[From Greg: Introducing another guest blogger, Sally Whitwell, a pianist — and much, much more — from Australia. Her website says she’s a pianist, composer, conductor, and educator. But she’s still more than all of that. An exciting spirit, an innovator, one of the many people who’s reinventing what it means to be a classical performer. While teaching music to kids, with the greatest enthusiasm. I met her when she took one of my branding workshops, in which we had fun strategizing how she should present her portfolio career(s). With great results that she kindly credits to me, but which I credit 100% to her. I could say much, more more about her, but I’ll let her speak for herself, in this post, and future ones. I’m happy to have her here.]

When exactly did classical performers stop being that — i.e. performers? This is a question I’ve been asking myself for some time now. I can’t count how many classical musicians I’ve seen shuffle, wander, or slouch onto stage in an uninspired fashion. Either that or be so tense and uptight and wrapped up in the traditions (or habits) of classical concert etiquette that they stop looking human at all.

At the other end of the scale, there are performers who are beginning to see the value in performing in a rather more informal way, more like pop musicians playing a gig. They include a little chat in their concerts, talking about the music and what it means to them. I perform this way quite often myself and find that audiences are very responsive. They smile more and most seem to come up after the concert to converse with me about the music, and other things too. Maybe that’s just because at the end of those concerts I make a special effort to invite them to share a drink? Probably!

We’re even starting to hear the big opera companies and symphony orchestras talking the talk about ‘informalising’ concerts, which is meeting with various levels of success. There’s English National Opera’s Undress for the Opera initiative, encouraging the young folk to attend in jeans and sneakers. And then there’s Classical Revolution going the classical-music-in-pubs-and-clubs route. This is all well and good. Yes, it serves to make the music “accessible” and “relevant” and any number of other predictable-but-dry descriptors, but as you can probably guess, to me even this kind of talk is becoming just a little clichéd now.

Perhaps it’s already time to up the proverbial ante?

As a way to navigate my own way through to a braver and newer world of classical music performance, I’ve created a new performance genre for myself. With the kind support (and encouragement) of Marshall McGuire from Arts Centre Melbourne, I put together an all-playing-all-singing-dancing-acting-cabaret-piano-recital Ten Tiny Dancers which premiered at The Famous Spiegeltent, a cabaret circus tent on the side of the road in downtown Melbourne. Not your average classical concert venue I concede, but hey, this ain’t no average classical concert! My belief is that by recontextualising classical music, moreover by framing the abstract sounds of instrumental music by giving it a uniquely personal narrative structure, I can invite audiences to listen with fresh ears. Over the course of many years in the performing arts, I’ve picked up enough skills in playing, dancing, singing, acting and writing to be able to put together such a show.

***

The presenter’s brief for the event was this: I was asked to be part of something called Once Upon a Time, a series of performances by classical musicians where they tell stories about their lives, illustrated musically. I decided to tell a story from my teens, about having to make the choice between ballet (being a fairy princess and always giving some poor bloke a face full of tutu) or music (creating abstract shapes in sound, floating by in ephemeral mystery).

Now in my mind there was no way I could tell this story without actually dancing, so I enlisted a choreographer friend Brett Morgan to help me. The whole world of ballet dancing is also very stylised and incredibly magical and I wanted to reflect my own genuine affection for that not only within my own movement language, but also within the physical world that I inhabit on stage. Enter artist Pamela Lee Brenner who created said magic with a bunch of reclaimed and repurposed objects, plastic bottles, electric fans, flowerpots, a cat bed, acrylic fingernails, Barbie dolls, plastic shopping bags, milk crates and astroturf.

Pamela set about constructing from these disparate elements a magical garden, a kind of externalisation of my own imagination. Into this magical garden, I placed all the toy instruments I play, a sound world representing a distant childhood fantasy of sorts. I wrote a similarly stylised text for myself to speak/act. I chose a program of works by classical composers Prokoviev, Tchaikovsky, Debussy, and Satie, and contemporary composers Philip Glass, Andrew Ford, and Joseph Twist plus a few pop artists — Blondie, Kate Bush, Elton John — and wove them together in a way that would illustrate my story. Eclectic? I like to call it “La musique sans frontiers.”

The audience response was fantastic, I was so pleased. They were moved (“You made me weep”), impressed (“brilliantly crafted and performed”) and amused (“Loved your minimalist ballet fatality!”). The thing that struck me was that the audience responses were initially all about my story, not about the music per se. People talked about “That severe ballet mistress of yours, Sally, goodness!” or “I get so frustrated by dancers who can’t count, too!”

