Years ago, a dear friend, a violist, gave two solo recitals, with the same program. One of the pieces was John Cage’s Variations IV, in which the score is nothing but a sheet of plastic with some black dots on it. You’re asked to draw a map of your performing space, overlay the plastic on it, and everywhere a dot falls, do something. [As we’ll see, I didn’t remember this correctly! I’m largely right, but got some details wrong.]

Years ago, a dear friend, a violist, gave two solo recitals, with the same program. One of the pieces was John Cage’s Variations IV, in which the score is nothing but a sheet of plastic with some black dots on it. You’re asked to draw a map of your performing space, overlay the plastic on it, and everywhere a dot falls, do something. [As we’ll see, I didn’t remember this correctly! I’m largely right, but got some details wrong.]

Which makes this one of those Cage pieces — the famous silent piece is the best known — that many people still think are fraudulent. This isn’t music! This isn’t art! You just do anything you want. Or as my wife put it in her Washington Post piece on Cage (linked, when it came out, on ArtsJournal):

To many artists, he was one of the most inspiring figures of the 20th century. To some musicians, he is underrated: branded, unfairly, more important as a thinker than a composer. And to a large segment of the public, he’s a charlatan: a man who convinced some people that sitting onstage in silence for four minutes and 33 seconds could be construed as performing a work of music.

Back to my friend. The first time she played her recital program, she made Variations IV the intermission. Wherever a black dot fell on her map, she put noisemakers (toy instruments, for instance), and asked the audience to walk around and use them.

But she didn’t like the result. People were, she felt, just doing anything they wanted, creating a kind of amiable chaos that was out of keeping with what she wanted the recital to be. So she thought more, and, at her second concert, made Variations IV the opening. Wherever a dot fell on her map, she went and stood, one place after another, and read excerpts from books about string playing.

She liked how that felt. It helped her mobilize for the recital. Helped her get over stage fright. Helped her think, maybe just below consciousness, of some technical things she’d have to be careful of, in the rest of the program.

Which taught her (and me) a lot about Cage. The point, in a piece like this, isn’t to do just anything. It’s to do something real. What that might be will vary from person to person, but you know it when you see (or do) it. You know, as does your audience, whether you’ve taken the easy road or a harder one, where you find yourself more focused, more intent. It doesn’t matter whether Cage tells you this or not, or if he gives you any explicit directions about precisely what you should do. Your mission is clear.

I wrote about this, decades ago, in one of my columns for the Village Voice, headlined “The Cage Style“:

You can play every note of a Beethoven sonata just as the score indicates, and still not get the music right; style seems even more important in Cage, because when the notes themselves are chosen by random processes, or left to the performer, how they’re played matters much more than what they are.

Beethoven, in other words, has a style we associate with his music, and a Beethoven piece played without some form of that style won’t be right. Same with Cage, but in many of his pieces (some, of course, are notated) the style becomes far more important, because there isn’t anything else. That’s why a performance of the famous silent piece, 4’33”, can be lame, if the performer just sits there like a lump, and does something clumsy to mark the three movements the time is divided into. (A detail often forgotten, when we talk about this piece.) But 4’33” can also be radiant, if the performer finds a way, coming from within, to frame the silence, so she both leads us into it and gets out of our way.

Cage, of course, took his pieces very seriously. Which means (as I wrote) that

Cage’s writings and personal manner [more on that below[ are a guide to his style, and so are his scores, which are put together (as Hanslick said, perhaps grudgingly, of Wagner) with “truly beelike industry.”

The first violin part of Atlas Eclipticalis, for example (which is only one of the 15 instrumental parts Cage made for the piece), consists of 70 complex events that must have required hundreds of I Ching coin-tosses and star charts overlaid on music paper to work out. Violinists can play the notes in these events in any combination and in any order, but if they understand what they’re looking at should feel challenged to be as diligent as Cage as they decipher the intricate; precise notation to learn bow many notes can be long, how many can be short, bow many can be repeated, which are loud, which are soft, and how to time them to follow the conductor. They’re challenged too by the severe graphic charm of the part to play musically, but never obtrusively.

Some pieces are notated more or less conventionally, meaning that you’re told what notes to play. But the notes are chosen randomly, which — as I discovered when I heard Frances-Marie Uitti play Cage — imposes an almost transcendent discipline on a musician who understands what’s going on. Fran (I later got to know her) is a cellist, and before I wrote “The Cage Style” I heard her play Cage’s Etudes Boreales

with the heat of a high-tension wire and unfailing control and beauty of tone, a virtuoso feat in itself, but also — which is exactly what Cage wants — as if each note were a new creation entirely unconnected to anything that had come before.

Of course not many people can do this. Which is why performing Cage superbly is such a rare gift. And why Cage’s music is so challenging. At the very least, a musician doing Cage should visibly be listening, ready to be delighted or surprised by anything that happens, even in the works where notes to play are written out.

An example from Cage himself: during my Village Voice days, I watched him play at a fundraising concert, for the Kitchen, then the leading New York alternative music performing space. (“Alternative” is what we might call it now. Then we’d have said “downtown.”) He was one of four people performing. Philip Glass and Blue Gene Tyranny were two of the others; I can’t remember the fourth.

Cage sat in semidarkness for 20 minutes, blowing into a conch shell. The sounds were soft and exploratory. The audience of donors and prospective donors, I might guess, liked what the Kitchen did, but might not have been ready for some of the more severe pieces we all heard there.

But they seemed to sit in mesmerized silence for Cage. I’d guess this was because he was so focused, so intent, so curious, so plainly listening to everything he did, listening with as much interest (and as little sense of ownership) as anyone in the audience. Which meant, to repeat the word, that he was curious about what he was doing, genuinely so. He had no agenda, but made his sounds with great delight, interested in what might come next, with no thought that he should shape it consciously.

