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Symphony-Orchestra-Crisis-ebook/dp/B00EZBK8VQ/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1378372621&sr=8-1&keywords=symphony+orchestra+in+crisis

Have we referenced this? (I know it is only one sector…)

2011: http://abo.wearepapertree.com/media/20110/ABO-KEY-FACTS_2011.pdf

I presume that as they conduct regular surveys this may become useful.

And the PROMS data would be helpful. Maybe they should publish it as I presume they can calculate tickets sold etc… and radio and internet viewings per year?

Then YouTube and iTunes probably have similar data per region or country on the amount of classical music sold.

And non-genre specific but interesting nonetheless:

2011: http://www.prsformusic.com/aboutus/corporateresources/reportsandpublications/addinguptheindustry2011/Documents/Economic%20Insight%2011%20Dec.pdf

2010: http://prsformusic.com/creators/news/research/Documents/AddingUpTheUKMusicIndustry2010.pdf

2009: http://prsformusic.com/creators/news/research/Documents/Economic%20Insight%2020%20web.pdf

Major markets such as LA, San Fran, NY and Chicago have large audiences for classical music and probably always will. Their major orchestras may have problems with the cost structure of their organizations but that will be fixed, in time, albeit with painful labor disruptions. The problem as I see it is that cities that are not defined by their culture are the ones where classical music is fading. And this creates serious problems in the classical music business because a domestic career in the US cannot be defined by a few cities. Not to mention the ability of an orchestra or chamber ensemble to go on a proper tour.

Poor Mr. Eatock like most “classical music ” observers is oblivious to facts – The van Cliburn

comparison to the present day is much uninformed or a romantic reading at its worst . Mr.

Cliburn was given a ticker tape as an answer to the Khrushchev bear hug Mr. Cliburn

received after winning the competition.Mr. Cliburn was embraced by the Russians when they

noticed how shabbily he was ignored by his countrymen( embassy) while other contestants had the backing of theirs -(food , lodging rehearsal halls etc ). We were not to be outdone by a shoe thumping Russian who observed “we know how to treat artists “. The ticker tape parade was

a “political ” answer to Khrushchev and had nothing to do with past “better ” times . To-day such

a parade would not come about, as it would serve no purpose . Ed Sullivan introduced every body , opera stars pop singers even a talking mouse. Nowadays we have weekly shows where

everyone aims to be a star. It is not a crisis but an evolution .

What you describe is not just a crisis of support, but more broadly a crisis of identity. Having served for a number of years on the administrative staff of a major orchestra, I have witnessed this issue first-hand.

Internal to the administration, I witnessed the struggle between the “artistic” side of the organization, whose focus is on the artistic value of the work presented, and the marketing/sales side, which focuses on the promotion and sales of the works and the seats, as well as promoting the brand of the org in general. I have also watched the struggle between the administration and the musicians, who to often act like independent, distrustful partners rather than the conjoined twins they actually are.

The delicate balance these dynamic (and sometimes opposing) forces must achieve to both produce an artistically legitimate AND financially viable product is still not easily done. Nor is convincing the musicians that they must (for their own sake) participate in that balance. Many times, I watched them act in ways that were directly contrary to the best interest of the organization, or refuse to participate in the promotion of the org. From my perspective, the issue seemed to be a refusal to fully acknowledge the necessity of maintaining not just an artistically pure organization, but a financially sustainable one as well. While marketers (which I am not) would not presume to tell these professional musicians how to play their music, the musicians often derided the reasonable and necessary steps the (equally professional) marketers took to promote the concerts. The artistic components of the org (artistic and the musicians) still seem to chafe at the idea that marketing (or ticket services, or other parts of the admin staff) should even be necessary. “Isn’t this about the music?” This naivete must be overcome and a realistic symbiosis achieved.

As stated above, the “soft” edges of popular support are now more distracted than ever, and no amount of musical purity will bring them back. Broad-based, diverse efforts to reach out to the less-than-fervent fan base (including marketing, PR, outreach, fundraising, etc) in this day and age to sustain a large arts org, pure and simple. Ideally, a blend between artistic purity and more accessible and financially sustainable works are (perhaps unfortunately) necessary…or the orchestras must resign themselves to accepting their shrinking future – playing smaller venues for smaller audiences, and having less of reach into education and relevance in the broader community that is so important to the long-term viability of the Arts. For all our sakes, I hope they find this balance soon and can maintain it.

I’m not sure I can accept there is a ‘crisis’ in classical music. There are too many success stories, full houses, great series & thriving ensembles to describe a bone fide crisis.

I’m a little reluctant to comment here, as I feel I’m coming to your postings mid-thought, however, I perceive there to be two issues that frequently get conflated, and should not.

There is a global economic crisis. Quite astonishingly, many musicians seem to feel this should not impact them. However, for reasons too obvious to here enumerate, arts funding is the first victim of a financial constriction and the last to recover. I direct a 24 season-old chamber music group. From it’s peak in 2008, it saw approximately a 30% decline in its budget and now it’s coming back. That financial profile mirrors that of the value my home. Coincidence? Not at all. My group has been heavily impacted by the recession, but throughout ticket sales have continued to grow.