They couldn’t name the piece of music off the top of their head, because the show brought them rather too completely in my world and not into the composer’s world. You might think this is a bad thing for classical music. In the end, however, it worked out rather well. A number of them felt driven enough to get on my website and find out the details of the music from the part of my story they felt most keenly, and then seek out more of that composer’s work. They also, rather unexpectedly, felt compelled to tell me about their discovery even weeks after the show! If getting people enthused about classical music was the name of the game, then in a roundabout kind of way I really think I achieved that.

Of course, this kind of performance is not something every classical musician is going to want to do and neither should they. We all need to forge our own paths through this world. I would, however, like to encourage my classical musician colleagues to step back from what they’re currently doing, look at all the skills they possess as individuals and think about how they might use said skills to really communicate their passion for their artform. I found my pathway. What’s yours?

Antipodean creative Sally Whitwell is a pianist, composer, conductor and educator whose primary purpose is to Keep Classical Music Friendly. She’s equally happy performing solo recitals on concert platforms as she is playing rhythmic clapping games with rooms full of eight year olds. She and her partner Glennda live happily behind their shopfront studio in Sydney’s Inner West with their four fabulous felines Gandalf, Boudica, Lucky and Dickens. She enjoys cooking, walking and subversive cross stitch. Want more? http://sillywhatwell.weebly.

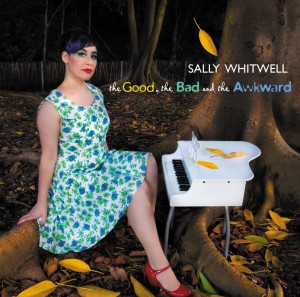

[Final word from Greg: Among much else, Sally has a fabulous visual sense. As gloriously shown, for instance, by the covers of her two CDs, which you’ll see below.. On the first, Mad Rush, she plays Philip Glass’s piano music. On the second, The Good, the Bad, and the Awkward, she plays a stunning selection of film music, including classical pieces that have been used in films. Twin Peaks (I loved that score, when the show was on), meet Haydn (by way of Interview with the Vampire).

[I should have included these in my post about CD covers I like. How could I have forgotten?]

Intriguing. Is there video of this performance?

Hullo! There’s some archival footage, but not really something of a quality that I can put up online… Yet. This is certainly not the last time I’ll be performing the show. Stay tuned!!

Thanks, Sally, well written. I am in violent agreement with your opening paragraph.

And the Once Upon a Time performance in The Famous Spiegeltent was indeed wonderful.

Thanks Ken 🙂 “violent agreement”? Really? I am taking this as a great compliment!

I’ve had a recent experience of playing with a large, mainstream orchestra which brought me to a somewhat disturbing realisation. It’s easy to fall into *their* way of performing i.e. without any commitment to occasion or stagemanship. I am proud to say that I didn’t give in to it though. There were people all around me standing awkwardly and unsmilingly waiting for the curtain calls to finish, some were even having conversations, doing their little concert post-mortems on stage! It was really quite disturbing. But thro it all, I just stood and smiled and tried to say “thank you so much” with my eyes. Afterwards, I left the hall with some of my colleagues and as we walked people came up and congratulated ME on the performance, ignoring my colleagues with their instrument cases. Was it because I actually looked like I was enjoying myself? Was it that they recognised my pink hair? Who knows. All I know is that a couple of my colleagues were put out. They teased me about it “Ha! You don’t even have a proper JOB with us” they mocked. Maybe not, but I’m the one they remembered so who’s laughing now 😉

That’s a very telling story, Sal. Not surprising, I fear.

As a friend and neighbour of Sally I can affirm that she has redefined what it means to be a classically trained musician. It is not crossover or even cross genre. Rather she brings her training and her practice with her and transforms it for her audience in a very stylish manner.

On the other hand, I saw Philippe Jaroussky the other evening in a more traditional setting. He spoke a little, but when he sang every sinew of his body performed. Performance can be multi-facited. John O’Brien.

Thanks John 🙂 I appreciate your support, ever so much!

It’s interesting that you talk about Jaroussky. I have seen him live in performance too and always admire his passion, his technique and the impressive physicality of his performing. Whilst traditional performance is just great, it really do feel it is preaching to the converted and it makes me wonder – for how long will there be an audience to sustain it? The world is changing around us and we need to communicate with that changing world.

Very, very good point. There are mainstream classical musicians who transform the idea of performance, simply by their presence and their inner force. Our goal, I think, shouldn’t be to change classical performance entirely, and (such a terrible thought) eliminate the old ways. Rather we should want to expand what classical performers are able to do. Which Sally has done.