That’s the kind of attention his music needs. (And rewards.)

I met him a few times, and, each time, thought he was one of the most joyful people I’d ever seen. Once we sat next to each other on a flight from Syracuse to New York. We’d both been at Syracuse University, he giving a talk, me attending a performance of one of my operas. (The Richest Girl in the World Finds Happiness, a very not-Cageian one-act, Broadway-like comedy.)

On the plane, he asked if I’d like to play chess. I won, and he burst out laughing. “I’m not good at chess,” he said, “for the same reason that [as Schoenberg had so famously told him] I’m not good at harmony.” (His mind, i might guess, liked more to let things take their individual place, than to put them in any kind of logical order. Not a good approach to chess!)

But, like anyone else, he could be human, vulnerable. When I was writing about new music for the Village Voice, a piece of his was done on a double bill, in a fairly minor venue, somewhere the music world didn’t often go. I came to see the non-Cage half of the bill, a performance by a friend of mine. I wasn’t there as a critic. Cage saw me, and gave a thrilled, surprised smile. He thought, hoped, that I was there reviewing. I’ve felt bad, ever since (for more than two decades) that I hadn’t been.

And one last story, to show how powerful, how deeply potent his music can be, for anyone. Somehow, years ago, I got into a discussion of Cage in my Juilliard course on the future of classical music. He wasn’t part of the curriculum, and I don’t remember how we got on him. (But digressions are a crucial part of any healthy life.)

One student, a virtuoso pianist, thought Cage was nonsense. I patiently explained. Had no idea, at the time, if what I said made any impact.

But it did, for which I’ll credit Cage, not myself. The student told me a couple of weeks later that he’d gone off to study Cage on his own, and been completely convinced. And not only that. Cage, he said, helped him play Rachmaninoff.

Because, after all, we’re always playing Cage, even while we’re playing other music. Or when we aren’t playing music at all.

I’d said I’d talk in this post about the future of classical music, the four crucial things we should be doing. But it’s John Cage’s 100th birthday! I thought I’d honor him, and go on with my own agenda next week.

***

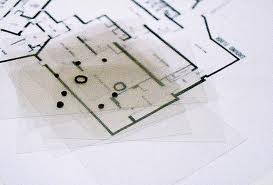

Here’s some commentary on Variations IV, from the online John Cage database. It’s worth reading for its own sake, but you’ll see what I got wrong in describing how the piece is played. I simplified its complexity. The moral in this, for journalists, bloggers, everyone: Always check your memory. We’re fallible. And the detailed truth is often more rewarding than the part our minds simplify and smooth.

Instrumentation: For any number of players, any sounds or combinations of sounds produced by any means, with or without other activities.

Duration: indeterminate

This is the second part of a group of three of which Atlas Eclipticalis is the first (representing ‘nirvana’, according to HideKazu Yoshida’s interpretations of Japanese Haiku poetry) and 0″00 is the third (representing ‘individual action’). Variations IV represents ‘samsara’, the turmoil of everyday life.

Like the earlier Variations the materials are transparencies (1 sheet with 9 points and 3 small circles) and a short written instruction. All points and circles are cut up and for the creation of a program 7 points and 2 circles are needed, which are all (except for one circle, which is placed anywhere on the map) to be dropped on a map of the performance space, creating places where actions might be performed. Lines are drawn from the placed circle to the points. The second circle is only used if one of the lines intersects it (or is tangent to it). The result is a graphic representation of where sounds may arise. Cage indicates that sounds may be produced inside and outside the performance space. There are no indications of durations, dynamics etc.

4’33” problem is what it reminds people of in the real world, which includes:

1) Admins who do nothing but don’t have a problem taking credit for the work of the performer

2) Bureaucratic excess (rules for its own sake)

3) Patent trolling, i.e. copyrighting a inane concept like silence

4) Completely devoid of meaning

Unless these issues are addressed directly, I don’t really see it gaining much support by the public or future generations, at least from an artistic/historical point of view.

But he was a marketing genius, though — he sold people nothing and got them to like it. Goes to show that you shouldn’t underestimate the power of a good story.

Depends on which people you’re talking about!

Yeah it depends, but I’d wager that the public, in general, will tend toward a negative interpretation of the piece.

What about the stifling of free speech? Having to sit in silence can be an oppressive experience for many. The list goes on and on.

Either way, I would try to find out the truth of what your audience thinks of your programming instead of relying on assumptions. It could work for some ensembles, but not for others. It just depends what you’re trying to sell.

Thanks for this, Greg. And I think you ARE writing about crucial things we should be doing for the future of classical music. That quality of engaged listening-while-performing is surely one of the most crucial, no matter what kind of music.

Thanks, John. And good to hear from you! Hope you’re thriving.

I love your thought here. Shows how making classical music more contemporary can refresh/renew performances of the old repertoire, too.

Your first hand stories of Cage the man are so enlightening and inspiring…wish I had been able to see him perform live as well! Coincidentally, from my (much more limited) POV:

http://martinperrypiano.blogspot.com/2012/09/john-cage-et-alia-redux.html

Thanks, Martin. And I like your blog post. Trying to do your part, and acknowledging how difficult that can be.

My wife’s piece in the Washington Post made a good point — that at least in DC, the Cage anniversary is being celebrated in art museums, and not for the most part by classical music institutions, including — very notably — the Kennedy Center.

Yes, the utter silence from the classical establishment is deafening.

At least someone could celebrate the prepared piano pieces, they are quite accessable and had a great impact on me.

Cage was just another composer with no talent for composition perpetrating his fraud on a gullible american musical intelligencia. His real ability was in selling this con to a bankrupt american culture starved for anything new for its own sake, however rediculous.

What works of his have you listened to?