My group has been horribly impacted by a financial crisis, and however badly it swept the rug out from under our collective artistic feet across the world — which it certainly did — it is a financial crisis, not a crisis in classical music.

I suggest what is most often described as a crisis is, in fact, a paradigm shift. Mr. Sandow’s illustration of the newspaper industry can serve us here too. With the decline of the newspaper industry, is information less available to us? Not at all, indeed there is more information more readily available to us than ever before. Are large pieces of paper, covered in symbols generated in big factories the primary medium for transmission of that information? No. There’s been a paradigm shift in the distribution of information. A very successful paradigm shift, that is beneficial to everyone except those associated with newspapers. This dilemma, however, is correctly identified as a newspaper crisis not an information crisis.

In our field, I suggest we are witnessing a paradigm shift, not a crisis. Some wish to cling to the models that were already challenged in the late 20th century. If you wish to do that, the ensemble I can best offer to you for comparison is the band that played on the deck of the Titanic! For that band, that was a crisis. For bands around the rest of the world … not so much!

We are in the midst of a paradigm shift which, by its nature, means the shift will involve the dissolution of some traditions and ensembles we may have become very fond of. For those institutions … this is a crisis. However, at this time, there is more great music, superbly composed, magnificently performed, available to more people than ever before. Creativity appears to be boundaryless, and cultures from around the globe — many predating the European cultures — have employed this musical form for expression. That speaks to the durability of this form.

I can easily agree that having more information available to us would be much better to measure this assessment, so I’m all for that — for it’s time to paint the true, positive picture — classical music is at the most creative, fertile & dynamic time in its history. America, indeed, may be leading the 2nd renaissance for our art. That does not a crisis describe!

Thank you.

Have you really read Sandow’s historical comparisons? In earlier blogs for Musicweb-International I noted that Olin Downes’ classical music programs on early TV registered up to 8 million viewers for a much smaller TV population. Arturo Toscanini’s NBC symphony broadcasts regularly reached 4 million viewers. The biggest classical listenership today is probably WETA Washington’s all classical programs with ~500,000 listeners. In the 1950s virtually all children got exposure to and knowledge of classical music, and nearly all radio programs featured classical music intros. Except for children with special family or other background most young people today are rock based.

I regret hammering on negatives, but must point out former chief classical music critic for the Washington Post, Tim Page’s observation in a full-page Millenium special that since 1950 no new orchestral compositions have been accepted by audiences.

I say these things you not to disparage the music you love, but to point out that the mass of general music-loving audiences is not a legitimate focus of attention for contemporary composers. No conservatory student can get a degree in composition composing music that nonprofessional audiences really like. There is no music for children comparable to that of the past, and a separate group of composers, unrecognized by the music establishment, composes music for contemporary worship.

So I invite you to lend your estimable musical skills and background to efforts to broaden the music establishment’s focus.

Cordially, Frank T. Manheim

Dear Mr. Manheim,

Thank you for your gracious compliment on my musical skills, which I’ll accept with gratitude. To the remainder of your sentence I shall say, indeed I am attempting to broaden the musical establishment’s focus … that has been a mission of my organization for over two decades.

This evening (Sept. 26th) my group will present the last of 5 performances of the following program:

Harbison, Four Songs of Solitude

Serry, Night Rhapsody

Huang Ruo, To the Four Corners

Harbison, Songs America Loves to Sing

Novacek, Four Rags for Two Jons

This program — a wide-ranging program by U.S. or U.S.-based composers, all very much alive, has enjoyed great audience reception in almost full houses — standing ovations at intermission and at the end the of the concert.

I hasten to add, the group I direct is not a new music group; next month we migrate to Auerbach (ok she’s still alive too) and Mozart, and the following month all-Beethoven.

What we have done, over years, is develop an audience interested in the *live* musical experience. An intellectually curious audience willing to engage and explore with our musicians. The ability to listen to new music (whether it’s the-ink-is-still-wet-new or just hasn’t-been-before-heard-new is immaterial) informs and refreshes the reception of the accepted masterworks.

In the printed concert program’s introduction I include the following sentence:

“Across the country we see groups, mostly orchestras, mired in trouble — a primary cause being a harvest of ever-diminishing interest from decades of stultified programming paired with a passive performance experience. An aging audience is not the problem — that’s a thoughtless analysis — every day there are more new old people. For many groups the problem is an audience that has been irreversibly programmed into a torpor that extends well beyond their expiration date!”

Here’s my larger take, abridged and simplified for a blog response 🙂 —

An audience for classical music burgeons on the back of an emergent middle class. Such was the case in post-Enlightment Europe, late 19th/early 20th century U.S. and in Asia today. (I understand this is a hugely general statement which my provoke further discussion, but it is defensible.) However, for the majority of those newly middle-class music patrons, attendance and participation in classical music was an aspirational pastime — social elevation, aspirations for children, self-aggrandizement. How many in those audiences attended concerts or listened to radio shows to TRULY listen to the music?