Thank you Greg! I think that a balance between ways of performing could be struck somehow, kind of like Monteverdi working in ‘stile antico’ and ‘stile moderno’ simultaneously. Maybe the way I perform will attract a different audience? Maybe some of it will overlap with trad classical audiences, or with theatre audiences or cabaret audiences… who knows? At the moment, I’m just experimenting with performing as myself and this show was much more ‘me’ than I think I’ve ever been on any stage.

To quote an old Jewish expression (I remember my grandmother using it, though I’m sure it’s found in many places): “As long as you’re happy!” And you clearly are.

Your last point is something we all should embrace. It’s best not to worry about the exact nature of the audience we attract, when we’re performing from our hearts. The future will sort a lot of this out. Not that, if you’re a marketer, you shouldn’t ask yourself who’s coming, whether enough people are coming to make something affordable (which doesn’t mean it has to break even; just as long as it’s making whatever reasonable or even small amount you budgeted it for). Or whether these people are the traditional audience, or a new one, or both…

As much as possible, we should dance forward, and see what happens.

This “being yourself” thing as a performer is really important to me. I had an interesting interchange with a colleague on this issue. His opinion was as follows;

“That’s the difference between classical and pop music – the latter is about the performer as much as the music. In classical music, it’s just about the music and the personality and identity (and celebrity) of the performer needs to take a backseat.”

This rather disturbed me. What’s so wrong with us classical muso types expressing our own identities or telling our own stories through a composer’s work? As I mentioned in this blog post, my way of performing did mean that the audience were very aware of my story first but then they came back to the music/composer in a roundabout kind of way and this I believe is a good thing. I’m pleased with my experiment.

Another non-musician friend pointed something out to me too. People who love Andre Rieu say “I love Andre Rieu”. What they don’t say is “I love the waltzes and polkas of Johann Strauss”. Can we meet these people halfway somewhere, perhaps?

“The music” exists only as an abstraction. A very concrete abstraction, so to speak, because it’s precisely notated. But still, it doesn’t sound until it’s played. And so what people hear is _always_ the performer. If it were possible to play only “the music,” with nothing of the performer mixed in, then all the top classical musicians would sound essentially alike. There would be, so to speak, a kind of absolute zero, a perfectly neutral performance in which we heard only “the music,” and all the top classical musicians would approach that.

But of course in real life we see nothing like that. The top performers differ from each other quite a bit, and if you go back in time, to past generations, they sounded very different from how they sound now. So where’s “the music”? Top classical musicians in fact disagree quite a bit about what the perfectly neutral performance — one that realized only the composer’s intentions, with no performer mixed in — would be like.

So the whole notion is, to speak bluntly, a little crazy. It has no basis in audible reality. So we should celebrate what performers bring, because (1) there’s no way to keep it out (2) without performers, the music would never be heard, and (3) audiences respond to performers first, because that’s in fact what they hear — what the performer is doing with the music.

All this should be obvious, really. We’ve dug ourselves a hole, in which obvious things no longer seem clear. We need to get out of that hole.

I love Sally Whitwell for what she does. I loved what she did before I came to know her. The combination of Sally and what she does at least double the pleasure!

Thank you so much, John O’Brien!!

Greg, I’ve never really considered that ‘neutrality’ in quite those terms before. Rather I’d thought of it more in terms of ‘tradition’ – maybe that’s why I never fit all that well into the symphony or opera worlds and had to forge my own path(s)? This could also be what attracts me to composition, because there’s no ‘definitive’ (how I loathe that term) performance of what I compose, only the experience and musicianship of the people who perform it. If a piece I compose is different every time, that’s a good thing. Sameness is dull!

You should try the kind of loop composing I just did! Where you sit with the musicians, and mix the loops live. I loved throwing new things at them — starting in performance in a place we never started in rehearsals, making up an ending totally new to them and me. A chance to make the piece different in every performance. I wonder if the group I worked with would make their software available to others. There might be other ways of doing the same thing, of course.

As the groovy young people say… “Snap!” I used a loop pedal in the show so that I could make a cacophony of childlike sounds to accompany my rendition of Kate Bush’s “The Red Shoes”. It was a great resource, not only because of the sound world I was able to create but that it freed me to step away from the instrument and move around the stage. Pianists need to be extra clever theatrically because our instrument is not portable, so the stompbox looper is now my second best friend, after the ol’ goanna (that’s Australian for “piano”).