Then, from about the 60s the musical monopoly began to fracture, in a big way. Rock & pop not only split the audience, but became the antithesis of the classical form — listeners had to pick a camp. One couldn’t listen to both.

Furthermore, if you would like to present a case study on exactly how NOT to brand a product take a look, a close look at classical music in the latter half of the 20th century until now. Really, who in their right mind would want to get involved with such a boring, dusty, self-congratulatory and self-involved product? You & I clearly understand the life-changing dynamism of this artform, but that certainly has not been its ‘brand”!

Even without the shoot-in-the-foot management of the music, one would expect the market to decline after the initial bubble of interest. That brings us to an interesting place however …

During a radio interview I made an off-the-cuff remark that provoked my thinking for a long time. I said something to the effect of, ” … my group has no great social stature, it’s not famous, so the only reason to come to our concerts is to listen to the music.” The more I thought about that, the more radical a concept it became to me … for historically that certainly has not been the case. With my chamber music audience, the ONLY reason they come to our concerts, is to listen to the music … and I mean REALLY listen … that’s stunning to me. What that also means is it is a very durable and loyal audience, returning high subscription rates from year to year.

Across the country and across the world this is an easily observable phenomenon — look at Mr. Sandow’s recent posts about “classical music clubbing”. It is primarily occurring with the more fleet, less expensive chamber music form — orchestras have a much more difficult adjustment to make — but this is what thrills me about where we are today. Yes, if you compare to mid-20th-century audiences the raw numbers are smaller, but what’s the count of the truly engaged?

As Mr. Sandow says, what we need is verifiable data, but I don’t see how that can reliably be collected — ticket sales to concert halls don’t portray a 21st century picture. How do we determine engagement via the myriad of contemporary delivery systems? How do we see the playlist on a person’s iPod — for the rock/classical antagonism no longer exists? Young listeners and performers are almost unaware of those boundaries.

History has value, and looking back to what was is of great interest. However, a comparison of musical performances in 1920 to 2020 (or 1913 & 2013) has the same value as a similar comparison between 1820 & 1920. One can’t compare — it is the classic apples & oranges situation.

My personal observations? I’ve been active in performance from the mid-1980s and with that comparison, my comparison, I see more creative, better engagement, more excitement. It’s a time of change for sure, and we will see the loss of edifices that we thought were too big to fail, at the same time though it’s the Classical Spring with grassroots activists, all around the world, wresting control of their artform for themselves. That future is today, and it’s not hard to find, and be inspired.

Thank you.

It seems to me that the one issue that really never gets discussed is the whole business of professionalizing the arts through academia in the first place. We might assume that the fact that Charles Ives couldn’t get a “professional” degree in music composition at Yale in 1898, was simply a sign of those backward times. Thank goodness that that’s all changed now, right? Now we can get B.M. degrees, M.M.s, D.M.A.s; what’s not to like? So what if artists are now supposed (required) to jump through the same kinds of hoops as doctors and lawyers: Boards of examiners, credentials, evaluations, etc.

Maybe we need to reexamine what happened to “classical” music and the creative arts in general when academic institutions took over the custodianship of our beloved music back early in the last century. Initially, colleges and universities knew that they had no business dealing with the creative arts except maybe through glee clubs and an orchestra. Sure, you could get degrees in theory, history, musicology, even eithnomusicology. But composition? And performance? Please! Artists can be messy people, and the old guard academics didn’t like messy. Composers and performers could go to conservatories, and painters and sculptors to academies. End of story…for then.

Of course, one of the first fruits of the newly-expanded academic composition departments was the juggernaut of twelve-tone music. Audiences were made to feel foolish for preferring a Brahms symphony over the latest howling, shrieking piece by Harvey Fartknocker, fresh out of Princeton. Even musically literate audiences could take only so much, and eventually, they voted with their feet.

To ignore all this, is to ignore all the subtle and even subliminal messages given by successive generations of parents to their children, resulting in a changed perception of what Adorno’s Culture Industry called “Classical Music.” Even if “Hey, come on, we’re not doing that anymore,” Humpty-Dumpty cannot be put back together. Sold out halls are great, but this music will never be a significant part of our culture again.

Trying to fix the problem of classical music without looking at this is like trying to fix the problem of “college is the new high school” by offering parents assistance in figuring out how to pay the five and six figure bills for their kids’ entry-level credentials. In both cases, I think we’re missing the real problem: The snow job by corporate academia on everyone.

Mr. Hardy makes some good points. But it’s also worth noting that the academy’s claiming of classical music (especially the composition of new classical music) was hardly a hostile takeover. Why was the “real world” so content to cede the glorious tradition of a cherished cultural tradition to a bunch of egg-heads bent on upending it? That’s what I’d like to know.